Beethoven was none too sure about his only opera, Fidelio. When librettist Friedrich Treitschke set about revising the first versions of the opera, originally titled Leonore, oder Der Triumph der ehelichen Liebe (Leonore, or the triumph of marital love), Beethoven wrote to Treitschke, in March 1814, praising him for salvaging ‘a few good bits of a ship that was wrecked and stranded’ and thus inspiring the composer to ‘rebuild the desolate ruins of an old castle’. Just one month later, he was declaring his anxieties once more, describing the work as ‘scattered in all directions’. Wishing that he could compose something new rather than patch up the old, he concluded, ‘In short, I assure you, my dear T[reitschke], that this opera will win for me a martyr’s crown.’

The composer’s own uncertainties have led to two centuries of musicological debate about the relative merits of the different versions of what became Fidelio, and endless directorial experimentation with the opera’s many knotty issues – such as the imbalance and dramatic incongruity of the two acts, and how to fuse the seriousness of the subject matter with a singspiel form designed for light entertainment – specifically, what to do with the spoken dialogue? In this new production for Glyndebourne – first mooted in 2016, scheduled for the 2020 festival, postponed because of the pandemic, and now arriving at the House to open the 2021 Tour (though not actually one of the season’s three touring productions) – director Frederic Wake-Walker presents his own efforts to save Beethoven’s opera from its dramatic and generic flaws and to reveal its musical magnificence. Thanks to a terrific cast, several making their Glyndebourne debuts, and conductor Ben Glassberg’s fine appreciation of the ‘symphonic’ greatness of Beethoven’s score, this ‘rescue mission’ more than succeeds in the latter aim, but, dramatically, Wake-Walker’s visual and narrative interventions too often remind one of Beethoven’s ‘sinking ship’ metaphor.

In order to plug what he describes as the ‘many holes in the backstory’, Wake-Walker has excised the ‘clunky’ spoken dialogue, written a new spoken text in collaboration with Peter Cant and Gertrude Thoma, and created a new character, Estella (performed by Thoma) – a school teacher turned political activist and co-founder of an underground organisation, Prometheus, which aims to bring down Pizzaro’s oppressive regime. ‘Nelson Mandela could have written the mission statement’, Wake-Walker explained in a recent interview. A ‘sister’ of Orwell’s Winston Smith, in seeking to fight back against telescreen surveillance and totalitarian brutality, Estella reflects not upon doctored news reports from the Ministry of Truth, but pours over a letter from Leonore to Florestan, written prior to her rescue mission – a letter which has at its heart a poem written specially for the production by Zoë Palmer. Winston has his diary, Estella her laptop. Seated front stage-right, in Act 1 she guides us through the action, a Brechtian narrator distancing us from the events on stage. She shares Winston’s fate, however, trampled upon by a stampede of iron-shod boots and truncheons, and dragged off to prison where, beaten but not broken, she encourages Leonore in her mission.

