The critics condemned the ‘entertainment’ as a ridiculous hoax. Noel Coward stormed out. After the show, one disgruntled elderly lady was rumoured to be lying in wait for the ‘soloist’ in order to smite her with an umbrella.

The first public performance of William Walton’s Façade – as recounted by the eccentric Sitwell siblings, Osbert, Edith and Sacheverell, within whose avant-garde literary milieu both work and performance were conceived – may have become infamous, but while contemporary reviews confirm that the audience reception was hostile, they suggest that in fact the performance was met with indifference rather than the violence that the Sitwell trio subsequently recalled. The day after the premiere the Daily Graphic headline read ‘Drivel they paid to hear’, while the pianist Angus Morrison’s memory was that ‘[e]veryone was perfectly good-mannered’: ‘The hall wasn’t very full, and the whole thing fell distinctly flat.’ No doubt it suited the Sitwells to be cast as artistic outsiders and for their divertissement to be classed a succès de scandale, Osbert later writing, ‘we had created a first-rate scandal in literature and music’.

This new release by SOMM Recordings, Sir William Walton: A Centenary Celebration, commemorates the 100th anniversary of the first private performance of Walton’s ‘musical entertainment, on 24th January 1922 and the 600th anniversary of the death of the Plantagenet monarch, Henry V, in 1422. In the former, baritone Roderick Williams and mezzo-soprano and actor Tamsin Dalley dance and dash through Edith Sitwell’s phonological tongue-twisters, racing rhythmic patterns and curious conceits, while actor Kevin Whately – known for his roles in television series such as Auf Wiedersehen, Pet and Inspector Morse – is the Narrator in the Orchestra of The Swan’s performance of the composer’s score for Laurence Olivier’s 1944 film of Shakespeare’s Henry V, conducted by the Royal Shakespeare Company’s Head of Music, Bruce O’Neil.

Façade has a labyrinthine history. It was first performed in the Sitwell brothers’ Carlyle Square drawing-room, with Edith reciting the poems that were accompanied by Walton’s hastily composed score for flute (doubling piccolo), clarinet (doubling bass clarinet), alto saxophone, trumpet, percussion, and cello. One month later, Sitwell published a limited edition of her Façade poems, and on the afternoon of 12th June the following year the first public performance took place in London’s Aeolian Hall, advertised as ‘A New and Original Musical Entertainment’.

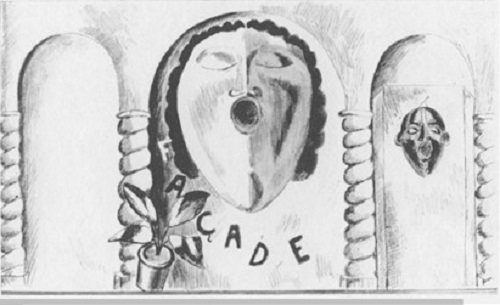

Sitwell and the musicians sat behind a transparent curtain on which the artist Frank Dobson had painted a large female face with African features and a smaller mask of a man’s face which the writer and aesthete Harold Acton described (in an account of another early performance) as ‘a blackamoor’ – the imagery mirroring the racial ventriloquism which is found in some of the poems. Edith recited her poems through a Sengerphone – a megaphone made of compressed cotton, which had been invented by opera singer George Senger – each poem being announced by Osbert who acted as impresario. The audience reaction was antagonistic: they had attended to be seen and had expected to be amused; instead, they had heard ostentatious and unintelligible gibberish. Osbert later wrote that for weeks afterwards, ‘When we entered a room, there would fall a sudden, unpleasing hush. Even friends avoided catching one’s eye, and if the very word facade was breathed, there would ensue a stampede for other subjects.’

