The rich, vivid score, and dramatic – even sensational and violent – scenario of Puccini’s last opera (not quite complete at his death exactly one hundred years ago, in 1924) are such that its elements of fantasy and spectacle generally feel all too real on the stage, especially when rendered in extravagant, colourful settings (even if increasingly not so overtly Orientalist ones, to draw the opera away from the charge of a condescending vision of ancient China). In emphasising the explicit setting of the libretto in ‘Beijing, in the time of fairy tales’ however, Cecilia Ligorio’s production of Turandot for La Fenice somewhat downplays that aura of easy sensual immediacy, and more consciously brings out the opera’s psychological subtexts.

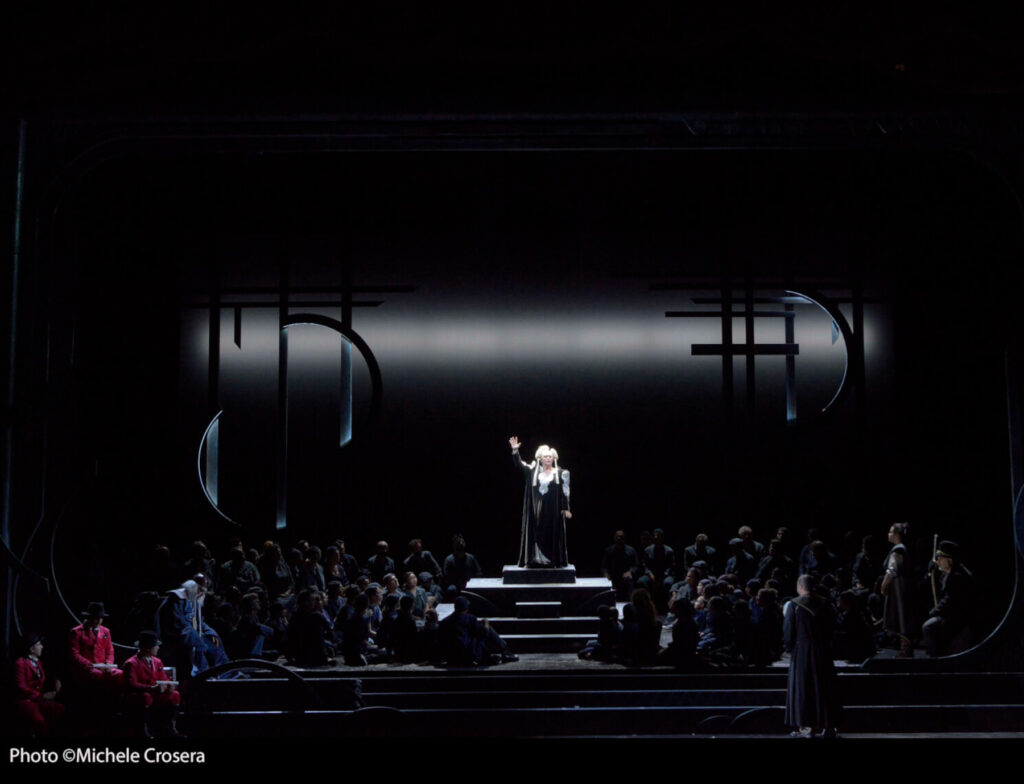

The drama is presented within its own frame on the stage to underline that sense of retelling a fantastical story or myth, and the characters of imperial China are perhaps more like archetypes than ordinary human persons: Turandot first appears (like a vision) high up on a suspended walkway over the stage, and her father, the Emperor Altoum, from the back onto a dais. Calaf stands outside of that frame, as though entering the timeless realm of the subconscious from the world of everyday time, while his captured father, Timur and his assistant, Liù, navigate the space in between, as also do the ministers, Ping, Pang, and Pong from the further side of the Chinese court. Those three make that especially clear by stepping out of the frame in a Brechtian alienation manoeuvre, and more or less address the audience directly in a hearty rendition of their trio, imagining the quieter life they could lead outside of court without jackets on and in a more relaxed mood, almost like vaudeville artists.

The trajectory from darkness to light – or from violence, fear, and death, to life and love – is strongly sustained in Fabio Barettin’s lighting for the production, which moves from foreboding twilight to blazing day. The scimitar shape of the crescent moon plummets from the sky, to serve as the implied method of the Prince of Persia’s execution when he fails to solve Turandot’s riddles, and is eventually replaced by the round disc of the orange sun at the triumphant climax of Act Three.

Saoia Hernández’s Turandot commands a wide range of dynamic and vocal expression, opening her monologue which recalls the rape of her ancestor and her need to ward off casual suitors with a strikingly cool, objective recounting of the past, but developing in passion and rage with the flexibility of a spinto soprano. However, she remains firmly in bolder, dramatic character subsequently in Acts Two and Three, asserting herself as vividly over the orchestra as she first appeared over the stage. Roberto Aronica gives a somewhat gritty, hefty account of Calaf rather than a straightforwardly lyrical one, though ‘Nessun dorma’ comes off confidently, expressing little doubt that he will win Turandot round.

Liù can all too easily be characterised as a meek, sacrificial victim, but Selene Zanetti is bold and assertive, starting with wide vibrato for ‘Signor, ascolta’; although that settles down, her performance is still marked by an outward, candid fervour. By contrast Michele Pertusi is a careworn Timur, and Marcello Nardis expresses on Althoum’s part a certain weariness with the destruction that Turandot’s frigidness brings about, and a slight nasal drawl which underlines the sinister nature of her oath.

If the production explores something more of the interior processes and motivations at work within the drama, then Francesco Ivan Ciampa’s performance with the Chorus and Orchestra of La Fenice is certainly vigorous and determined. The nervous, restless opening evokes the increasing anxiety of those at the Chinese court, after which each incident is incisively conveyed in the music, both by the forceful Chorus or the colouristic detail of the instrumental playing. The latter is often expressionistic in its immediacy, whether that is in dramatic outbursts for full orchestra, whining violin sighs, or yearning clarinets, contrasting with a softer, impressionistic wash of sound – especially by the strings – in more tender passages. The boldness of the musical performance (using the standard completion by Franco Alfano) complements the subtler interpretation of the drama itself to make this a well-rounded, thoughtful and less lurid account of this heady fairy tale.

Curtis Rogers

Turandot

Composer: Giacomo Puccini

Libretto: Giuseppe Adami and Renato Simoni

Cast and production details:

Turandot – Saoia Hernández; Altoum – Marcello Nardis; Timur – Michele Pertusi; Calaf – Roberto Aronica; Liù – Selene Zanetti; Ping – Simone Alberghini; Pang – Valentino Buzza; Pong – Paolo Antognetti; A Mandarin – Armando Gabba; Prince of Persia – Massimo Squizzato

Director – Cecilia Ligorio; Designer – Alessia Colosso; Costumes – Simone Valsecchi; Lighting Designer – Fabio Barettin; Conductor – Francesco Ivan Ciampa; La Fenice Chorus and Orchestra

La Fenice, Venice, Italy, 18 September 2024

All photos by Michele Crosera/La Fenice