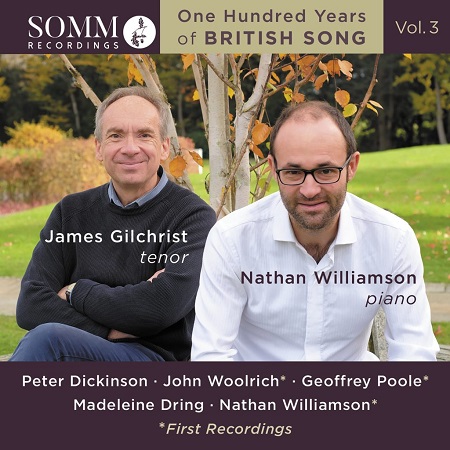

With this third and final instalment of their survey of 100 years of British song James Gilchrist and Nathan Williamson bring us up to the present day. Their focus is music composed since the late 1950s, and four of the five composers represented are still working today. In his engaging accompanying article, Williamson describes the repertoire presented on the disc as testifying to the ‘polyglottal musical diversity’ of the composers working within the Western classical tradition since the latter half of the twentieth century.

Peter Dickinson’s ‘Let the Florid Music Praise’ (1960) is an ostentatious programme-opener, Dickinson matching the arresting vocative of Auden’s ‘Song’ with an apparent homage to the thunderous tolling that opens Rachmaninov’s Second Piano Concerto. The vocal line is pushed high in the opening stanza, in which music praises beauty, and Gilchrist’s tenor glows firm and true through the challenging melismas, surging dynamically, the text clearly enunciated despite the challenging register. As in Britten’s setting, the sombre second stanza is more meditative, and Gilchrist’s tenor is softly reflective as the melody follows the natural rhythms of the text. A bristling flourish, however, ripples through Auden’s opaque final couplet, “And my vows break/ Before his look.”,and the reflective piano postlude highlights the contrast between the image of permanence – “Let the hot sun,/ Shine on, shine on.” – which closes the first stanza and the fateful transience which colours the close.

Dickinson’s Four W.H. Auden Songs were composed in 1956 when the composer was an undergraduate at Queen’s College Cambridge. There’s a Britten-esque quality to the vocal line, which is melodious, rhythmically vivid and natural. Gilchrist’s warm invitation, “Look, stranger, on this island now”, is dramatized by pictorial pianism, Williamson’s arpeggiac-arcs conjuring the “leaping light” and “The swaying sound of the sea”. Dickinson again responds to the progression of the text and as the immediacy of the island fades, and the viewer’s gaze is directed to the boundary between land and sea, “Where the chalk wall falls towards the foam”, so the music slips into musing, just as the island is embraced within the sauntering waters and passing clouds. Gilchrist directs us towards the distanced ocean horizon, “Far off”, with floating tenderness.

‘Eyes look in the well’ guides us to a more disturbing scene, and the duo exploit the small changes to the strophic repetitions to build from sober mood-setting, through emotive imagery – “The robbed heart begs for a bone,/ The damned rustle like leaves” sings Gilchrist, with heightened intensity – to terrible vision. Powerful declamatory rhetoric reveals the “One the soldiers took,/ And spoiled and threw away.”, the piano’s funereal postlude riven with violence and grief. I’m not sure if the folk-like simplicity of ‘Carry her over the water’ which, to echo the final line of each stanza, “Sing[s] agreeably, agreeably, agreeably of love”, is intended to parallel Auden’s mocking irony, but Gilchrist colours the text affectionately, as nature blesses the two beloveds, and Williamson’s light, roving animation of the final stanza evokes the blissful nuptial conclusion to the courtship. ‘What’s in your mind’ darts about playfully, jazzily, as the protagonist badgers the lover with dancing questions which build into sexual invitation and climax with an expression of ecstasy. There are beautiful songs, beautifully sung.

Madeleine Dring was a pianist, singer, composer and actress. She died suddenly from a brain aneurism aged 53, leaving many works unpublished, and her husband Roger Lord, principal oboist with the London Symphony Orchestra for over 30 years, worked tirelessly to promote his late wife’s work. The Five Betjeman Songs (1976), composed one year before Dring’s death, are musical embodiments of the late Poet Laureate’s vignettes of Britain and the Britten, each song stylistically unique. The dreamy lapping of wave on rock and shore suffuses ‘A Bay in Anglesey’: a delicate perpetual motion, occasionally stirred by upswells, above which the calm vocal melody floats, as the protagonist observes with wonder the bladderwrack at his feet, the lark song whispering through the salty scents, and the hazy vision of distant Snowdon which “rises in pearl-grey air”. There’s a timelessness about this song, as the duo evoke both the magic of the present scene and the mystery and melancholy of the island’s past.

