Three days before Lydia Steier’s 2019 production of Fromental Halévy’s La Juive received its first revival at the Staatsoper in Hannover, a British MP – a Minister for Immigration – gave a talk to a political thinktank in which he stated, ‘Put simply, excessive, uncontrolled migration threatens to cannibalise the compassion of the British public.’ As Orwell knew, defining, condemning and persecuting a ‘common enemy’ has long been a way for failing governments to shore up their own ranks. And, if one is inclined to doubt that the inflammatory language that has become sadly commonplace in political discourse – the divisive culture wars, and the talk of ‘invasions’ and ‘hostile environments’ that have characterised chaotic populism of late – has a sinister ring, then Steier’s shocking and startling production will surely banish such doubts.

La Juive, one of the most successful grand operas of its time following its premiere at the Paris Opéra in 1835, may tell a tale of religious fanaticism and intolerance – specifically medieval Jewish–Christian conflict – in Germany in 1414, but Steier confirms that Halévy and Eugène Scribe’s work is one of the most contemporary of political operas.

The backdrop to La Juive is the Council of Constance that took place in Switzerland between 1414 and 1418, during which the Catholic Church sought to resolve the divisions which had riven it for over a century and to condemn heresy. Scribe brilliantly brings together the public and the private, focusing not on ‘heretics’ such as Jan Hus, who was burned at the stake in 1415, but on a different kind of ‘outcast’, the Jewish goldsmith Éléazar and his vengeful, ongoing feud with Cardinal Brogni.

There’s some backstory. The Cardinal had condemned Éléazar’s sons to be burned at the stake in Rome and exiled the goldsmith; Éléazar then rescued the Cardinal’s daughter, Rachel, from the smoldering remains of his home, after it had been attacked by bandits. He has raised her as a Jew, but Rachel has fallen in love with the Christian Prince Léopold, who has disguised himself as a young Jewish painter, Samuel, in order to woo her. When Léopold is forced to reveal his true identity, Rachel denounces him before his wife, Eudoxie, setting in motion a chain of events which culminates in her refusal to save her own life by renouncing her Jewish faith, and in Éléazar’s ‘victory’ over the Cardinal as he reveals Rachel’s identity to her father at the very moment that she, unaware to the last of her Christian origins, is thrown to her death in a boiling cauldron.

Steier and set and video designer Momme Hinrichs confidently and vividly embrace the public spectacle of the work but brilliantly assimilate the grandeur and the protagonists’ private torment. In juxtaposing historical religious conflict and a tragic love story, they take us on a journey back through time, and in so doing persuasively confirm La Juive as an opera for our own age.

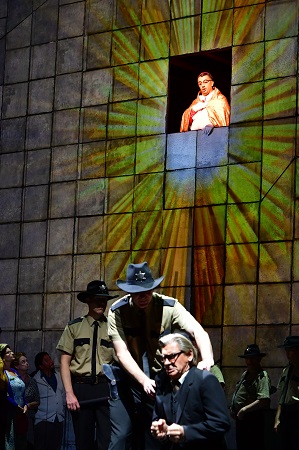

Act 1 is set in 1950s America. The fervent crowds, bubbling with over-excited evangelism, gather on grandstands to await the appearance of the Cardinal at a window of his palace – a niche in the grey stone wall which dominates the stage. Their near-hysteria is evident not only in the sparkling vibrancy of the ensemble singing – the Staatsoper Chorus (chorus master, Lorenzo Da Rio), its ranks swelled by extra members, are in terrific voice throughout – but also in the imagery, as projected cherubs float up the wall like strange hallucinations. And, in the surfeit of colour that contrasts with the dour, dark attire of Rachel and Éléazar, as the latter is condemned to death before a baying mob for wielding his jeweler’s anvil and tools on a Christian holiday, before the Cardinal grants a reprieve.

Cheerleaders in stars-and-stripes hot-pants whip up the avidity. The flayed, hanging Jewish corpses that are paraded through the crowd are little more than carnival exhibits: the grotesque has become the everyday, horror is met with indifference, death welcomed with glee. I couldn’t help thinking of Voltaire’s auto-da-fé, staged by the ‘sages’ of Portugal after the devastating earthquake which has destroyed three-fourths of Lisbon because they could ‘think of no means more effectual to prevent utter ruin than … burning of a few people alive by a slow fire, and with great ceremony’. And, so it is that ‘Candide was whipped in cadence while they were singing; the Biscayner, and the two men who had refused to eat bacon, were burnt; and Pangloss was hanged’. Voltaire concludes, ‘The same day the earth sustained a most violent concussion’. Steier creates the same sense of an almost insane and unstoppable illogic.

Act 2 returns to the dawning of the Nazi regime in 1930s Germany and takes us into Éléazar’s home, where friends gather with the goldsmith and his daughter to celebrate the Passover ritual in secret. Steier powerfully conjures the tensions of living under surveillance, of forever anticipating the ominous knock at the door, of having to scrub xenophobic graffiti from the walls of one’s home. The quiet, a cappella chorus is sung with beautiful focus and lyricism, only to be rudely interrupted by the brash arrival of Léopold’s wife, Princess Eudoxie, clutching her frivolous hand-bag dog and commanding Éléazar to make her a new piece of jewelry. The poignancy of the Act is deepened when we remember that the antisemitism that the opera depicts – and, some critics argue, perpetuates – made it impossible to stage in the years following the Holocaust; and that it wasn’t until the Vienna State Opera’s 1999 production that La Juive received its first major modern revival.

