“Be not afeard,” Caliban reassures the comic conspirators, Stephano and Trinculo, “This isle is full of noises,/ Sounds and sweet airs that give delight and hurt not.” Indeed, the whole action of Shakespeare’s The Tempest is driven by airs sweet and stormy: from the turbulent thunder that shipwrecks the Neapolitan aristocrats on Prospero’s island; to Ariel’s songs, mischievous and malign; to the wedding blessings of Juno and Ceres in the masque which symbolise the play’s movement from discord to concord. Music is the agent of such transformation, as it is the origin of the play’s spectacles and magic.

No wonder, then, that The Tempest has received more operatic settings – and a few ‘near misses’, too – than any other play by Shakespeare. La tempesta, by the French composer Fromental Halévy (1799-1862) is probably not the first of those settings that comes to mind, however; there has been no modern production of Halévy’s opera. So, this Wexford production – directed by Roberto Catalano, designed by Emanuele Sinisi (sets) and Ilaria Ariemme (costumes), and conducted by Francesco Cilluffo – which opened the 71st Festival, offered a welcome opportunity to rediscover and reassess a half-forgotten operatic adaptation of the Bard.

First performed in 1850x at her Majesty’s Theatre – the home of Italian opera in London in the first half of the 19th century – La tempesta was an odd ‘European’ project. The text was written by the French librettist Eugène Scribe which was then translated into Italian by Pietro Giannone. Christopher Hendley, in his 2005 PhD dissertation, ‘Fromental Halévy’s La Tempesta: a study in the negotiation of cultural differences’, puts its thus: ‘Two Frenchmen recast a sixteenth-century English play as an Italian opera for an English audience.’

The premiere was, according to most accounts, a stunning display of music, dance, and spectacle. The Illustrated London News (15 June 1850) declared that Scribe had excelled in adapting The Tempest to meet the expectations of London’s operagoers: ‘Such a truly artistic work has seldom been seen on any stage; it is full of charming contrasts, employs every resource of modern art, and is free from all that is meretricious, glaring, and noisy. It was repeated on Tuesday and Thursday with increased effect.’ Much of the success was also attributed to the superlative cast assembled by the theatre manager, Benjamin Lumley, which included the baritone Filippo Coletti as Prospero, the soprano Henrietta Sontag as Miranda, the dancer Carlotta Grisi as Ariel and the bass Luigi Lablache as Caliban.

Anyone expecting a musical response to the various themes which enrich Shakespeare’s play would be disappointed, however. Scribe’s libretto had originally been offered to Mendelssohn who expressed reservations – chiefly concerning deviations from the original literary text – and negotiations between the composer and librettist eventually broke down. It’s worth remembering, though, that Scribe’s main intent would have been to furnish a composer with opportunities to fulfil the requirements of Italian opera.

Initially, Scribe’s action largely follows the bare bones of Shakespeare’s plot. After the storm, conjured by Ariele, which shipwrecks the Neapolitan usurpers, Prospero talks to Miranda of the island – though he leaves out much of the history of his duchy – and makes it clear to the audience that he is scheming for his daughter to marry Alonso’s son, Fernando, in order to regain his dukedom. During the lengthy expository material, Calibano is put to service, carrying logs.

At this point, the opera takes a sharp swerve from Shakespeare. Calibano’s mother, Sicorace (Sycorax), from whom Prospero has stolen the island, is alive and well, and imprisonment in a rock is no impediment to her sorcery. She bestows upon her son some magic petals which will grant three wishes to their possessor – a useful operatic trope – and instructs him to use his requests to help her escape from imprisonment, release himself from slavery and regain the island from Prospero. Caliban proves less than pliant, however. Afraid of Ariele, he bewitches the sprite and imprisons it in a tree, and then pursues his passion for Miranda, as Scribe makes the savage’s attempted rape of Prospero’s daughter – part of the ‘back-story’ of Shakespeare’s play – the fulcrum of the plot.

There follows an assemblage of rather disconnected scenes. Stefano gets Calibano drunk on rum – there’s no comic sub-plot, but it’s a neat opportunity for a brindisi and baccanale. An angry Sicorace intervenes again, convincing Miranda that Fernando is a false lover and that she must kill him, or her father’s life will be at risk. But, as Miranda is about to drive her dagger into the sleeping Fernando, he calls out her name and she wavers. Prospero appears before the Neapolitans (who have been entirely absent from the action thus far) and – substituting for Shakespeare’s harpy-Ariel – tells them of the ‘death’ of Fernando that has resulted from their greed and treachery; their distress is his vengeance fulfilled. In the end, a reconciliation of all parties is achieved.