The second public performance in the Chenil Galleries (1926) proved more successful, though the work’s detractors weren’t entirely silenced. Coward’s London Calling revue contained a skit titled ‘The Swiss Family Whittlebot’, a snide allusion to Johann David Wyss’s castaway novel The Swiss Family Robinson, prompted, Coward drily remarked, because the Swiss Jodelling Song – which quotes Rossini’s William Tell overture – was Façade’s only recognisable tune. In 1929, Decca recorded Façade with Sitwell reciting four and Constant Lambert seven of the then eleven numbers.

Walton made various arrangements, orchestrating four numbers for Diaghilev’s Ballet Russes in 1926 and producing an orchestral suite in 1938. It wasn’t until 1942 that the definitive 21-number version was heard, again at London’s Aeolian Hall, with the composer conducting and Lambert reciting, forming the second half of a concert which began with Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire. Walton returned to Façade in 1976, re-working eight numbers for reciter Richard Baker, and these became Façade 2: A Further Entertainment, which was dedicated to the American mezzo-soprano Cathy Berberian and first performed by Peter Pears at Aldeburgh in 1979.

A carnivalesque comédie humaine, Façade satirises prim Victorian mores and manners which are juxtaposed with hedonistic displays of frivolous pleasure-seeking – the absurdity of the age’s puritanical propriety being exposed and mocked in language characterised by equally absurd images – ‘swan-bosomed tree’, ‘foam-bell of ermine’ – and an auditory playfulness bordering on the nonsensical. Cultural allusions – high and low – abound. In the opening ‘Hornpipe’, the Laureate Lord Tennyson listens to Queen Victoria’s prudish complaints about a cortège in honour of a “shady lady”, the “new-arisen Madam Venus” who is as “hot as any hottentot”, a reference to the South African Sarah Bartman who was put on display as a freak show exhibit, ‘Hottentot Venus’, on account of her steatopygic body shape which h attracted both scientific and erotic interest – a characteristic act of nineteenth-century racial colonial exploitation. As golden bouquets are presented to Venus by the “fat and zebra’d emperor” of Zanzibar – the imagery seeming to both scorn and reinforce colonialist perceptions – Sir Bacchus and Théophile Gautier’s fictional Captain Fracasse gleefully glug “black tarr’d grapes’ blood” from the side-lines. Later it is Tennyson himself who is ridiculed, in ‘Sir Beelzebub’, in which the poet’s reflections on his own death in ‘Crossing the bar’ are reinterpreted as the Laureate’s progress across a hotel bar, “laid/ With cold vegetation from pale deputations/ Of temperance workers” who, moving in staid “classical metres”, try to “trip up the Laureate’s feet” as he approaches the rum-guzzling Beelzebub.

The setting of the poems is often ‘beside the seaside’, summoning images of the seaside entertainments – fairgrounds, pier shows, music hall variety acts – that the leisured classes and hoi polloi enjoyed alike. And, a large number of Façade’s poems bear titles connected to music – Tango-Pasodoblé, Valse, Tarantella, Country Dance, Polka, Lullaby and so on – indicative of the experimentalist poetics that Sitwell explained at length in the long Preface to Façade, in which she set out her intention to counter what she considered to be ‘the rhythmical flaccidity, the verbal deadness, the dull and expected patterns’ of contemporary Georgian verse, through rhythmic and sonic experimentation – manipulating speed, rhyme, assonance, dissonance, patterns – to create sounds and dynamism which are themselves the ‘meaning’.

Façade is often mentioned alongside Satie’s and Cocteau’s Parade and Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire, but the latter was not performed in Britain until 1923, and it is perhaps Stravinsky’s The Soldier’s Tale that is the closest musical bedfellow – certainly in terms of the instrumentation, the rhythmic innovation, the dalliance with jazz idioms, and the musical ‘borrowing’ from the past and from contemporary popular idioms which was so common during this period. Façade announces itself with a ‘Fanfare’ which here has a savvy swing in its step, the bright trumpet and trilling woodwind and cello bringing to mind a ringmaster marshalling his circus artistes before a buzzing crowd eager for the spectacle to be presented.

