Keith Warner’s Otello is a crucible of darkness and light. The minimalism of Warner’s conception and design seemed even more striking to me during the opening night of this second revival at Covent Garden than it did when the production was new, in 2017. Monochrome juxtaposition dominates from the first moments when Iago, alone on stage, viciously smashes a white Venetian mask to the ground while holding its black counterpart aloft as smoke-swirls of deception engulf him, to the closing image which pits Desdemona’s white-on-white bedroom against a split-level column of tragic blindness.

In Warner’s opening storm-scene, Iago’s smoke-screen merges with the mist and water that veil the General’s ebony galleon as it battles through the tempest off the Cypriot coast. The Cypriots sing of the ‘spirit wild of chaos’, black-browed and blind that cleaves the air. “All is smoke! All is fire!” they exclaim, “The dense and dreadful fog bursts into flame, and then subsides in greater gloom.” It’s a proclamation which in this production seems a metaphor for the whole emotional drama that is about to unfold. And, it’s a conceit which is also visually embodied by Warner’s presentation of Iago’s Credo within a smoky Hadean furnace embraced by existential blackness.

Symbolic white punctures and counters the expressionistic gloom. The winged Lion of St Mark’s on the galleon’s standard is welcomed by the Cypriots anxiously watching the ship’s prow-tossed progress through the rocks. And, the white beast takes statuesque form in Act 3, wheeled on before the white-suited Venetians whose cries of praise, “Evviva il Leon di San Marco!”, are undercut by Otello and Iago’s furtive plotting of the method of Desdemona’s murder – and by the flood of scarlet that bathes the stage in anticipation of the blood to be shed. It’s a dramatic gesture but one that felt no less clichéd here than it did in 2017, with the subsequent beheading of the Lion in Act 4 similarly superficial.

It is Desdemona, though, who truly brings light into the darkness, literally so in this production. When Bruno Poet shines a piercing spotlight on her white silk gown in the opening Act, the latter gleams like a beacon of innocence and goodness. Then, in Act 2, when Desdemona is serenaded by a chorus of children, the back of the stage smoothly opens up allowing in the warm Cypriot sun and subtle hints of verdure sweetness, emitting a Caravaggian ray which does not quite reach the forestage shadows in which Iago lurks. In the final Act, when Otello stabs himself the white purity of Desdemona’s bedchamber is marred with a splash of red blood, reminiscent of the strawberry-embroidered handkerchief that is a symbol of both their love and their tragedy.

The window slits and latticework of Boris Kudlička’s shape-shifting set hint at the Mediterranean locale but permit little brightness. As the angled walls and blocks close in the tension tightens and Poet’s magical sleights of illumination emphasise both the expressionistic external world and the conflicts within Otello’s psyche, as when white graffiti daubs on the ebony walls publicise Desdemona’s infidelity and mock the Moor’s masculinity – ‘Ecco il leone” – visually confirming the fracturing of his ‘self’.

Such minimalism requires both skilful movement of the collective personnel and a stellar trio of protagonists to restore the emotional sophistication of the drama. In 2017, I found some of the blocking rather static, but on this occasion there seemed a greater fluency and naturalism, the large ROH Chorus moving swiftly to the sides and rear to allow focus on the protagonists. If the movement is rather en bloc at times, then this is pragmatic and dramatically pithy if occasionally a little stylised. And, the fight which ensues when Roderigo follows Iago’s command to goad the inebriated Cassio is as graceful, and as detailed, as a dance.

There are some thoughtful placements, as when Cassio and Desdemona are framed within an illuminated trellis bower at the rear, watched at the front of the stage by Iago whose arioso-soliloquy, directed straight at the auditorium, seems to make the audience complicit in his cunning. In the quartet, when Emilia picks up the dropped handkerchief, Warner skilfully juxtaposes Iago’s coercive cajoling in the rear shadows with Desdemona’s declarations of submission, humility and love. And, Warner makes effective use of the edges of the stage, pairs huddled in intrigue or aggressive confrontation, as when Otello brands Desdemona a whore and pushes her against a wall, forcing himself upon her. As she limps and lurches from his grasp, Desdemona’s horror and despair are palpable.

