‘I believe hugely in advertising and blowing my own trumpet, beating the gongs, drums, to attract attention to a show.’ So wrote Phineas Taylor Barnum to a publisher in 1860, adding, ‘As a general thing I have not “duped the world” nor attempted to do so … I have generally given people the worth of their money twice told.’ But, while there’s no evidence that P.T. Barnum ever uttered the apocryphal phrase, ‘There’s a sucker born every minute’ – he may have loved a hoax, but he aimed to laugh with his audiences rather than at laugh – his exuberant career certainly was devoted to the art of self-promotion, in order to earn what he termed ‘notoriety’ for both himself and his ‘museum’ of ‘curiosities’.

However, in later years this self-styled Prince of Humbug started to take himself, and the world, more seriously. He became a champion of the temperance movement, a supporter of women’s rights, served as Mayor of Bridgeport and had a seat in the Connecticut General Assembly. And, he decided that, rather than mermaids, midgets and monstrosities, what America really needed was ‘art’.

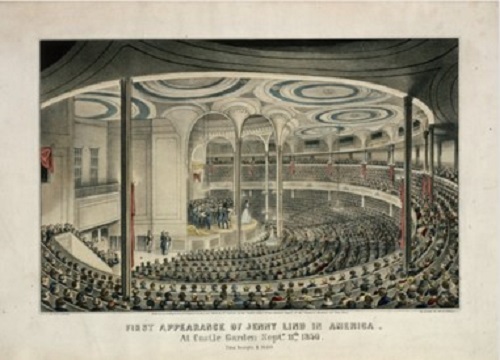

So, in 1850 Barnum imported Jenny Lind, the so-called Swedish Nightingale, the very embodiment of respectability and moral purity, persuading her to undertake a 150-concert tour of the United States – for a fee of $150,000, with ‘extras’ that the shrewd Lind negotiated with General Tom Thumb, including two servants, a horse and carriage, three traveling companions and $1,000 for each concert, in addition to the fee.

There was a problem, though. No one in the US had heard of Lind. Barnum himself had never heard her sing. Realising that the tour might wipe out his finances, Barnum set about marketing ‘the greatest singer who ever lived’, creating a merchandising phenomenon which saw Lind’s portrait published in newspapers, songs composed in her honour, and competitions launched for cities to bid to host concerts, with the first ticket in each city auctioned to the highest bidder. Her name was splashed across products from cakes to kettles, parasols to cigars, thimbles to soap.

When the steamship Atlantic docked in New York, so pervasive was Lindmania that almost 30,000 people climbed the rigging of nearby ships or gathered on rooftops simply to catch a glimpse of the Swedish soprano. They didn’t want to hear, just to see her. They were interested in the ‘star’ singer, not her song. Barnum had both invented the cult of celebrity and made ‘art’ a commodity, and in so doing raised ethical questions about the ‘value’ of art, and the relationship between commerce, consumerism and culture which continue to this day.

This collision of hyped-up celebrity and artistic idealism is the story told by composer Libby Larsen and playwright Bridget Carpenter in Barnum’s Bird, a two-act chamber opera which was co-comissioned in 2000 by the Plymouth Music Series and the Library of Congress in honour of the latter’s 200th anniversary. Director Ella Marchment’s production at the Royal College of Music is the UK premiere of the work – and it’s a fitting venue as, later in her life, when the RCM was founded in 1882 Lind was appointed professor of singing, one of only two female professors at the time.

Marchment explains that she sees the opera as presenting a clash of cultures, ‘a tension between art within the UK and the United States’ that she recognises in ‘the subtle shifts in the way that operas are staged’ in the respective countries. Certainly, Madeleine Boyd’s simple set and Rachel Astall’s striking spotlighting conjure the theatricality, the boldness and brashness that Marchmant identifies with American productions. Against a brick back wall, tall arches are manoeuvred to create intimacy and suggest interiors – Lind’s home, Barnum’s office – or evoke the flamboyance of the circus ring.

This mobility characterises the choreography (Adam Haigh) of the eight-strong chorus, too. Dressed in outré garb – a riot of clashing colours, stockings striped and chequered, ruffs, feathers, outlandish headpieces and garish make-up – Barnum’s Curiosities parade and pose, and form exuberant tableaux vivant, with 19th-century show biz flair. This effect is vivid and dramatic, comic acting and choral singing tightly fused, the movement never flagging.

At times the theatrical effect is more cabaret than opera, and that is true of Larsen’s score too, which blends minstrel tunes, marches and operatic arias within her own musical language. The latter prioritises rhythm over melody, and the vocal lines are quite declamatory – often echoing natural speech patterns, and at times drifting into the spoken word. Indeed, most of the ‘aria moments’ are just that, interpolations of operatic numbers, which might be designed to create comedy or pathos, though Larsen’s merging of different styles and idioms is complex and clever.

