One of my opera-loving friends, a singer and musician herself and a regular devotee of both opera and ballet at the Royal Opera House and elsewhere, never attends performances of Rigoletto: the plot, she says, is just too horrid. Sitting in the stalls for this revival of Oliver Mears’ 2020 production of Verdi’s curse-laden, violent tragedy, I thought that perhaps she’s right: it was difficult during this performance to feel that this opera inspires any good thoughts about humanity – the sort of moral or spiritual catharsis that even the most painful and poignant dramas can produce.

Mears and his designer, Simon Lima Holdsworth, seem to go out of their way to emphasis the sheer nastiness of the opera. There’s the opening tableau which recreates Caravaggio’s The Martyrdom of Saint Matthew and reveals the Duke of Mantua and his entourage, slipping from staged Renaissance pomp to New Romantic sleaziness, and revelling in their power to inflict sexual humiliation and abuse with impunity. Fabiana Piccioli brilliantly recreates the chiaroscuro contrasts but it’s the darkness not the light that dominates. Then, there’s the Duke’s callous commodification of women, as reflected in the line-ups in the opening scenes of real flesh on offer, and in the stage-sweeping painted bodies for the aristocratic connoisseur’s voyeuristic collection. Titian’s Venus of Urbino and Rape of Europa, in their gilded frames, seem to ridicule Gilda when she too lies prone in her tiny bedroom, viewed through a small undistinguished window frame. The courtiers’ pantomimes – brutish displays by an unsavoury band of brothers – are choreographed to predatory perfection, unforgiving and unforgivable.

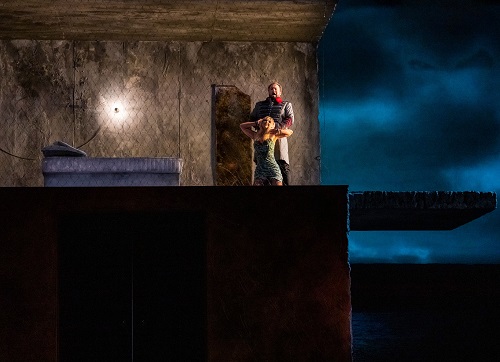

When I saw the first run of the production, back in 2021 (review), I was uplifted by the fact that we were back in an opera house at all as much as by the undoubtedly theatrical coups of Mears’ staging. But, on this occasion (revival director, Danielle Urbas) the dramatic set pieces of the opening few scenes seemed to create energy and expectations that were not subsequently fulfilled. In later scenes, the stage often felt sparse and bare, and visual posing was not an entirely satisfying substitute for genuine kinetic dynamism. The Act 3 quartet suffers musically and dramatically in this production because the two pairs of singers – the Duke and Maddalena simulating sex above, Rigoletto and Gilda facing the audience from a corner of the stage below – are so detached from each other: how can Gilda be shocked by what she sees when she’s not looking? Moreover, Verdi’s contrapuntal and formal deftness thus doesn’t really make its mark.

In the pit, conductor Julia Jones made the score punch hard and heartlessly, but the moments of sensuality and warmth – the father-daughter intimacies, for example – were lacking. Tempi didn’t always feel as if they were serving the dramatic impetus. The cast were good but not breath-takingly so. Stefan Pop’s Duke strutted and swaggered, and sang loudly, with the ‘ping’ in the all the right places, but he was hard and horrid – and heartless, musically and dramatically: a sadist not a sensualist. Perhaps this is what Mears intends. Those gilded horns that this Duke dons in Caravaggio’s allegory really are the mark of the devil. That Gilda falls for his diabolical cult of self-serving sexual gratification, makes her, in this production, less rather than more sympathetic. I found myself recalling those moments in Othello when one just wants to scream at Desdemona, “What on earth are you thinking, doing, saying?”

Not that Pretty Yende didn’t deliver the vocal goods as Gilda. There was much singing of real beauty and sensitivity here. ‘Caro nome’ spun its lyrical and coloratura flights exquisitely – with purity and gentleness. And, vocally, Gilda’s fraught but highly love-fuelled relationship with her father had all of the impact that her infatuation with the reprobate Duke lacked. It was just a pity that in some of their duets they were staring downstage, rather than looking at each other.

Amartuvshin Enkhbat’s jester was, by turns, dissipated and desolate, furiously vengeful and fragilely distraught. At all times, his baritone burned with emotion, and his phrasing was dramatically intense and nuanced. Against the backdrop of water and sky, in the final moments, his pain was palpable. A rare heart-touching moment in this production. Ramona Zaharia had the measure of Maddalena’s amorality, Giancluca Buratto was a sinisterly silky-toned Sparafucila, and Fabrizio Beggi bellowed vengefully as Monterone. The other small roles were delivered with accomplishment.

A different cast, and conductor, might have made more theatrical and expressive impact, but my impression on this occasion was that Mears’ carefully considered mise en scene weren’t quite enough to convince: the eye was captured, challenged and intrigued, but the heart was left cold.

Claire Seymour

Duke of Mantua – Stefan Pop, Rigoletto – Amartuvshin Enkhbat, Gilda – Pretty Yende, Sparafucile – Gianluca Buratto, Maddalena – Ramona Zaharia, Giovanna – Veena Akama-Makia, Count Monterone – Fabrizio Beggi, Marullo – Grisha Martirosyan, Matteo Borsa – Michael Gibson, Count Ceprano – Jamie Woollard, Countess Ceprano – Amanda Baldwin, Page – Louise Armit, Court Usher – Nigel Cliffe; Director – Oliver Mears, Revival Director – Danielle Urbas, Set Designer – Simon Lima Holdsworth, Costume Designer – Ilona Karas, Lighting Designer – Fabiana Piccioli, Movement Director – Anna Morrissey, Orchestra of the Royal Opera House, Royal Opera Chorus (Chorus Director, William Spaulding).

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; Thursday 12th October 2023.

ABOVE: Armatuvshin Enhkbat (Rigoletto) and Stefan Pop (Duke of Mantua) © ROH 2023. Photo by Tristram Kenton