Well, well, well, Des Moines Metro Opera has done it again.

With their unerringly imaginative and evocative staging of Claude Debussy’s hauntingly lovely masterpiece Pelléas et Mélisande, they have made it impossible for me to ever see it again, lest any future encounter pale in comparison with this singularly stunning artistic achievement.

The cast could not have been bettered. As the titular love couple, soprano Sydney Mancasola and baritone Edward Nelson seemed born to embody these roles. They are youthful, attractive, lithe, and proved to be actors of great depth and nuance. They seem to revel in peeling back the layers of these enigmatic, melancholy, wishful souls who can only be united in death. Moreover, they have a palpable chemistry.

Ms. Mancasola is a local favorite, by virtue of having triumphed in a wide range of assignments in past seasons. The one thing in common in each of her role assumptions is that it is always beautifully served by an unfailingly silvery, limpid, effortlessly produced vocal delivery that ravishes the ear, while her unaffected, sincere acting touches the soul. Her conflicted heroine was heartbreaking in her acceptance of an inexorable fate.

Mr. Nelson was a revelation as a lovable puppy of a Pelléas. The part is very challenging vocally, best served by a baryton-Martin, a lighter flexible instrument that calls for a number of phrases verging on the tenorial. Although making his DMMO debut, he has performed the role before, and it shows. His burnished, gleaming outpouring of languid phrases was matched when called for by his skill at regaling us with impassioned, thrilling outbursts of persuasive presence.

The performance started exceedingly strongly thanks to the peerless Golaud from Brandon Cedel. He began the night with a take-no-prisoners vocalization that set the bar very high indeed, with his buzzy, virile bass-baritone ringing out in the house, providing considerable pleasure. But Mr. Cedel did not just effortlessly encompass the hectoring bully with ease of power. He was also capable of touching vulnerability and carefully judged muted anguish when he modulated his sizable tone to empathetic effect.

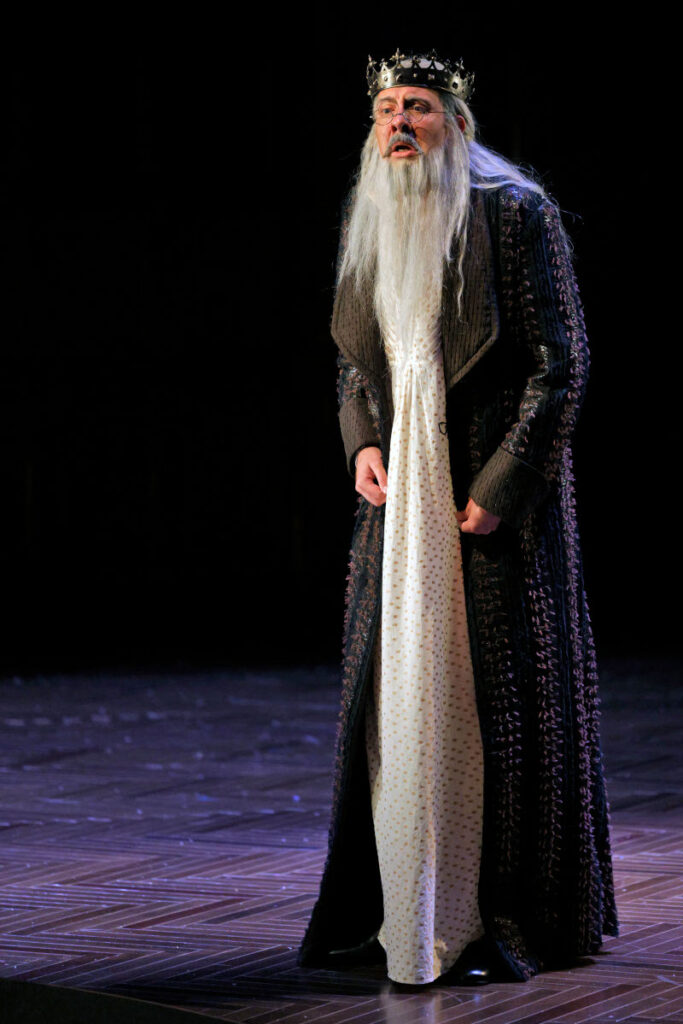

As King Arkel, Matthew Boehler’s regal, portentous, sonorous bass seemed a life force unto itself, a powerful storm of sound that hurricanes might be named after. His physical embodiment of the role was beyond praise. Mr. Boehler is a very tall, imposing man, but when we first see his ailing King, he is severely hunched over, barely able to walk with two canes. As he “recovers,” he methodically gets more upright, until Act V, when he presents himself at his full stature, looking like the towering royalty he is. Masterful.