So, there’s no hint of a colonial context; none of Gonzalo’s utopian idealism; no questioning of Prospero’s own flaws, motivations and oppressive control of those on the island; no parallel usurpation plots. More troublingly, there’s almost no magic or spectacle – the latter was supplied originally by ballets in the French grand opera tradition. The storm is rather a damp squib, there’s no banquet, no masque, no chess scene, and no diegetic songs for Ariel. Only Sicorace’s sorcery seems to have any potency.

This rather one-dimensional libretto, which has Caliban’s passion and savagery at its core rather than Prospero’s desire for vengeance, a cast of flat-pack characters, and which at times lacks clarity as the scenes unfold, needs a director pick it up by the scruff of its neck and impose strong dramatic cohesion and impetus. Roberto Catalano opts for abstraction. The design is monochrome, evil and goodness are literally black and white – there’s no room for moral ambiguity here. A grey façade stretches across the stage; from time to time, Prospero, Ariele and other figures appear in arched niches aloft, to watch events unfold. At the centre of the façade is a jagged cave-like opening, above which is inscribed ‘NOSTALGIA’ – a rather odd motto, since Shakespeare’s The Tempest is ultimately concerned with moving forwards not looking back.

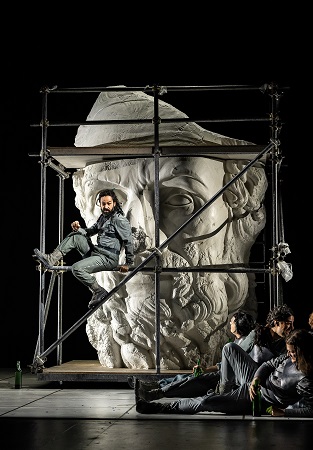

Catalano introduces some metatheatrical tropes. Initially, a spotlight is placed stage-right, besides a cement-mixer – the latter presumably alludes to Prospero’s attempt to build an island empire, evidenced by the motley figures in black (Scribe’s spirits, sylphs and sylphides, one presumes) who lug about baskets of bricks. Later, Fernando is surrounded by a circle of low floor-lights and sings in a ring of illumination. A double loudspeaker descends to relay Sicorace’s off-stage commands. The rock in which Ariel is buried is a huge, crumbling marble bust of Zeus (?) which is wheeled on upon a metal scaffold covered with flapping white sheets. Standing mirrors confront characters with self-images, a possible nod towards psychological growth and complexity, perhaps.

Such devices don’t furnish dramatic clarity though. Similarly, the opening moments don’t make a dramatic splash. Scribe describes the deck of a ship upon which the Neapolitans are sleeping, their dreams troubled by the voices of invisible avenging spirits who threaten the vengeance of Heaven for the cruelty they have inflicted upon Prospero. Designer Emaneule Sinisi populates the gloomy stage (lighting design, D.M. Wood) with iron-frame hospital beds on which the travellers lie, clutched and clawed at by shadowy black figures. These figures reappear in later scenes where they respond to the action with stylised slinking, contorted convulsing, willowy arm-waving and, when Zeus’s head is defaced with Trinculo’s drinking companions’ rum, with vigorous floor-mopping. Perhaps they are supposed to intimate the chorus of Greek tragedy?

Whatever the deficiencies of the libretto and the vagaries of this production, Halévy’s opera is well-constructed musically, and notable for its expressive melodic writing and imaginative instrumentation – the latter by turns stirring and elegant. And, the Wexford cast were absolutely engaged throughout the performance.

As Prospero, the Russian baritone Nikolay Zemlianskikh, who is currently a Wexford Factory Artist, displayed a very appealing baritone and a strong stage presence. Tall, dressed in an elegant white suit, he delivered his opening romanza with authority, the cadenza to the final stanza confident and powerful. Likewise, Prospero’s haranguing of the conspirators in the closing act had musical and dramatic stature. It’s a pity that Prospero is pushed by Scribe to the side-lines for much of the opera, occasionally glimpsed ponderingly clutching his book of magic, and undergoes no character development or moral transformation, for it would have been good to have heard more from Zemlianskikh.