Sitwell’s ‘virtuoso studies’ in rhythmic sound-patterning present considerable challenges for the reciter, and both Roderick Williams and Tamsin Dalley acquit themselves with admirable oral dexterity and flair. Christopher Morley explains in his liner note that the texts have been allocated according to a scheme devised by O’Neil who has ‘ingeniously created within various settings what amounts to the internal dialogue of selected characters’. In the opening ‘Hornpipe’, the two voices frolic in turn around the snatches of ‘Rule Britannia’, in a perfectly synchronised dialogue, in a sense mimicking the interplay between the saxophone and trumpet. Both reciters use intonation, regional accent and emphasis to convey character, nuance and meaning, in ways which Sitwell is said to have eschewed, but they do so with, on the whole, good judgement. In ‘En Famille’, as the energy subsides into Debussy-like languor, Williams – who in the slower, more narratorial episodes sometimes can’t resist the instinct to ‘quasi-sing’ – embodies the patriarchal Admiral, posted in China, who is concerned that his daughters, Jemima, Jocasta, Dinah, and Deb – represented by Dalley – will succumb to the oriental allure of the East. This ‘characterisation’ does introduce a lively dramatic element into the numbers, but I’m not sure that Sitwell would have approved! And, to some extent it diverts the listener’s attention from the sound of the words themselves.

Similarly, in ‘Black Mrs Behemoth’ some of the ambiguity is lost by splitting the poetic voice between a distinct narrator and character, giving specificity to the woman’s rage, rather than letting the taut snare drum and ominous accents do the evocative labour. ‘By the Lake’ is more successful in this regard, the enunciation controlled and restrained, allowing the musical murmurings and the metrical regularity to convey the slightly sinister sadness of the imagery of passion’s demise: “Dead, the leaves that like asses’ ears/ hung on the trees … the hard cold bell-buds … codas/ Of overtones, ecstasies, grown for love’s shroud.”

Dalley particularly impresses in the ‘Tango-Pasodoblé’, slipping from a charming poise into a deliciously fluid rush of alliterative assonance in which the unintelligible becomes deceptively lucid, “Thetis wrote a treatise noting wheat/ is silver like the sea;/ the lovely cheat is sweet as foam;/ Erotis notices that she …”. She controls the syntax-evading linguistic structures consummately. And, she has great fun with the rattling rhymes and rollicking rhythms of the ‘Tarantella’, flying through the dense soundscape with ease and grace. Against the instrumental busyness of ‘Country Dance’, Williams articulates the sonic niceties of phrases such as “For strawberries bob,/ hob-nob with the pearls/ Of cream (like the curls of the diary girls)” with rectitude and relish; and, the baritone is masterly in the jaunty, jazzy ‘Popular Song’, so relaxed and even through the rapid-fire patter:

“Lily O’Grady,

Silly and shady,

Longing to be

A lazy lady,

Walked by the cupolas, gables in the

Lake’s Georgian stables,

In a fairy tale like the heat intense,

And the mist in the woods when across the fence

The children gathering strawberries

Are changed by the heat into Negresses.”

Coward would surely be impressed!

