This was an evening of big voices and grand theatrical vision. When Christof Loy’s production of Verdi’s La forza del destino was first seen at the Royal Opera House, in 2019, Anna Netrebko and Jonas Kaufmann were the big draw, as Leonora and Alvaro respectively. That might seem a tough double act to follow, but on the opening night of this first revival Sondra Radvanovsky and Brian Jagde proved more than a match for their predecessors, and Etienne Dupuis, as Carlo, equalled them, perhaps exceeded them, in terms of vocal heights and thrills.

There was a vocal intensity here that was absolutely compelling. The soloists’ passions swept through all, invigorating the ROH Chorus – enlarged, superbly choreographed (revival choreography, Klevis Elmazaj), blazing with colour and heft – and giving dramatic ‘lift’ to the scenography. First time around, I found some aspects of Loy’s conception less than convincing. This time, the dumb show in the overture – when we see the darts of destiny take aim at their targets – seemed brilliantly structured, the musical form perfectly matched to the unfolding dynamics between the youthful protagonists: childhood tussles become tragic conflicts. I noticed small details, such as the discarded guitar lying against a wall, which first time round didn’t catch my eye. The prayer motifs and the young child’s playing with a yo-yo distilled the opera’s fusion of the sacred and the secular, the erudite and the mundane, that unfolds with tragic consequences in the course of the following hours.

Christian Schmidt’s singular set emitted a claustrophobic grip, the shutters – opened to allow Alvaro entry in the dead of night – not letting in the light, and subsequently being (almost imperceptibly) transformed into a niche containing a crucified effigy of Christ, in the monastery where Leonora seeks refuge. Keeping the doors of the Calatrava palace in place throughout seemed a masterstroke, emphasising the way that familial conflicts conflagrate into a war which can destroy not just individuals but a nation. The opening of the door to reveal a transfiguring pathway of candles, at the end of Act 2 Scene 2, was brilliant theatre and deeply meaningful imagery. The remnants of the door-arches that made an entry-way for the military camp in Act 3 were a telling reminder of the causes of the conflict. The back-dop projections which before had seemed to me a little intrusive and unnecessary, now felt dramatically integrated and insightful. There was some wonderful chiaroscuro heightening of the dramatic confrontations and emotional peaks (lighting design, Olaf Winter).

Notwithstanding the vocal panache on display during the evening, I think that much of the impact of this opening night performance derived from conductor Mark Elder’s penetrating realisation of Verdi’s musico-dramatic pace and structure. There were heroic orchestral climaxes but there was lucidity too – and some wonderfully transparent textures and stunning woodwind solos that spoke as forcefully as the characters on stage. There was gruesome violence – some truly raw thunder-blows in Act 4 – but also delicacy and beauty. And, Elder swept the evening along with acute dramatic persuasion.

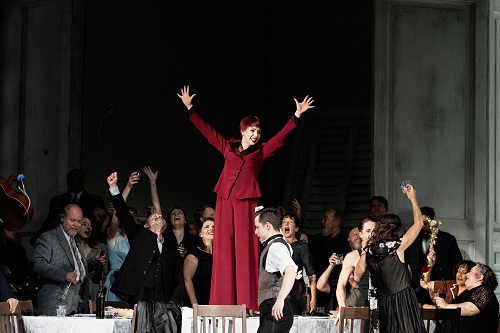

Radvanovksy dominated the first Act. ‘Me pellegrina ed orfana’ was a pained expression of conflicting loyalties which saw the soprano draw on a wide range of vocal resources, and an impactful chest register, complemented by orchestral utterances which emphasised Leonora’s emotional fragility. In Act 2, seeking sanctuary and atonement, her soprano became a silky sliver – wonderfully nuanced, the pianissimos no less ‘powerful’ than the punch.

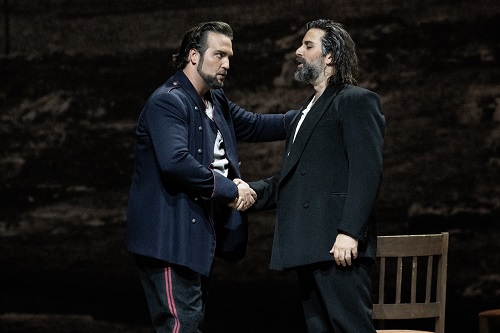

If Jagde sometimes seemed overly sturdy, then such robustness did match his characterisation of the impetuous and fearless Alvaro, and there was warmth and variegation in later scenes. The start of Act 3, when Alvaro finds himself leading a military camp in Italy, revealed new vocal subtleties – inspired, perhaps, and complemented by some superb clarinet playing. Alvaro’s ‘friendship’ and then confrontation with Etienne Dupuis’s Carlo were vocally visceral – theatrically edge-of-one’s-seat. Singing with refinement and lyrical poise throughout, Dupuis made Carlo’s exultation at the prospect of gaining vengeance for his father’s death a disturbing embodiment of the stranglehold of fate which holds him in its grip.

There were fine performances, too, from Chanáe Curtis as Curra and Evgeny Stavinsky as Padre Guardiano, the latter really make a mark dramatically – imposing of voice and stage presence. Vasilisa Berzhanskaya enjoyed Preziosilla’s stirring Rataplan, and was rigorous in its execution. As Fra Melitone, Rodion Pogossov was rather misanthropic. James Creswell’s Marquis of Calatrava didn’t make much of a mark in the opening scenes.

There is an article by George Hall in the ROH programme book titled ‘Grand Passions and Great Singing’. That says it all, really.

Claire Seymour

Donna Leonaro – Sondra Radvanovsky, Don Alvaro – Brian Jagde, Don Carlo di Vargas – Etienne Dupuis, Padre Guardiano – Evgeny Stavinsky, Preziosilla – Vasilisa Berzhanskaya, Fra Melitone – Rodion Pogossov, Mastro Trabuco – Carlo Bosi, Marquis of Calatrava – James Creswell, Curra – Chanáe Curtis, Alcalde – Thomas D. Hopkinson; Director – Christof Loy, Conductor – Mark Elder, Designer – Christian Schmidt, Lighting Designer – Olaf Winter, Choreographer – Otto Pichler, Revival Choreographer – Klevis Elmazaj, Chorus and Orchestra of the Royal Opera House.

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; Tuesday 19th September 2023.

ABOVE: Brian Jagde (Don Alvaro) © Camilla Greenwell