Finding myself with an hour to kill before a performance of Robert Carsen’s new production of Aida at the Royal Opera House earlier this week, I settled down in a small bar in Covent Garden with a glass of wine and a copy of If Not Critical – an edition of ten lectures by Eric Griffiths which were originally delivered at the Faculty of English at Cambridge University. ‘A rehearsal of Hamlet’ begins with reflections on the various small changes to the title of Shakespeare’s play – ‘Revenge’, ‘Tragedie’ and ‘True Chronicle Historie’ appeared in turn in early printings – leading Griffiths to reflect on the play’s genre and more generally on the critical opinion in Shakespeare’s time about the boundary between history and poetry. Drawing on Aristotle’s Poetics, he suggests, ‘History tells us what in fact happened, poetry lays out the pattern according to which we could have seen the events coming’.

Griffiths’ ensuing intellectual and critical probing is characteristically wide-ranging in its allusiveness and broad in its conceptualisation. But, this distinction between history and poetry – and Aristotle’s assertion of the greater ‘philosophic and graver import’ of the latter, ‘since its statements are of the nature rather of universals, whereas those of history are singulars’ – stayed in my mind during the opera performance later that evening, since it seemed to me that one might argue that Carsen had sought to position Aida as poetry – representing Aristotle’s universals, ‘what such or such a kind of man will probably or necessarily say or do’ – rather than as ‘history’.

In many ways, Aida is bound up with contemporary history, however. When Ismail Pasha, the new Viceroy of Egypt, arrived in Paris to represent his country at the Exposition universelle in June 1867, the Egyptian pavilion that he had erected on a large corner of the Champs de Mars – featuring, among myriad things, a pharaoh’s temple, a modern-day bazaar, and a panorama of the Isthmus of Suez created by the Suez Canal company – was described by one French commentator as ‘a living Egypt, a picturesque Egypt, the Egypt of Ismail Pasha’. His lavish spectacle was almost certainly designed to present Egypt as a major player on the modern world stage, and this idea also lay behind his commission, two years later, of Verdi’s Aida, which was to be performed in Cairo’s first opera house, positioned beside the recently opened Suez Canal.

Contemporary political events in Italy and France, such as the reunification of Italy under Victor Emanuel II in 1870, the collapse of the Second Empire after France’s defeat in Sedan that year, were to cause the postponement of the planned premiere of Aida in Cairo, and subsequently, the European premiere at La Scala. Moreover, scholars have argued about the opera’s representation of Egypt. Where the protagonists in Aida designed to play a part in representing a new political order of Egypt at the end of the nineteenth century? Is Aida an ‘Orientalist opera’, a portrait of the non-European as seen through contemporary Italian eyes, as Edward Said has argued – not ‘about but of imperial domination’? Or, is Paul Robinson correct when he suggests that the dynamic between oppressor and oppressed in Aida is easily translatable into Italian terms, and thus the ‘ideological universe on display’ in the opera can be seen as an allegory of Risorgimento politics, in which Egypt plays the role of Austrian oppressor?

Carsen isn’t interested in such questions. He eschews the original historical and geographical setting of Verdi’s Egyptian spectacle – out go Egypt, Ethiopia and elephants, pyramids and palm trees, and all the customary trappings associated with Aida – and sets the action in an unnamed modern-day totalitarian state. Struck by the frequency with which three words – guerra, morte, patria – recur in the libretto, Carsen professes to have focused on the opera’s presentation of intense conflict between personal feeling and patriotism, and the way that individuals are ‘caught up and often destroyed by the forces of state and religion’. He’s also concerned with the aggression of a large, power state as it attempts to invade and dominate a smaller state. Preparations began in 2018 for this production, which was delayed by the pandemic, but recent world events make his interest in this dynamic seem prescient.

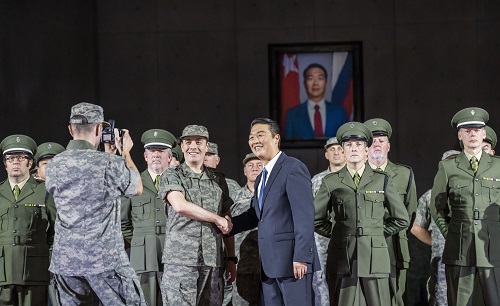

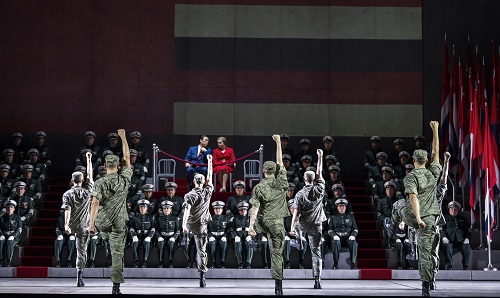

Set designer Miriam Buether has thrown away the gold paint and places the action in a vast grey bunker. Indeed, there’s a distinctly ‘underground’ ambience – the sun certainly never shines in this concrete realm – and the set almost seems to anticipate the entombment of the condemned lovers in the opera’s final moments, adding to the prevailing sense of hopelessness. Annemarie Woods dresses the cast and chorus in spick-and-span military dress, and the ROH Chorus excel, not just, as always, in their immaculate and precise singing, but in their flawlessly regimented military manoeuvres.

