When Ruggero Leoncavallo’s one-act dramma lirico, Zingari, premiered at the London Hippodrome in September 1912, the Manchester Guardian noted that the large audience greeted it with enthusiastic applause, repeatedly calling the composer back to the podium. The reviewer, however, found the gypsy-themed opera ‘pleasant and fluent’ but rather ‘devoid of character and stimulus’, remarking that the ‘quick felicitous touch’ of Pagliacci – which Leoncavallo had conducted to acclaim at the Hippodrome the preceding year – was no longer at the composer’s command. The final judgement was lukewarm: ‘Of operas like “Zingari” Leoncavallo could write a dozen and be known the worse for it, but such operas will not add to his fame.”

In a detailed liner book article about the opera and its context – which includes an interesting account of changes in music hall culture in the early 20th century – Ditlev Rindom observes that while the London public were highly enthusiastic about Zingari, in many of the contemporary reviewsa ‘[s]nobbish and even racist element is nonetheless discernible … with both the subject matter and Leoncavallo’s compositional style criticised’. Indeed, the Saturday Review was particularly scathing, noting that some of the audience ‘whose accents betrayed an Italian origin’ demanded arias be sung twice, even three times: ‘That this spoilt whatever there was of the dramatic in the plot mattered little to them.’

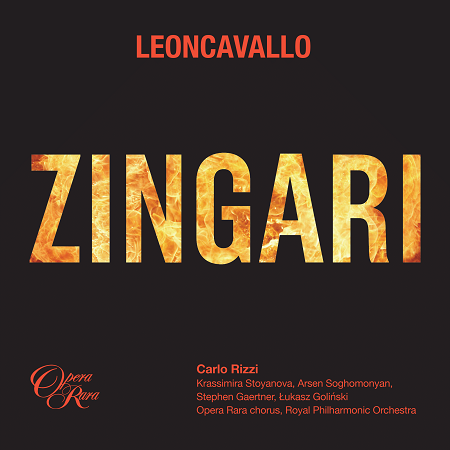

Despite this, Zingari, the tenth of Leoncavallo’s nineteen operas,was initially a hit when it travelled to Europe and the US. After the composer’s death, though, it languished in Pagliacci’s shadow and has been rarely performed since. Prior to this Opera Rara disc, which was released in September 2022, there have been three recordings, all of Italian broadcasts and which present the quite substantially revised version that Leoncavallo made subsequently – which include a radical change to the ending of the opera. There is no extant autograph score, and during WWII the original orchestral parts were lost when the archives of the Milanese publisher, Sonzogno, were hit by Allied bombing raids. There does exist, however, an autograph vocal score which accords with the vocal score, in Leoncavallo’s reduction, which was published in 1912. This Opera Rara recording thus presents the work as it was originally heard in London in 1912, restoring the omitted sections which have been re-orchestrated by Martin Fitzpatrick.

The libretto of Zingari (by Enrico Cavacchioli and Guglielmo Emanuel) was not the first to be derived from Pushkin’s narrative poem, Tsygany (The Gypsies, 1824). Indeed, in the Cambridge Companion to Pushkin, Boris Gasparov suggests that it ‘has inspired no fewer than eighteen operas – among them, Rakhmaninov’s Aleko (1893), Tsygany by Rimski-Korsakov’s disciple V. Kalafati (1941), Gli zingari by Ruggerio [sic] Leoncavallo (1912) and Zigäunen (1883) by Walter von Goethe (the poet’s grandson) – plus a half a dozen ballets’. Pushkin’s poem most likely had an influence on Bizet’s Carmen too, albeit indirectly, as Prosper Mérimée had read it in 1840 and translated it into French in 1852.

Presenting a tragic love triangle, the action echoes Pagliacci, Cavalleria rusticana and Carmen. Radu, an aristocrat, falls in love with the Roma free-spirit, Fleana, and swears allegiance to her band of gypsy comrades. They are married, but she tires of Radu and when the gypsy community comes under threat she rekindles her relationship with the Roma leader, Tamar, whom she had contemptuously rejected. When Pushkin’s jealous Radu finds Fleana and Tamar passionately declaring their love, he stabs them to death; in the revised version of the opera, Radu locks the door of their hut and ignites a conflagration which destroys them, and him. The recording presents Leoncavallo’s slightly less melodramatic original ending, in which the lovers burn but the Old Man advises the Roma to release Radu into exile, judging him a madman, rendered insane by passion.

