Even by the standards of Baroque opera, Alcina – Handel’s third, and perhaps greatest and most ingenious operatic adaptation from Ariosto’s epic Orlando furioso – comprises quite an array of deceptions and changing personas among its cast to sustain its fantastical plot. Transmuting the sorcery of Alcina’s island to the make-believe world of the theatre or film is a potentially fruitful idea therefore, as it was, for instance, in Francesco Micheli’s production for Glyndebourne in 2022.

The opposite rather proves to be the case in John Ramster’s interpretation of the opera, however, statically set in a film studio for its entirety, between lights on one side and the white projection sheet on the other, though no filming ever actually occurs. Although it observes the Aristotelian unities of time, space and action, just as the libretto sought to impose on the sprawling episodes of Ariosto’s poem, in this context it’s not even exactly clear what the status of Alcina and her sister Morgana is. As they are stopped in their tracks at the end and put into rough orange overalls, they appear possibly to be backstage staff who have overreached themselves and somehow assumed control of the studio, adopting a series of roles so as to dupe the others in the process. Precisely how and why they do that is not explained, and it turns out at the conclusion that Alcina and Ruggiero are in love anyway, to Bradamante’s disgust.

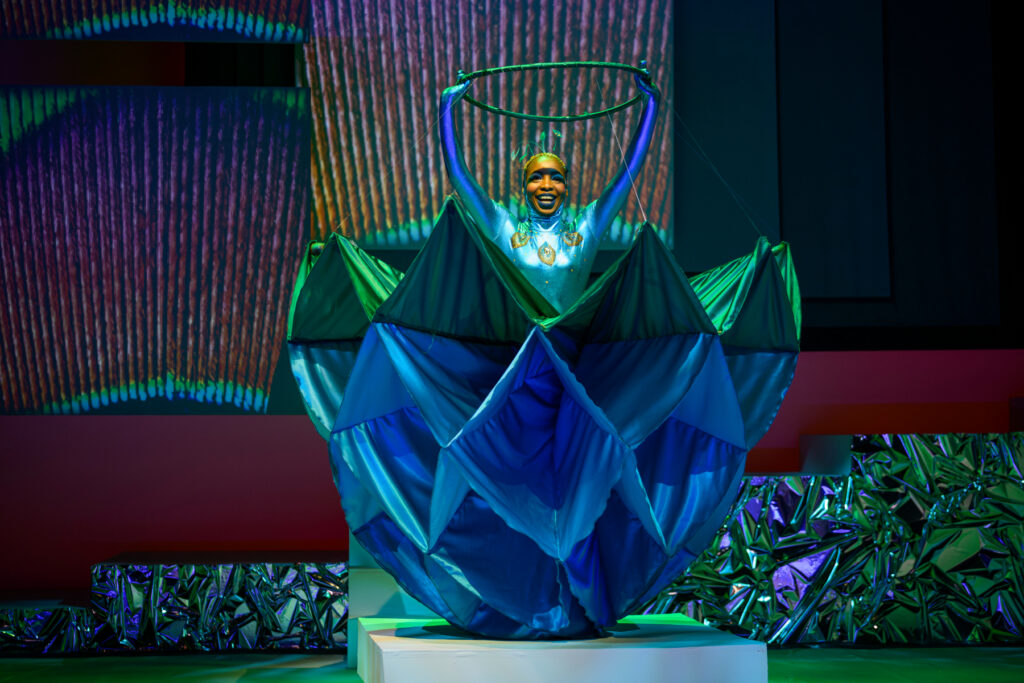

What seems to be a 1970s ethos and some psychedelic graphics in the video projections could have drawn a connection between the power of Alcina’s magic in the original and the hippy predilection for mind-altering substances in that era, but no drug abuse occurs on stage to explain what hold Alcina might suddenly have over those who evidently do become in thrall to her. And despite a formidable array of costumes sported by her and Morgana during the course of three Acts (bizarrely nobody claims responsibility for their design in the programme – only Louis Cover is credited, in general, as the ‘designer’) there is no particular connection between the guises they adopt and the situations they find themselves in, other that they tend to mimic the creatures into which Alcina’s lovers are turned. Morgana, not inappropriately, becomes a preening peacock with a preposterous dress for the flamboyant vocal acrobatics of ‘Tornami a vagheggiar’ as she tries to impress Ricciardo (Bradamante disguised as a man). For all the colour and spectacle on display, and its nimble execution by the singers, the changing succession of dress and painterly daubing on the video projections become a tedious, distracting sequence, offering no insight into the drama at all.

The Guildhall Opera Orchestra are partnered by members of the Academy of Ancient Music, though the ensemble is still relatively slender (3.3.2.2.1 strings) and sound more brittle than poised and lithe. Conductor James Henshaw tends to drive them at a fairly brisk pace, with a sometimes over-forceful continuo. Shana Moron-Caravel gets a raw deal in that respect as Ruggiero, as two of her arias, ‘Mi lusinga il dolce affetto’ and ‘Verdi prati’, are too driven and dominated by the bass line, rather than delicate and refined, prompting her to become overblown in her signing to compensate.

Happily, Georgie Malcolm maintains wonderful control in the title part, finding an ideal range of colour and dynamics to bring out subtlety and variety in Handel’s ever-inventive music for her. As her flighty sister, Morgana, Yolisa Ngwexana brings a suitably vivid flair to her arias, even if her enthusiasm leads her to go a touch sharp at times. Julia Merino gives an unwavering, solid account of Bradamante, Ruggiero’s rightful (or, here, merely first) lover, as constant as her character. Emyr Lloyd Jones is a fervent, perhaps too obtrusive, Oronte, Morgana’s lover (before she takes a fancy to Ricciardo) who is cast here as a cleaner with a frizzy wig, which lends support to the notion that he is a colleague of Morgana and Alcina’s among the menial staff at the film studio, rather than actors themselves.

Alaric Green displays a breezy humour as Melisso, Bradamante’s companion and guide. Samantha Hargreaves is an eloquently innocent Oberto, the boy who searches for his father, Astolfo (another of Alcina’s victims, silent in the opera); even so, the role adds little value to the work, and might as well have been cut as it usually is when staged. Good musical performances overall, then, are expended on a frustratingly inconsequential production.

Curtis Rogers

Alcina

Composer: George Frideric Handel

Libretto: Anonymous, after Ludovico Ariosto’s Orlando furioso

Cast and Production Staff:

Alcina – Georgie Malcolm; Morgana – Yolisa Ngwexana; Oberto – Samantha Hargreaves; Ruggiero – Shana Moron-Caravel; Bradamante – Julia Merino; Oronte – Emyr Lloyd Jones; Melisso – Alaric Green; Astolfo – Harun Tekin

Director – John Ramster; Designer – Louis Carver; Lighting Designer – Andy Purves; Video Designer – Jonathan Strutt; Conductor – James Henshaw, Guildhall Opera Orchestra and Academy of Ancient Music.

Milton Court Theatre, Guildhall School of Music and Drama, London, 3 June 2024

All photos by David Monteith-Hodge.