‘Song of the Nightclub Proprietress’ is brilliantly done. Williamson resists the temptation to ham up the Gershwin-infused jazziness, and Gilchrist lightens his voice and adopts a crisp RP, perfectly capturing the register and rhythm of the female protagonist’s wistful reflections. The vocal shiver as the thick magenta curtains are “pulled aside” and the exaggeratedly rolled ‘r’, “So Regency, so Regency, my dear” are perfectly judged and delivered. As ever Betjeman balances humour and nostalgia through precise imagery, and it’s no surprise that Gilchrist relishes the textual subtleties, describing with crisp delectation the “Kummel” (a colourless liqueur), overflowing ashtrays and “squashed tomato sandwich” that litter the morning-scene, as spiders “race across the ciders”. But, Dring halts the blithe rhythmic roll in the final three lines, when the now-dying proprietress wonders, “What on earth was all the fun for?” Gilchrist and Williamson shift from blasé to bleak, burdening the disjointed words with a heavy finality, “I am ill and old and terrified and tight”, the final admission of inebriation a paradoxical quasi-sneer of self-disgust and defiance.

In ‘Business Girls’, Dring complements Betjeman’s masterful, and melancholy, evocation of time and place – lonely, single shopgirls get ready for work as life passes them by – with unassuming grace, capturing the contrast between the hustle-bustle of London life and the poignancy of the girls’ momentary morning stillness as they bathe before the day’s mundanities. It’s a tender but unsentimental portrait. Gilchrist was recently a mincing Reverend Adams in the ROH’s Peter Grimes; the zealous vicar of ‘Undenominational’ is rather more effectual, and the duo conjure the bellowing fervour which inspires “glory” in the soul of the converted. ‘Upper Lambourne’ is a lyrical portrait of English racing country, in which Betjeman uses rhyme and repetition to unify lines of varied length which are often interrupted by caesura. Dring employs a 5/8 meter which has both lilt and stutter, perfectly evoking a nostalgic glance back at the past achievements of the horse trainer who now lies beneath the nettle-strewn “stained Carrara headstone” in the shady vale. Williamson’s chordal accompaniment trips lightly and Gilchrist delivers the trickily-set text with exemplary precision and care for Dring’s craftsmanship.

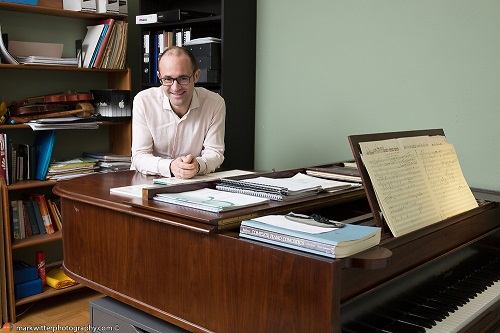

Williamson offers some of his own compositions, too. The Little That Was Once A Man sets poems by Bryan Heiser, whose family and friends commissioned the song-cycle shortly after his death. It was written in 2016 for Gilchrist and has since been substantially revised. Heiser’s poems are eclectic in subject, diverse in form and scale, and juxtapose the irreverent with the sobering, the playful with the passionate. Williamson explains that a basic trochaic rhythmic motif – based on the pronunciation of the poet’s name, Bry-an Hei-ser, serves as a ‘musical footprint’ through the cycle. These are incredibly difficult songs to sing, angular, wide-ranging, often only sparsely supported elsewhere overwhelmingly clangourous, requiring vastly contrasting colours, and juxtaposing forthright power and exquisite delicacy. Gilchrist more than meets the demands. ‘In someone else’s poem’ is both fragile and fierce. The melody elongates the texts and sends the voice high, often quietly so. Williamson’s setting and Gilchrist’s sustained high voice, “they are too sun-struck to lift/ a finger”, capture both the submerged anger and the irony of Heiser’s enjambment between verses. In ‘4.a.m.’ the stillness of the early morning, a softly whispered pulse, is violently overcome by the terrors of the nocturnal imagination, the piano’s thunderous explosions revealing the engulfing potential of the images within the subconscious.