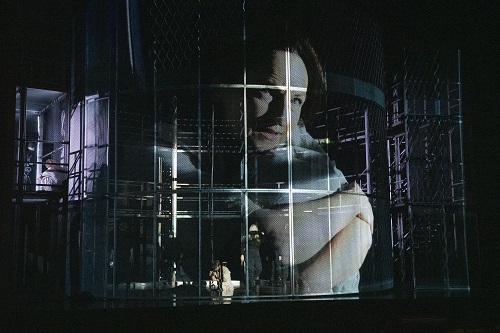

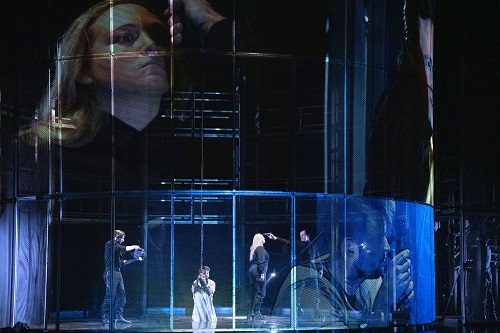

Designer Anna Jones’ prison is a panopticon – though probably not of the sort imagined by the eighteenth-century philosopher and social theorist Jeremy Bentham in his vision of the sort of constant surveillance that would reform morals and preserve health. Instead, Jones’ constructs a Foucaultian ‘cruel, ingenious cage’, a tiered, metal-mesh circle which occupies almost the entirety of the stage. In Act 1 it’s lit in shades of grey by lighting Designer Peter Mumford, then flooded with the glare of the golden sun in Act 2, and it serves as a cine-screen for Adam Fray’s video projects which present the action ‘in the round’, offering the audience multi-perspectives and aerial views, outsize close-ups of the events that are semi-concealed within the prison walls. It’s an impressive sight, but in practical terms it’s too often a hinderance, at least in Act 1 where the set occludes both the audience’s sightlines and, more importantly, the singers’ voices. Perhaps this is part of the reason, and not just first-night teething issues, that the stage-pit synchronicity was at times less than perfect, with the singers – in both arias and ensembles – struggling to keep up with Glassberg’s appropriately spirited beat.

Wake-Walker’s intention seems to be that the metal grille through which the stage action is half-espied should distance audiences from the protagonists, while the video projections serve to reconnect. At times, a hyperbolic enlargement, or a revealing angle, or an unflinching encounter with a character’s direct stare enhances the emotional intensity of a given moment. But, the montages of juxtaposed faces and perspectives during the ensembles often bring together, and overlay, personae who are in fact isolated within their own emotional experiences, hopes and fears. Elsewhere there’s simply a surfeit of visual suggestion, the images flickering in a kinetic visual display which is distracting and destabilising, deflecting attention from the music itself. It’s difficult to know where one should direct one’s gaze. And, pity the poor punter who doesn’t know the plot and needs to read the surtitles too – “If only I knew what was going on …” reads an unintentionally ironic title at the close of Act 1.

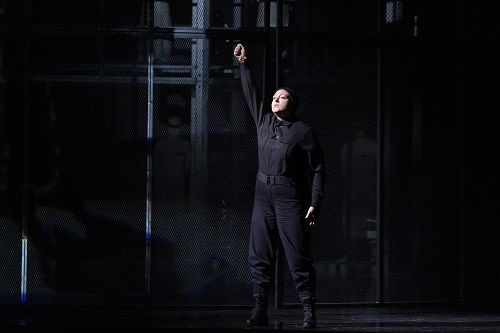

The characters, good and bad, are dressed in black uniformity, as hostile figures move among them operating hand-held cameras. It’s like being back at the National Theatre in the 1990s – I half expected a helicopter to arrive on stage. The prisoners’ chorus is shrouded in shadow, the white-smocked inmates’ brief moment in the light denied them. Their removal of their black eye-masks seemed more a gesture of disillusionment than of hope.

The music projects most clearly when the characters step beyond the cage-bars and sing from the forestage: if the narrow strip allows for little more than ‘stand and sing’ delivery, then at least we can enjoy, and be moved or uplifted by, these human voices and the feelings they convey. The panopticon walls are less intrusive in Act 2, pulled back to open up the stage, yet the interpretative overload continues, with freeze-frames, time-loop replays, and a fragmentation of the dramatic progression towards liberation. Don Fernando’s trumpets are heard, and the auditorium is bathed in light as voices from the heights sing promises of redemption; Leonore and Florestan, re-united, sing of their love and joy in ‘O namenlose Freude’ while barely acknowledging each other; Estella makes a reappearance. The trumpet call should have brought release and promised a new dawn, but when Don Fernando does eventually arrive, it feels rather an anti-climax – even though hyperbolic swathes of gold lamé are draped over everything and everyone, bathing all in hypothetical sunlight and liberty.