Act 3 is a riot of rococo excess, the fervent American crowds of the opening Act now transformed into wig-wearing aristocrats at the Stuttgart court of Duke Karl in 1738, where Rachel – informed by Léopold of his Christian faith – has entered the service of Eudoxie. Beneath the glitter, gold and gloss is a ghastly greed and gruesomeness, as a gargantuan feast turns into a sickening display of barbarity and perversion. Cardinal Brogni’s interrogation of the imprisoned and condemned Éléazar and his daughter, in Act 4, is set in Spain in 1492 – the year in which the Catholic monarchy issued the Alhambra decree, expelling the Jews. And, Steier returns us to the context of Scribe’s libretto in the final Act, taking us back to Constance in 1414 and reviving the festal brutality of her opening Act, the carnival carts and exhibits now exposed as instruments of death – the ‘one dime-a-dunk’ US fairground attraction now transformed into a grotesque medieval death-trap as Mickey Mouse henchmen drag Rachel to her execution.

Indeed, Steier and Hinrichs don’t just travel back in time, they increasingly merge epochs, so that the Renaissance mob in Act 4 acquires a Gothic gleam that is strangely modern, even futuristic; and, the candy-floss colours of the American crowd, with their bouffant hair and Elvis quiffs, translate into the colourful periwigs and painted faces of the eighteenth-century lords and ladies. It’s as if each of these settings is actually a version of the same place, and that place is our own world.

Repeating tropes accrue weight and urgency: cages, carts, feasts, processions. No image is more powerful than the one with which the production opens: a small boy, in long socks and shorts, wearing a yarmulke, quietly playing hopscotch, is shoved to the ground by another young child. Children learn from their parents; images of hatred become entrenched, second nature. In the final scene, the dead body of the Jewish boy will be dragged across the stage on a cart by his nemesis, just one of many dead Jews whom the crowds gather to ogle.

Aside from the grand spectacle, much of the inner energy of La Juive derives from the opposition of Cardinal Brogni and Éléazar, and in Shavleg Armasi and Charles Workman this production has a superb pair of adversaries. Armasi’s bass is rich and smooth, and he wields hypnotising authority – terrifyingly so in the interrogation scenes. Throughout, there’s a sureness about the phrasing, the long lyrical lines beautifully sustained; and, Armasi has the compass of the role which extends low but also makes demands at the top. This Cardinal is no mere effigy of power, though, and Armasi lets us see the man beneath the ecclesiastical robes, particularly when he becomes touched by a strange empathy for the young woman whom he is questioning. His self-flagellation in the final Act is a powerful and convincing moment of honest recognition and regret.

Éléazar is a problematic character, both genuinely suffering Jew and at other times a stereotypical Shylock-figure. He can seem obdurate, declining Brogni’s gesture of reconciliation in the opening Act, preferring to see his daughter die rather than reveal her identity in the last. Workman captures both the passionate intensity of the goldsmith’s faith and the depth of his paternal love. This Éléazar is filled with vengeful anger but also vexed with anguish. And, the tenor has both the agility and the steadiness – his stamina is unflagging – that the role requires. ‘Rachel, quand du Seigneur’ is beautifully sung, with an almost cantorial lyricism and a plaintive tone that exposes his vulnerability.

Hailey Clark’s wonderfully full-bodied, darkly inflected soprano conveys Rachel’s complex character. She has both the power and the range, and she projects thrillingly into the auditorium. Both Clark and Mercedes Arcuri have absolutely secure upper registers and when they soar together at the end of Act 3 it’s gripping – Arcuri’s bright gleam a lovely complement to Clark’s richness. Their duet in Act 4, when Eudoxie visits Rachel in prison and begs her to retract her confession and thus save Léopold’s life, is no less tense and compelling, and the fast, closing section draws superb singing from both.

The role of Léopold/Samuel is not a very sympathetic one. And, musically, all the challenges come at the start, with Samuel’s only aria being his Act 1 serenade (he’s entirely absent from the final two Acts). Sunnyboy Dladla makes a charismatic entrance in an open-top Cadillac and serenades Rachel with rock-and-roll flair, his warm tenor sailing up easily to the top. He negotiates the tricky ensemble passages with aplomb, too. Pavel Chervinsky (Ruggiero) and Yannick Spanier (Albert) complete the splendid cast.

Under conductor Stephan Zilias, the Lower Saxony State Orchestra relish Halévy’s imaginative orchestration and diverse instrumental effects.

When La Juive was revived at the Met in 2003, after an absence of almost 70 years, writing in the Washington Post (‘La Juive’s Hateful History’) Philip Kennicott asked, ‘Isn’t there something a bit creepy about a Jewish composer writing an opera, for a Christian audience, in which boiling Jews in oil becomes entertainment?’ Steier pushes such questions aside and, while not neglecting the antisemitism which underscores the narrative, asks broader questions. Can we learn from history? Are younger generations destined to relive the conflicts of the parents? Can art, opera, bring about change?

In so doing, Steier shows us the real political power of Halévy’s opera, and forces us to acknowledge the dangers of religious and ethnic hatred, to condemn the blind intolerance and despotism that leads man to persecute his perceived enemies. In taking us back to numerous pasts, Steier shines an unflinching light on the present, and into the future.

Claire Seymour

Rachel – Hailey Clark, Éléazar – Charles Workman, Léopold – Sunnyboy Dladla, Cardinal Brogni – Shavleg Armasi, Princess Eudoxie – Mercedes Arcuri, Ruggiero – Pavel Chervinsky, Albert – Yannick Spanier; Director – Lydia Steier, Conductor – Stephan Zilias, Set and video designer – Momme Hinrichs, Costume designer – Alfred Mayerhofer, Dramaturg – Martin Mutschler, Choir of Staatsoper, The Lower Saxony Orchestra.

Staatsoper Hannover, Germany; Saturday 29th April 2023.

All images (from the 2019 production) © Sandra Then