Heiser’s ‘Not being …’ is subtitled ‘After John Heath-Stubbs’ Not being Oedipus’, alluding to Heath-Stubbs’ rendering of the Theban myth as a more ordinary story, stripped of its fated crimes and tragedies. The three movements obliquely improvise on Oedipean themes, from sexual violence to moral blindness, from misconception to hubris. Gilchrist negotiates the racing text, the skidding halts, and the extreme dramatic voices, some of which require unorthodox vocal techniques and sounds, with absolute assurance. The final song, ‘Moon at rest’, is more lyrical and settled, the steady piano pulse providing an anchor, though permitting some restlessness. It’s no less taxing vocally, though, with Gilchrist repeated asked to sustain lines at the top of his range, as the poet anticipates the day when his family will carry his ashes “to the compost bins/ and there … pour onto that gentler, nourishing fire/ the little that was once a man”. The expansion of the melodic compass here is richly Romantic, and as Gilchrist climbs ever higher through the final image, “where the long green grass snakes nest and sun”, to a thrilling head-voice pinnacle, there is transcendence.

John Woolrich’s The Unlit Suburbs (1998) setsthree poems by the Irish poet Matthew Sweeney which take the listener into liminal places between the real and the fantastic – what Sweeney called an ‘alternative realism’. ‘The Submerged Bar’, at barely one-minute, is the longest of the three songs. Its fragmented recitation, supported by piano stabs and splutters, has a strange rhythmic coherence which makes one believe in the time-denying speakeasy where it’s “best not to be found … during the hours of daylight”. Gilchrist imbues his tenor with ghostly shadows in ‘Rat Town’ though the song’s message is no less threatening for its understatement, while ‘The Ghost Choir’ is laconically macabre, the melody carefree, the piano a clatter of rattling skeletons.

The final group on the disc is Geoffrey Poole’s The Eye of the Blackbird (2014), which refashions settings of Wallace Stevens’ Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird from the composer’s oratorio, Blackbird (1993). The vignettes are brief and diverse of idiom. The high piano chords which etch the ‘Twenty snowy mountains’ are aloof, self-contained: “The only moving thing/ Was the eye of the blackbird.” In ‘I was of three minds’, the slow, careful enunciation of Gilchrist’s extending vocal phrases, “I was of three minds,/ Like a tree/ In which there are three blackbirds”, deepens the enigma, to which the piano’s busy, delicate after-commentaries provide no resolution. ‘The Autumn Wind’, with its spiky whirling, ‘Icicles’, with its glistening metallic crackles and plummeting booms, and ‘He rode over Connecticut’, with its lolloping gallop and vocal yelps, are more tactile and immediate. ‘I know noble accents’ is almost impudently insouciant, cocky rhythms accompanying Gilchrist’s confident assertions, “I know”. The circling patterns and resonant spaces of ‘Out of sight’ evoke metaphysical mysteries. Gilchrist and Williamson illuminate the way that Poole has captured the paradox of Stevens’ poems: that they are fecund in their multiplicity of possible perspectives but somehow intimate a unified vision.

Several of the song-groups, including those by Williamson himself, are premiere recordings and – in contrast to the songs recorded on the first two volumes of the series – there is a sense of looking forward, to the unknown directions that art song will take, rather than casting a wistful backwards glance. Indeed, Williamson concludes with the observation that the ‘enormous changes within music over the last 100 years leave me none the wiser as to what any song composed tomorrow will sound like – an incredibly enticing and inspiring thought’. In this spirit, to promote both the legacy and future of this body of work, Gilchrist and Williamson have founded a new organisation, The Art of British Song.

Claire Seymour

One Hundred Years of British Song Vol.3: James Gilchrist (tenor), Nathan Williamson (piano)

Peter Dickinson (b.1934) – ‘Let the Florid Music Praise’, Four W.H. Auden Songs; Madeleine Dring(1923-77) – Five Betjeman Songs; Nathan Williamson (b.1978) – The Little That Was Once A Man; John Woolrich (b.1954) – The Unlit Suburbs; Nathan Williamson – Intermezzo; Geoffrey Poole (b.1949) – The Eye of the Blackbird. SOMM CD 0646 [66:40]