O’Neil expertly shapes both the contrasts between the numbers and the metrical transitions and accumulations within them. The sultry sway of ‘Long Steel Grass’ acquires an increasingly confident swish, culminating in Il Capitaneo’s imperious demand, “Come kiss me harder”. Colour and motif are equally lucid. In ‘Through Gilded Trellises’, woodwind curlicues sculpt images of the gracious flirtatious fan of Dolores, Inez, Mauccia, Isabel and Lucia, evoking too the coils of heat that spiral through the fragrant garden, as a castanet caresses the air. There are troubling shadows in the questioning, blues-tinted ‘Lullaby for Jumbo’, though the closing pianissimo cymbal shiver lifts the weight from the bass clarinet’s pathos. And, in ‘Four in the Morning’ the plangent moans of saxophone and the flute’s disturbed meandering effectively capture the fraught tone of Mr Belaker’s unanswered questions which are portentously pronounced by Williams. Moreover, the aristocratic exchanges of the Frenchified, elegant ‘Valse’ twirl, like the imagined dancers, with a subtle frisson of romantic expectation which is sharpened by the sonic excess – “The stars in their apiaries,/ Sylphs in their aviaries,/ Seeing them, spangle these/ and the sylphs fond/ From their aviaries fanned …” – phrases which are supported with lovely suppleness by a droopy instrumental lilt. When, finally, Sir Beelzebub calls for his “syllabub”, Williams and Dalley frolic in perfect tandem to the band’s brassy beat. It’s a confident conclusion to a persuasive reading of Façade.

Walton’s score to Laurence Olivier’s morale-boosting 1944 Technicolor film version of Henry V also starts with a fanfare, and it’s a punchy opening to the chamber version for eleven players – flute, oboe, two clarinets, bassoon, horn, trumpet, two cellos, percussion, piano and harpsichord – by Edward Watson that is presented here, conjuring the “swelling scene” amid which “warlike Harry”, purposeful, noble, mingles. In the Chorus episodes, Kevin Whately is an inviting, engaging narrator, and the balance between speaker and accompaniment is well-judged by the engineers, neither element too ‘forward’, both equally well-defined and crisp.

A jaunty bassoon conjures the light heads and hearts in the Boar’s Head, and prefaces Pistol’s shocked declaration, “Falstaff, he is sick,/ The king hath killed his heart”, that wrenches the mood into melancholy loneliness as Falstaff’s sincere prayers, “God save thy Grace, King Hal! My royal Hal!”, are met only with rejection and derision. Whately captures both the sense of a duty which drives Henry’s hardness of heart, and Pistol’s pragmatism, and both cast a poignant shadow over ‘Touch her soft lips and part’, which is beautifully played. Perhaps inevitably, it’s hard for the small ensemble to do justice to the more ‘spectacular’ cinematic episodes, but Whately’s speeches at Harfleur and when convincing his flagging troops that “The day is ours” do much to restore some of the passion and majesty that a full orchestral version would evoke. And, at the close, he sounds utterly bewitched by the French princess, Kate, with whom marriage will ensure that “never war advance/ His bleeding sword ‘twixt England and fair France”.

This disc reminds one that Walton in general, and Façade in particular, merit revisiting and re-evaluation. Music scholar Michael Kennedy has remarked that, ‘It is misleading to regard Façade as only a ‘false start’, frivolous and unrepresentative. It is unique and unrepeatable, as Walton wisely realized, but it contains the essence of him—even to the ‘conservatism’ which has earned him so much disrepute in advanced circles lately … most remarkable of all – in retrospect – is the work’s poetic vein of nostalgia which is not something that has been added by the passing of years’. I’m not sure that Façade is representative of the ‘essence’ of Walton, but it does have brilliantly ambiguous hybridity, which this new recording brings to the fore.

Christopher Morley’s well-informed liner note does not address the complicated relationship between the presentation of colonial and imperial perceptions and their subversion within Façade. But, the performance here of Walton’s ‘musical entertainment’ really illumines how, paradoxically, the work aligns itself with the ‘popular’ in order to confirm its own elitist erudition, while simultaneously mocking cultural and artistic prudishness. It is at once both familiar and strange, hovering on a knife-edge between sense and nonsense. And, it’s fabulous fun too.

Sir William Walton: A Centenary Celebration is released by SOMM Recordings on 21st January.

Claire Seymour

Roderick Williams, Tamsin Dalley, Kevin Whately (reciters), Bruce O’Neil (conductor), Orchestra of the Swan

Walton: Façade; Henry V (arr. Edward Watson)

SOMMCD 277 [80:56]