Of standard repertoire operas, Richard Strauss’s Elektra may be the toughest to perform. It requires a gargantuan orchestra of extreme virtuosity, a conductor who can mold 100 minutes of increasing tension into a coherent whole, and singers who can tirelessly project extreme emotion through the medium of an intricate German text. Above all, the title demands a dramatic soprano who commands the stage at full throttle for 100 continuous minutes.

Christine Goerke began her career several decades ago as a successful singer of Handel, Gluck, and Mozart. After a vocal crisis and near retirement, she reemerged as a dramatic soprano specializing in a few Wagner and Strauss roles, among which Elektra has been the most successful. Over the past decade, she has reigned supreme in this part.

In that time, her voice has deepened, and her upcoming schedule places more emphasis on Amneris, Ortrud, and other mezzo roles. A decade ago, she perhaps sang Elektra with (almost imperceptibly) more purity, edge and precise intonation in the upper reaches – though her rendition remains uniquely impressive up to a fortissimo high C. Yet the real glory today lies in the richness and warmth of the middle and bottom of the voice, qualities perhaps unique in the recorded history of this opera.

Goerke does not slice through Strauss’s orchestra, as almost all sopranos do, but envelops it with a magnificent flood of golden sound. Without a hint of strain, she glories in the long-held (and often incestuous) money notes in the upper middle of the voice the E-flat’s as she recognizes her brother and repeated F’s and G’s as she invokes her father. A committed performer, she gives 100% throughout, yet the voice even across registers, but for the very sparing use of an impressive chest voice to project low notes that regularly go missing in live performances.

Even clips of performances such as this shortchange the impact of such vocal opulence: you just have to be there. Live in an acoustically resonant house such as the Kennedy Center, it was a uniquely memorable performance.

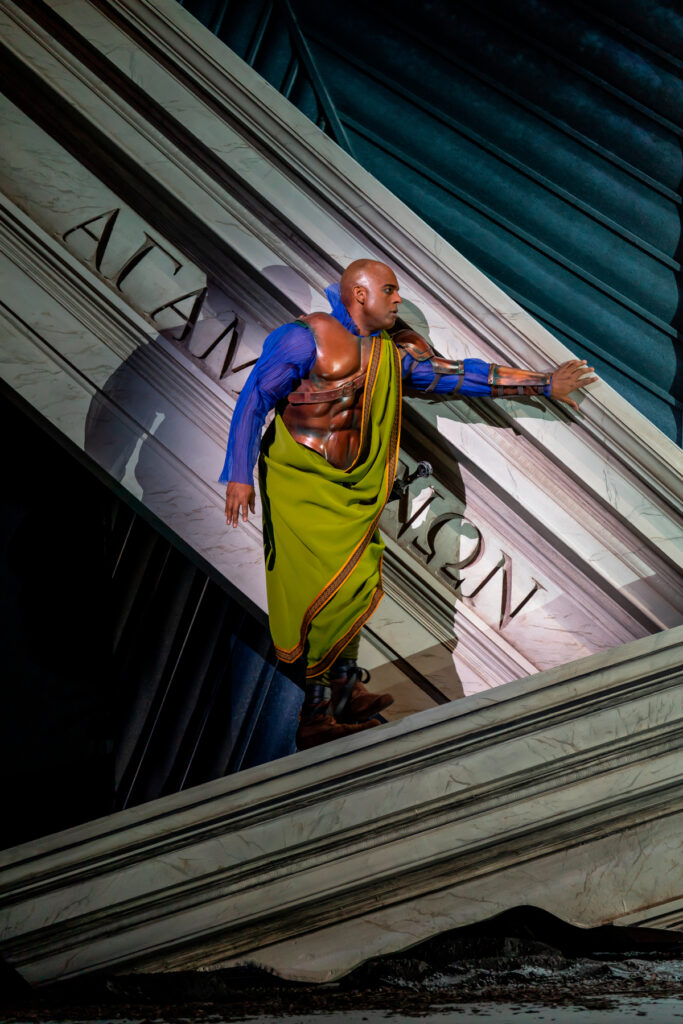

Extraordinary for different reasons was bass Ryan Speedo Green. When he first emerged as a trainee in the Met Young Singers’ Program, his unusual back story – a poor kid of color rescued from Virginia reform school by a sharp-eared vocal teacher and eventually hired at the Met – inspired a book-length biography and countless articles.

Today, a decade of artistic training and discipline have produced the clear diction, dark vocal timbre, elegantly etched tone production, and commanding stage presence of a truly great singer. Green’s performance of Elektra’s brother Orest matched the best I have ever heard. And he is only thirty-six, an age at which most basses have yet to enter their prime. If this trajectory continues, he could emerge as a leading deep bass of his generation.