Vocally and dramatically, it was the darkness that prevailed in this performance. Making his role debut as Iago, baritone Christopher Maltman gave a remarkable potent performance, communicating Iago’s evil with disturbing persuasiveness. Shakespeare’s Iago may tell Roderigo, ‘I am not what I am’, but this Iago truly does wear his heart upon his sleeve ‘[f]or daws to peck at’. His voice pumped with oozing blackness and almost psychotic self-belief, Maltman was a Machiavellian ‘smooth operator’ from the first, his suave energy driving the Act 1 drinking song and effortlessly, and nonchantly, turning carousing to conflict. The baritone’s vocal acting was superb. Details such as the pacing and colour of his guileful observation, ‘I like not that …’, which triggers Otello’s suspicion, and the floating head voice with which Cassio’s dream-drenched infelicities were falsely recalled – “Sweet Desdemona! Let us hide our loves. Let us be wary! I am quite bathed in heavenly ecstasy!” – and which dripped with deceit, revealed both Iago and his vocal creator as masterly, manipulative thespians.

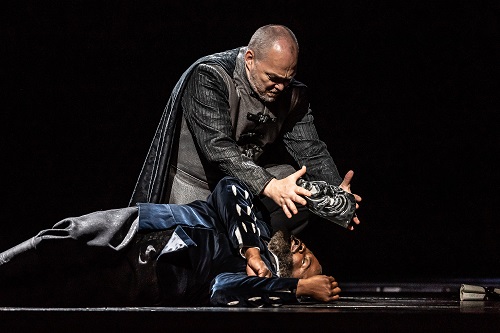

Standing behind the Otello whom his scheming lies have reduced to a crumpled knot of doubt and fear, this Iago looked unnervingly exultant, his face animated with pleasure at another’s pain, his hand raised in laudation of his own evil. Even when challenged by the rageful Otello in ‘Tu! Indietro! Fuggi’, his unflustered self-assurance remained undiminished. Moreover, the growing bond between Otello and Iago was convincingly shaped, making the moment in Act 3 when Iago smothers the prone Moor with his black mask all the more shocking, a horror which deepened when the masked Otello staggered before a mirror and recognised the ‘self’ within the frame – Shakespeare’s ‘malignant and [a] turban’d Turk’ who must be smote to resurrect the myth of the Moor of grandeur and greatness.

Maltman’s Credo was a hell-fuelled rejection of God, terrifying in its nihilistic rejection of death as “nothingness, heaven an old wives’ tale”. The brutal anger seemed to belie buried feelings. Something more than resentment of Cassio’s promotion, suspicion of Otello, misogyny, or even Coleridge’s ‘motiveless malignity’ seemed to fuel his wickedness. Some recognition, perhaps – although he declares man to be merely the ‘sport of evil fate from the germ of the cradle to the worm of the grave – of the absence of something essentially ‘human’ from own soul, just as Shakespeare’s Iago wishes to destroy Cassio because, ‘He hath a daily beauty in his life/ That makes me ugly’. In a letter to Boito, Verdi described Iago as ‘the Demon who moves everything’. Maltman was that ‘demon’ and this was a brilliant performance of astonishingly concentrated dramatic and vocal focus.

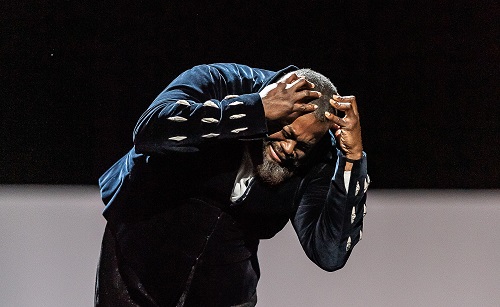

The American tenor Russell Thomas was the demon’s tragic dupe. That it seems necessary to note that this was the first time a black singer has been cast as Otello at the ROH is a disappointing reflection on the opera profession, past and present. This is the fourth time that Thomas has assumed the role, but he struggled to assert Otello’s authority in the opening scene, and while this may, to some extent, be because here the Moor emerges from within the crowd, somewhat submerged by their cries of victory, Otello’s clarion roar was a little subdued throughout, not always cutting through or riding above the impassioned orchestral drama.