The might and arrogance of grand military parades in North Korea or the old Soviet Union come to mind, though Carsen explains that he took inspiration from three states, China, Russia and the US – as the red-white-and-blue flags which parade the patriotism and propaganda, and alleviate the starkness of the design, attest. When the flags are draped over coffins and ceremoniously borne off-stage during Act 2’s Triumphal March, it’s hard to push aside memories of Vietnam, Iraq and Afghanistan. Lighting Designer Peter Van Praet picks up the glints of colour offered by some of the principals’ attire, adding to the ‘weight’ of the bunker’s oppressiveness.

Does Carsen’s approach work? Well, there are some rough edges. References and prayers to the gods seem incongruous within this military regime, and the director doesn’t always find something engaging to replace the ostentatious ceremonies and dances – there are only so many times that a soldier saluting can hold one’s interest. Moreover, the lovers’ plight is rather overwhelmed by the totalitarian apparatus, and the decision to entomb them in an underground weapons silo might make for a provocative closing image but also seems to invite a potentially explosive escape.

That said, one doesn’t miss the glamour, nor the elephants, and the austere proves just as powerful and arresting – visually and dramatically – as the exotic. The soldiers’ whispered prayer, as they sit with their assault rifles to hand, is astonishingly moving. The dance (not by Moorish slaves, but by soldiers in combat fatigues) which follows the Triumphal March, choreographed by Rebecca Howell, brilliantly captures both the brutality and the artistry of hand-to-hand combat, and that Act concludes with video footage of combat culminating devastatingly destructive explosions – the images of obliteration a chillingly accompaniment to the eruption of choral sound.

Carsen’s wish to show the destruction of the individual by the apparatus of the state is powerfully fulfilled by the three principals. Francesco Meli is an upright, proud Radamès, very much a man of patriotism and integrity, but convincingly humbled by love. His tenor reached strongly to the top, but sometimes without nuance, though he paced his performance effectively. As Aida, Elena Stikhina gave an astonishingly insightful portrait of emotional suffering and inner conflict. This was not a showy performance, and at first I wondered if her soprano would rise above the resounding orchestral forces, but she saved her vocal intensity for the latter stages of the opera where it made a tremendously affecting impression. Rarely has torment and anguish sounded so sweet. Agnieszka Rehlis’s Amneris transformed persuasively from a spoilt, contemptuous schemer to a woman rent apart by despair when her pleading with the priests fails to save Radamès from his fate.

In the smaller roles, Ludovic Tézier was a big presence as Amonasro and Soloman Howard was imposingly, physically and vocally, as Ramfis – the latter received some of the loudest acclaim at curtain call. As the Egyptian King, In Sung Sim was authoritative, while Francesca Chiejina sang the off-stage role of the High Priestess with precision and clarity.

If colour was absent from the stage, then there was plenty of it in the pit where Antonio Pappano mined all the subtleties of the score, from the most delicate string sound to the heights of orchestral opulence. Time and again, the sensitivity of his reading brought balance, and human warmth, to the grim austerity of the design and the tragic tone of the drama. To take just one moment, Aida’s wrenching mourning after she has been condemned by her father: here, the soft darkness of the lower strings and bassoon wonderfully underscored Aida’s desolation and the pathos of her lament.

‘The artist who represents his country and his time becomes necessarily universal in the present and in the future.’ So Verdi wrote to the Neapolitan painter Domenico Morelli on 27th February 1871. One hundred and fifty years later, while not everything in this production comes off, Robert Carsen’s Aida might be said to illuminate the rightness of the composer’s words.

Claire Seymour

Aida – Elena Stikhina, Radamès – Francesco Meli, Amneris – Agnieszka Rehlis, Amonasro – Ludovic Tézier, Ramfis – Soloman Howard, King of Egypt – In Sung Sim, High Priestess – Francesca Chiejina, Messenger – Andrés Presno; Director – Robert Carsen, Conductor – Sir Antonio Pappano, Set Designer – Miriam Buether, Costume Designer – Annemarie Woods, Lighting Designers – Robert Carsen and Peter van Praet, Choreographer – Rebecca Howell, Video Designer – Duncan McLean, Orchestra and Chorus of the Royal Opera House.

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; Monday 3rd October 2022.

ABOVE: A scene from Aida at the Royal Opera House © Tristram Kenton