The Israeli soprano Hila Baggio’s Miranda is no passive, obedient daughter. Baggio injected energy into her coloratura and demonstrated dramatic and vocal stamina. She relished the floridity of Miranda’s Rossinian cavatina in Act 1, perhaps singing with a bit too much abandon in the cabaletta where the stratosphere became a little squally at times. Her Fernando was Guilio Pelligra. The Italian tenor lacked the necessary smoothness and relaxation in his opening cavatina and struggled to climb to the top, but he worked hard to sing with lyrical force throughout, and Act 2 found him on more sympathetic ground. His duets with Baggio were emotionally persuasive despite the text’s verbal clichés, and he even managed to make Fernando’s declaration that it would be sweet to be stabbed in the heart by the one to whom one has given one’s own heart surprisingly convincing.

Originally the role of Ariele was a mute one, the sprite’s magic and grace performed by a dancer in the opera’s ballets and a Spirit of the Air added to the cast to assume Ariele’s voice. Here, there were no ballets, and Ariele was sung by the Irish soprano Jade Phoenix who participated in the Wexford Opera Factory in 2020 and 2021. This was a very impressive professional debut. Phoenix’s bright tone and clarity were just right for this Ariele, who shows little of the petulance or dissatisfaction of Shakespeare’s airy spirit, and is rather a happy-go-lucky mischief-maker eager to please their master.

As Calibano, the Georgian bass Giorgi Manoshvili offered a standout performance, his licorise-y bass imbuing the savage slave with dignity and stature. At times he seemed a genuinely tragic, Romantic figure, though the staging of the scene in which the petal-drugged Miranda is subject to his lascivious gaze and stroking struck a more unsettling note. The opera’s shift of focus, from Prospero to Calibano, is evidenced in some challenging and extended solos, in which Calibano laments the hardship he is forced to endure, issues musical diatribes, and plots to fulfil his desire for Miranda, and Manoshvili sang with impressive flair. He’s one to watch.

The smaller roles are scarcely characterised but Rory Musgrave (Alonso), Richard Shaffrey (Antonio) and Dan D’Souza (Trinculo) sang with accomplishment. Emma Jüngling made Sicorace’s stratagems striking and potent, and as Stefano, Gianluca Moro made good use of his engaging, nimble tenor in coaxing Calibano and the crew into inebriate carousing. Halévy’s choral numbers are characteristically stirring, and the prayer sung by the ship’s company before the ship is grounded on the rocky shore was vivid.

In his second year as Principal Guest Conductor at WFO, Francesco Cilluffo characteristically drew evocative playing from the Wexford Festival Orchestra, balancing the score’s lyricism with its finely delineated instrumentations and crisp textures, and spanning a wide dramatic palette.

Scribe offers an unambiguously happy ending. Caliban abandon his usurpation plan, once he realises that the petals power has been plundered. Prospero is presented upon a throne with Antonio and Alonso seated either side, and the marriage of Fernando and Miranda is blessed by their respective fathers. At the wave of Ariele’s wand, the palace is transformed into a splendid ship in which all will sail back to Milan – all except Calibano who is sentenced by Prospero to life alone on the island.

Catalano effects a rather different transformation. The iron-bed upon which Fernando had been sleeping becomes an ‘ocean’, as the black-clad figures pour buckets of water into its frame, and Prospero floats a frail paper boat on the waves. Far from being proud to be monarch of his own island, this Caliban sinks to the ground and rests his head devotedly on the reclining Prospero’s leg. The final image as is ambiguous as the opening one.

That said, this La tempesta is definitely worth seeing. Halévy and Scribe served up what the London public wanted in 1850 and this Wexford cast are absolutely committed to bringing their opera to life after its long silence.

The 71st Wexford Festival Opera continues until 6 November.

Claire Seymour

Fromental Halévy: La tempesta

Prospero – Nikolay Zemlianskikh, Miranda – Hila Baggio, Ariele – Jade Phoenix, Calibano – Giorgi Manoshvili, Alonso, Re di Napoli – Rory Musgrave, Antonio – Richard Shaffrey, Fernando, Principe di Napoli – Giulio Pelligra, Trinculo – Dan D’Souza, Stefano – Gianluca Moro, Sicorace – Emma Jüngling, Dancers – Sara Catellani, Andrea Di Matteo, Nicola Marrapodi, Giada Negroni, Andrea Carlotta Pelaia, Alessandro Sollima; Director – Roberto Catalano, Conductor – Francesco Cilluffo, Set Designer – Emanuele Sinisi, Costume Designer – Ilaria Ariemme, Choreographer – Luisa Baldinetti, Lighting Designer – D.M. Wood, Wexford Festival Opera Chorus and Orchestra.

O’Reilly Theatre, National Opera House, Wexford; Friday 21st October 2022.

ABOVE: Giorgi Manoshvili as Calibano © Clive Barda/ ArenaPAL