Mezzo Catherine Martin voiced Geneviève with such assured, mellow eloquence, that I really wished Debussy had given her much more to sing. Her allotted bars of music were a joy to experience, and her poised presence and measured phrases were a perfect calming influence. As the boy Yniold, young Benjamin Bjorland acquitted himself with assured distinction, his well-schooled soprano nailing every phrase with musical accuracy and laudable French.

I have seen Pelléas et Mélisande any number of times in my life, and on many occasions with some internationally starry names. They were all totally eclipsed by this uniformly incandescent cast. But this resounding success was owing to many other elements, including an apparent total alignment of the planets.

In the pit, Derrick Inouye helmed a consummate realization of this moody masterpiece. His vision of the arc of the piece was a rare accomplishment, a perfect marriage of instrumental and vocal unity of purpose. The skilled members of the fine DMMO orchestra responded in kind to Maestro Inouye’s baton, resulting in a first rate revelation of the riches of this ethereal sound palette. The infrequent snarling dramatic outbursts, were made all the more stirring by the almost serene, inevitable unfolding of the lovely undulating phrases that characterize much of the score. Inouye’s attention to solo and ensemble detail was remarkably fine.

It is no secret that I have come to admire Chas Rader-Shieber as one of the industry’s finest stage directors, and his Pelléas only reinforced that reputation. He has conspired with set designer Andrew Boyce to place the staging in a brooding, dark wood-paneled Edwardian drawing room, the massive upstage wall of which is dotted with intermittent lighting sconces. By setting it at the time of opera’s premiere, the pair have created limitless opportunities for creative invention.

Mr. Boyce has risen to the challenge of realizing what is often a gauzy fairy tale, by countering with an astonishing fertile succession of effects. In addition to the imposing, gloomy upstage wall, three murky, earthbound armoires are castered to be able to be moved about the stage. When it all began, with a bare stage, even given the musically excellent beginning, I wondered if I might not tire of the look.

And then the magic soon began. Hidden wall panels would swing open to reveal a brightly lit fantasy forest. A drawer would pull out radiating blazing blue light upward to effect the well water. A deer Golaud bagged was menacingly hung against a blood red panel, waiting to be dressed. The plethora of scenic surprises was a visual embodiment of the “impressions” of the musical style. Best for last (Spoiler Alert). In the final scene, the armoires have been attractively grouped. They open to reveal blinding drifts of snow, the largest of which is the dying girl’s “bed.” Chilling effect in every way.

Jacob A. Climer’s sumptuous costumes perfectly captured the period, and communicated each character’s mind set, and standing in the dramatic relationships. All of this has been lit with consummate skill and ravishing effect by Connie Yun. Brittany V.A. Rappise has provided her usual fine hair and makeup design work, especially for details like the look for Arkel’s beard, that was almost a parallel to Mélisande’s tumbling tresses. And the effect of Golaud brutally dragging around the heroine by her elongated braid only to be abused when he spitefully cuts it off, was visually riveting. But now back to Mr. Rader-Shieber.

There was no moment of this beautiful realization that was not invested with honesty and dramatic purpose. Together with this highly capable cast, he knit together a menacing journey to the unknown, with parallel subtexts of simmering violence and denied intimacy, so compelling that it was impossible to look away from.

The aching crescendo of the title couple’s evolving love built and built until it paused, for a hushed and meticulously paced exchange of “I love you’s,” during which the enrapt audience scarcely breathed, it was so right, so profoundly moving. The cat and mouse game that the unhinged Golaud plays with the resigned victim Pelléas, was unerringly achieved (assisted by Combat Director Brian Robertson), a masters class of ebbing tension and release.

From first to last then, this definitive interpretation of Pelléas et Mélisande was such an accomplishment on my first night at the festival, I wondered if the bar had been set impossibly high for the rest of my opera-going weekend. As Rachel would say:

Watch this space.

James Sohre

Pelléas et Mélisande

Music and Libretto by Claude Debussy

Adapted from the play Maurice Maeterlinck

Cast and production staff:

Golaud: Brandon Cedel; Mélisande: Sydney Mancasola; Geneviève: Catherine Martin; Arkel: Matt Boehler; Pelléas: Edward Nelson; Yniold: Benjamin Bjorkland; Physician: Alan Wiliams; Conductor: Derrick Inouye; Stage Director: Chas Rader-Shieber; Scenic Designer: Andrew Boyce; Costume Designer: Jacob A. Climer; Lighting Designer: Connie Yun; Makeup/Hair Designer: Brittany V.A. Rappise; Combat Director: Brian Robertson; Chorus Director: Lisa Hasson

Top image: Sydney Mancasola as Mélisande and Edward Nelson as Pelléas.

All photos by Cory Weaver.