What Thomas did possess was an unwavering lyricism which recalled Wilson Knight’s ‘Othello music’, a lyricism that conveyed Otello’s introspection and gullibility, and which Thomas pushed as far as he could to show the Moor’s psychological unravelling. Both the self-torturing ‘Dio! mi potevi’ and the grief-riven ‘Niun mi tema’ were beautifully sung, but the more explosive outbursts lacked the sort of power and nuance that make Otello’s journey from doubt to delirium credible. And, it did not help that Thomas is not a natural stage animal, his acting somewhat limited and wooden. Verdi may have remarked to Boito that ‘Otello is the one who acts: he loves, is jealous, kills and kills himself’, but this was a passive Otello: things were done to him. I remember vividly the moment, in 2017, when Jonas Kaufmann walked onto the short platform extending high above the ROH stage to over-hear Iago’s teasing trickery of Cassio – he was exposed, vulnerable, threatened by literal and psychological dangers. Here, Thomas was seated on the platform, to its rear; my guest for the evening scarcely noticed he was there.

As Desdemona, the Armenian soprano Hrachuhí Bassénz made a somewhat tentative start, seeming not entirely comfortable in the gentle lyricism of Act 1 as Desdemona and Otello narrate their tale of courtship. But, she grew in confidence and credibly communicated the strength of Desdemona’s love and her heartbreak at Otello’s hostile rejection. Bassénz was at her best in Acts 3 and 4. When the weeping Otello pushed Desdemona away, Bassénz’s increasingly fraught response – ‘E son io l’innocente/ cagion di tanto pianto!/ Qual è il mio fallo?’ (And am I then the innocent motive of these tears! What sin have I committed?) – was emotively coloured and shaped. The ‘Willow Song’ conveyed both Desdemona’s essential animation of spirit and the waning of her self-belief; it was an engaging narrative swelling with latent emotional currents. The richness of the song contrasted with the ensuing still limpidity of her Ave Maria – some lovely string playing here – which brought forth Desdemona’s own Madonna-like purity. This was refined singing, exhibiting subtle control and insight; it was a pity that the music-drama was interrupted at this terribly tender moment by the enthusiastic audience’s applause.

In the minor roles, Piotr Buszewski was an urbane Cassio, handsome of figure and voice, aptly suggesting courtliness and guilelessness, and if not particularly powerful then at least honeyed of manner and melody. As Roderigo, Andrés Presno’s tone was suitably sweet to suggest a besotted lover. Monika-Evelin Liiv was a forthright, outraged Emilia in the closing moments, and Romanian bass Alexander Köpeczi possessed impressive gravity and composure as Ludovico.

Boito’s compression of Shakespeare’s play means that the escalation of Otello’s jealousy can feel lacking in explanation or credibility. The ROH Orchestra under the baton of Daniele Rustioni captured some of Verdi’s dramatic breadth and sweep, however, communicating how the seeds of jealousy are sown, nurtured and harvested. The orchestral playing was especially precise and powerful in Acts 3 and 4, incisively responsive to the emotive and dramatic details, with colour, dynamics, textures finely graded and alert – a welcome supplement to Warner’s chiaroscuro minimalism.

Claire Seymour

Verdi: Otello

Otello – Russell Thomas, Desdemona – Hrachuhí Bassénz, Iago – Christopher Maltman, Cassio – Piotr Buszewski, Roderigo – Andrés Presno, Emilia – Monika-Evelin Liiv, Montano – Blaise Malaba, Lodovico – Alexander Köpeczi, Herald – Dawid Kimberg; Director – Keith Warner, Revival Director – Isabelle Kettle, Conductor – Daniele Rustioni, Set designer – Boris Kudlička, Costume designer – Kaspar Glarner, Lighting designer – Bruno Poet, Movement director – Michael Barry, Fight director – Ran Arthur Braun, Orchestra and Chorus of the Royal Opera House.

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; Tuesday 12th July 2022.

ABOVE: Hrachuhí Bassénz (Desdemona) Russell Thomas (Otello) © 2022 ROH / Clive Barda