One weakness of Zingari is the compression of Pushkin’s plot which means that the opera starts in a fervour and rapidly climbs higher and higher up the emotional thermometer, with no pause for breath or for expansion of character or situation. But, what might be dramatic hastiness in the theatre translates into one good tune after another on disc, and conductor Carlo Rizzi judges the temperature and the pace just right, letting the lyricism bloom, the tension tighten and the passions escalate. From the opening ‘anvil chorus’, as the evening descends on the gypsy camp, Rizzi draws vitalised playing from the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, and there’s a real spring to the rhythms sung by the 49-strong Opera Rara Chorus. The recorded sound is bright and crisp, and Rizzi makes unison orchestral lines sound lean and striving, while Leoncavallo’s colourful orchestrations glow. The two episodes which form the opera are separated by an Intermezzo which traverses diverse moods, from the dark, brooding czardas-like opening, through the mystery of virtuosic flute flutterings and oscillations above delicate harp and string pedals, culminating in impassioned surging by the strings and horns.

The four soloists make the most of Leoncavallo’s long-breathed melodism which frequently pushes the voices to the top and holds them there, is if the characters’ impassioned hearts have skipped a beat. Bulgarian soprano Krassimira Stoyanova glistens as Fleana, her melodies sumptuous but always refined, conveying the gypsy enchantress’s allure and hauteur. Fleana’s lines are often ornate and melismatic, as in the dance which the gypsies call for during the ceremony when she is married to Radu, and Stoyanova slips deliciously, and with an exotic tint, through the vocalise; there’s similar seductiveness when Fleana breaks up a fight between Radu and Tamar, but when she then taunts Tamar and contemptuously dismisses him, Stoyanova’s soprano blossoms rapturously, enhanced by lovely playing from the RPO strings and horns.

As Radu, Armenian tenor Arsen Soghomonyan introduces himself as a “prince of adventure”, and he certainly conveys both nobility and fearlessness as he yearns for “a wild and rebellious love/ as long as my sky is full of stars!”. And, as his star rises and then fades in Fleana’s orbit, so Soghomonyan’s robust tenor, which has a lovely darkness, evolves from sonorous ardour to inflamed suffering – he really does sound “mad with love”, then erupts with ferocity in the final scene in which Radu traps the lovers in the burning hut. American baritone Stephen Gaertner is no less intense and impassioned. His first aria, when he learns from the Old Man of Fleana’s love for Radu, is truly anguished, but his baritone throbs with passion when he declares his own passion. Tamar’s ‘canto notturno’, first heard off-stage and then reprised at the end of the opera, before the final love duet, is beautifully phrased above delicate pizzicato strings with woodwind murmurs interjecting. Polish baritone Łukasz Goliński conveys a sombre wisdom and fortitude as the Old Man, though there is soft warmth when he blesses the wedding couple as they make a blood sacrifice to seal their love.

The duets are the highpoints. In the first episode, Radu’s tenderness and earnestness are persuasively conveyed by Soghomonyan while Stoyanova negotiates the octave leaps effortlessly, her soprano crystalline and brilliantly controlled; the intervention of the off-stage women’s voices builds the duet to an ecstatic climax. The final duet for Fleana and Tamar has echoes of the Nedda-Silvio duet in Pagliacci, but is no less powerful for the association.

Presented with Opera Rara’s characteristic care and tastefulness, this neat boxed-disc contains a liner book with the aforementioned article, a synopsis in English, French, German and Italian, and a full libretto with English translation. Perhaps Leoncavallo’s attempt to revisit the style of his ‘big hit’ twenty years earlier might not have added to his fame, but Opera Rara certainly convince that those eager first London audience members were not wrong to delight in Zingari’s fervent lyricism and the fine singing they enjoyed.

Claire Seymour

Ruggero Leoncavallo: Zingari

Fleana – Krassimira Stoyanova, Radu – Arsen Soghomonyan, Tamar – Stephen Gaertner, Old Man – Łukasz Goliński; Conductor – Carlo Rizzi, Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, Opera Rara Chorus.

ORC 61 [64:00]

ABOVE: Arsen Soghomonyan, Krassimira Stoyanova, Carlo Rizzi, Stephen Gaertner & Łukasz Goliński