Small-town Michigander Sara Jakubiak has worked her way up through American conservatories and the German opera system. She is now much in demand across Europe and the US, especially in Wagner and Strauss roles. Her hard-edged laser beam soprano punched brilliantly through Strauss’s orchestration with no loss of intonation or diction – though the motivations of Elektra’s warmly maternal sister remained a bit unfocused. Maybe she is really an Elektra of the future.

Less than a decade ago, Swedish soprano Katarina Dalayman was herself a noted Elektra. Recently she shifted from soprano to mezzo roles – among them Elektra’s moody mom Klytämnestra. An accomplished artist, she offered moments of intelligent and convincing characterization. Yet, at least the night I attended, she simply lacked the power to cast a clear image of this unique character poised between victim and witch.

Veteran Slovak tenor Štefan Margita’s reedy and slightly effeminate Aegisth suited his eerie colloquy with Elektra, but allowed the fortissimo orchestration to bury his signature set-up line (before being murdered): “Hört mich niemand?” (“Does no one hear me?”). Other singers – many associated with the young artist program in Washington – offered clear and lively support, not least Meredith Arwady, who delivered the opera’s first line. “Wo bleibt Elektra?” (“Where is Elektra?”) in a memorably dusky contralto.

Yet I could not shake a nagging sense that, overall, the evening remained less than the sum of its parts. This resulted in part from casting against type: the personality conflicts were sometimes obscured by the choice of a warm-voiced Elektra, a steely Chrysothemis and a pallid Klytämnestra. But responsibility lies also with decisions taken by the two individuals tasked with assuring that a production coheres.

One is Washington’s Music Director Evan Rogister. He conducted in an orderly way and the orchestra responded with beautiful tone and technical finesse. Yet his conception of this unique score seems still a work in progress. Some sections seemed breathless, others lugubrious – the latter, for example, in Elektra’s monologue. Throughout, one missed orchestral inner voices and the lilting dotted rhythms that power critical passages forward – particularly important here, given the quirks of the reduced orchestration that the WNO’s small pit imposed upon it.

Equally problematic was the stage direction. Erhard Rom’s sober set and Bibhu Mohapatra’s color-differentiated costumes set a properly archaic mood, yet WNO Artistic Director Francesca Zambello added too many fussy and confusing little moments of indecision, neurosis and (most irritatingly to my mind) comedy. This undermined Goerke’s natural dramatic sincerity, obscured the remorseless drama, and blunted its deliberately delayed (and, therefore, all the more shocking) revelation of just how dysfunctional Elektra has become.

In this regard, the most puzzling addition was a “Hollywood” ending, Admittedly, Elektra’s self-absorbed Dionysian dance is difficult to stage convincingly, dramatic sopranos being what they are. Yet the solution is surely not to instruct Elektra to “meet and greet” the entire household (right down to the meanest of the serving girls) and then to die surrounded by her family.

This double reconciliation belies the clear dramatic intent of the opera. According to the librettist Hugo von Hofmannsthal, as well as Strauss himself, the final scene shows that normal human interaction becomes impossible for someone such as Elektra, who has spent decades obsessing about past wrongs. She has lost the ability to recognize (let alone reintegrate into) family and society – especially, ironically, when the revenge she longed for arrives. Elektra’s PTSD-like state of non-comprehension expresses the true message – and the true horror – of this story.

Strauss’s music reinforces Hofmannsthal’s intent. Elektra sings explicitly of being able neither to hear nor to see anyone else; she hears instead only the music that “kommt doch aus mir heraus” (“the music that pours out of me”) – a denouement that, as Carolyn Abbate and other leading commentators show convincingly, is necessary to establish Elektra as the true dramatic heroine. And Strauss underscores the point by having her sing these lines within a precise harmonic schema that separates her (in C major) from other family members (in E major). Isn’t it the dramaturg’s job to protect such essential elements of the text and score?

In the end, however, the extraordinary commitment and talent of the team of singers led by Goerke overshadowed these negatives. Washington is reputed to be a conservative opera town in which audiences are often put off – even by a pre-World War One modernist warhorse such as Elektra. Yet at the curtain, the audience rose as one for – long-time locals assured me – the most enthusiastic standing ovation they remember in this theater.

Andrew Moravcsik

Top image: Christine Goerke (left) as Elektra and Sara Jakubiak as Chrysothemis.

All photos by Scott Suchman courtesy of Washington National Opera.