Thank goodness for the terrific singing and musicianship. Both German soprano Dorothea Herbert and English tenor Adam Smith are making House debuts and do so with impressive vocal composure and emotional impact. When Herbert stands alone in front of the prison walls and began to sing ‘Komm Hoffnung’, for the first time in the evening the audience are united in their focus – drawn into Fidelio’s conviction that she can rescue her husband. Herbert’s beautiful, shining soprano is captivating, and that beauty is allied with strength which sees her rise to the top of Beethoven’s sometimes discomforting vocal lines with flexibility and ease.

Smith is asked to sing ‘Gott! Welch Dunkel hier!’ on his knees, his hand-cuffed arms tugged this way and that by the rope that descends from the flies, and which denies him rest, but any physical discomforts did not impede Smith’s incredible lyric power and the vocal peaks blazed and burned with full-bodied richness as Florestan overcomes his knowledge of death’s approach as imagines his future life, transfigured in paradise. Despite the ravages inflicted upon Florestan, the youthful vigour of Smith’s tenor outshines the lingering presence of mortality. Also making his Glyndebourne debut is Dingle Yandell, whose stentorian bass-baritone conveys Don Pizarro’s biting, self-consuming viciousness in ‘Ha! welch’ ein Augenblick’, as he anticipates his revenge and confirms Yandell’s compelling stage presence.

The opening numbers struggle to establish a buffa lightness within the prevailing dystopian gloom, but Carrie-Ann Williams’ bright, fresh soprano captures Marzelline’s youthful passion in ‘O wär’ ich schon mit dir vereint’, and her faith in her fantasised future union with Fidelio. In contrast, Gavan Ring convincingly conveys Jaquino’s sense of defeat and uses his strong tenor well to create a compelling characterisation. Bass Callum Thorpe is a sonorous Rocco, though his ‘gold aria’ is deprived of some of its wry levity here, and Jonathan Lemalu an elegant Don Fernando. The Glyndebourne Chorus are superb – Robert Lewis and Thomas Mole stepping forward persuasively, as the First and Second Prisoners – and Glassberg urges his instrumentalists to find the lyric pathos and rhythmic punch of Beethoven’s score with equal impact. At the close the spirit of the Ninth Symphony seems re-born.

So many of the arias in Fidelio express hope for and belief in an imagined future. The present is ugly, but the social, political and cultural order – even the musical one, perhaps – can be overcome and the world transformed (only so far, though: Don Fernando is the King’s emissary, after all). Wake-Walker does indeed take us into a dark interregnum but the crisis that he creates is so burdened with ‘ideas’ that the new struggles to be born. The characters, lost within the panopticon’s twilight zone or disembodied in projected images, seem to speak only to themselves; hopes and dreams are not shared. Only in the closing moments, when a blanket of shimmering gold draws all into a collective body, and arms reach out to the audience, embracing us too, does the brotherhood of man seem faintly possible.

Claire Seymour

Estella – Gertrude Thoma, Jaquino – Gavan Ring, Marzelline – Carrie-Ann Williams, Rocco – Callum Thorpe, Leonore – Dorothea Herbert, Don Pizarro – Dingle Yandell, First Prisoner – Robert Lewis*+, Second Prisoner – Tom Mole*+, Florestan – Adam Smith, Don Fernando – Jonathan Lemalu, Actors (James Bellorini, Trevor Goldstein, Bella Harrison, Rachel Partington, Addis Williams); Director – Frederic Wake-Walker, Conductor – Ben Glassberg, Designer – Anna Jones, Lighting Designer – Peter Mumford, Projection Designer – Adam Young/FRAY Studio, The Glyndebourne Chorus (Chorus Director, Aidan Oliver), The Glyndebourne Tour Orchestra (Leader, Richard Milone)

* Soloist from The Glyndebourne Chorus

+ Jerwood Young Artist 2021

Glyndebourne, East Sussex; Friday 8th October 2021.

ABOVE: Fidelio at Glyndebourne (c) Richard Hubert Smith