This is nowhere more evident that in the Act 2 concert sequence which sees Jenny Lind, having swapped her pure white gown for garish concoction of red ankle-boots and yellow-plumed bonnet, perform ‘Casta Diva’ while the chorus plead with her to “Do that fancy thing with your voice!” As Lind, soprano Lylis O’Hara retained her poise as she delivered Bellini’s lyric masterpiece, her tone both rich and sweet, her phrasing a model of beauty and emotion. The complexity of Bellini’s characterisation seemed here transferred to Lind, creating both sincerity and pathos.

This was a terrific performance by O’Hara who communicated strong sentiments in ‘Hear Ye Israel’ from Elijah – which Mendelssohn reportedly composed for Lind so that he could indulge his love of her voice, particularly her F-sharp! He wouldn’t have been disappointed here. And, O’Hara demonstrated superb control over her voice, especially at the top, when she performed Lind’s ‘echo song’, switching from forte to piano on the same pitches with stunning precision and purity. Larsen’s presentation of Lind is a sympathetic one. Though demure, there is little of Lind’s, perhaps unjust, reputation for primness and prudishness, and both her commitment to her art and her philanthropism – she undertook the tour at least partly to raise money to establish children’s orphanages in Sweden – seemed earnest, O’Hara evincing genuine warmth.

It was to Barnum’s advantage, of course, to portray Lind as angelic, and he was prone to eulogistic public statements, “What a great, heaven-inspired being she is! What a pure, true, artistic soul.” Tenor Dafydd Jones was robustly bombastic, resplendent in gold waistcoat, towering top hat and, later, ringmaster scarlet. Confident, opinionated and with a determined glint in his eye, Jones’s Barnum had carnivalesque chutzpah and a canny ‘nose’ for the next ‘big thing’. There was even something a little menacing about the way that Barnum manipulated others’ reality: “I dream your dreams.”

As Giovanni Belletti, Lind’s professional colleague, baritone Connor Dalton gave ‘Largo al factotum’ his all, producing a big, beefy sound with no strain, vocally matching his confident dramatic presentation of the self-loving opera singer. Larsen conceived of the diminutive General Tom Thumb as being portrayed by a puppet. Here, mezzo-soprano Charlotte Clapperton had a miniature puppet tucked under her chin, as it were, manipulating its arms and legs as she sang, her clean tone and bright sound convey Tom’s quick wit and directness.

Simon Brown sang Mr Dodge’s minstrel song, ‘Josiphus Orange Blossom’, in a warm comic mode while, as Charity, Jessica Lawley’s singing of ‘Jenny Lind’s Greeting to America’ – the result of a competition run by the Daily Tribune and won by the poet Bayard Taylor, whose ‘Greeting to America’ was set to music by Julius Benedict and sung by Lind at her concerts – was somehow simultaneously ‘hideous’ and charming!

In the pit, Michael Rosewell marshalled the pit chorus and small ensemble with vigour, matching the liveliness on stage. The instrumental group is small, just piano, percussion, three strings and flute, perhaps because of space restrictions in the venue for the premiere – and the piano tends to dominate. Though this does create a sort of ‘music hall’ or old-style ‘review’ ambience, more instrumental colour and flamboyance would be welcome, but Rosewell made much of what there is, conducting with clarity and conviction.

Lind managed only 95 of her projected 150 concerts, visiting 19 cities: New York, Boston, Providence, Philadelphia, Washington, Richmond, Wilmington, Charleston, New Orleans, Natchez, Memphis, St. Louis, Nashville, Louisville, Cincinnati, Wheeling, Madison and Pittsburgh – and squeezing in Havana in Cuba between Charleston and New Orleans. Exhausted, she bought out her contract and two years later returned home, a rich woman. Barnum’s bank balance was also supplemented to the tune of half a million dollars.

He would later remark, when challenged about one of his more extravagant self-promotional statements, “Such is the fact – and if it wasn’t, why still it ain’t a bad announcement”. So, in that spirit, perhaps Larsen’s Barnum Bird isn’t “the greatest show on earth”, but there’s no harm in praising a production which has charisma and comedic cheeriness – especially not when the performances are this good.

Claire Seymour

Jenny Lind – Lylis O’Hara, P.T. Barnum – Dafydd Jones, Tom Thumb – Charlotte Clapperton, Belletti – Connor Dolton, Mr Dodge – Simon Brown, Conductor – Ross Fettes, Charity Taylor – Jessica Lawley, Bayard Taylor – Tom Low; Director – Ella Marchment, Conductor – Michael Rosewell, Designer – Madeleine Boyd, Lighting designer – Rachel Astall, Choreographer – Adam Haigh, RCM Chorus and Opera Orchestra.

Britten Theatre, Royal College of Music, London; Wednesday 28th June 2023.

ABOVE: Dafydd Jones (Barnum) and Barnum’s Curiosities (c) Chris Christodoulou