Interested in operas that have rarely if ever traveled beyond their linguistic or ethnic homeland? You may well be delighted to get to know this Romantic-era work by the Swedish composer Per August Ölander. Ölander (1824-86) was taught largely by his father (a music teacher) and by Johan Erik Nordblom, organist and music director at the cathedral in Uppsala. He learned enough to become a highly competent violinist, a music critic, and a composer of works in many different genres. In a land that still had far fewer musical institutions (e.g., opera theaters) than, say, Belgium or Poland, Ölander supported himself, rather like Borodin, by a “worldly” job—in his case, as a customs official. (His Symphony in E-flat was recorded back in the 1990s.)

Blenda, the first of Ölander’s two operas, was given its premiere at the Royal Opera in Stockholm in 1876 and remained in the repertory there for a few years. His other opera, a lighter work, ended up having a longer life in Swedish theaters.

I’d never heard any music by Ölander before. It is well crafted and engaging. True, it tends to fall into four-bar phrases, but so does the music of lots of nineteenth-century operas other than Wagner’s. Ölander’s style sounds, to my ears, like a mixture of Italian opera of fifty years earlier (Rossini and Bellini, but without the coloratura) and some of the more conservative elements of the Austro-German conservatory norm, indebted as that was to Mendelssohn and Schumann. The work sometimes gains a “popular” quality through regularly phrased folklike tunes (in the manner of Weber’s Der Freischütz), e.g., King Sverker’s “I want to rule my realm in wisdom and peace” (Act 1). An evocative Grieg-like passage introduces us to Blenda’s forest retreat at the beginning of Act 3. There are also dramatically apposite horn calls at various points. All in all, the score conveys much comfortable coziness and conventionality, even when the plot takes a dramatic turn.

Said to have been modeled at least somewhat on Schiller’s drama about Joan of Arc (The Maid of Orléans), Blenda takes place in Sweden, under a King Sverker: apparently Sverker I, who ruled in the twelfth century and had to deal with threatened invasions by the Danes. The librettists have given the heroine the name Blenda, clearly in honor of the ninth-century folk-heroic figure who was said to have led a troop of warrior-maidens from rural Vàrend (in Småland) to entertain the Danish invaders and then slaughter them in their sleep. The early Blenda chroniclers may have been thinking in part of the biblical Jael and Judith, who likewise slayed the unwary enemy. They report (surprisingly to us non-Scandinavians) that the Geatish King Alle, in gratitude, rewarded Swedish women with many rights, e.g., ones relating to inheritance.

The booklet-essay doesn’t explain any of this background, perhaps assuming that we all know about Swedish history and myth, whether from primary sources (e.g., Johan Stiernhöök and Snorri Sturlusson) or from versions reworked for nineteenth-century readers by poets and historians with a romanticizing bent. My guess is that the librettists chose to invoke the ninth-century Blenda by giving the heroine that name and by surrounding her by, yes, a chorus of patriotic maidens from Värend.

Briefly, the plot enacts a war of national liberation by the Swedes against the more powerful Danes. The trouble-making Swedish royal prince Johan has set tempers flaring by abducting a Danish noblewoman. (The actual Prince Johan did this and worse under Sverker I.) He also expresses disdain for any women attempting to fight in the Swedish army, much less lead it. Several Danish men take diverse positions regarding the advisability of pursuing the war. And at the center of all this is the bold Blenda, who at one point grabs a sword and (Joan-like) leads the troops against the invaders.

As in some better-known operas (e.g., Ernani), here a sole female character (not counting the female choristers) is consistently surrounded by males, several of whom desire her or try to manipulate and control her. The Evil Guy tenor (Johan) ends up being stoned to death by the enraged Swedish crowd (again, this has some historical basis), and the Good Gal soprano (Blenda) is accidentally stabbed to death by the Good Guy tenor (Harald), who was aiming at the Danish general (Dotta). Blenda’s sad end then becomes the occasion or excuse for the two nations to put rancor aside and declare peace.

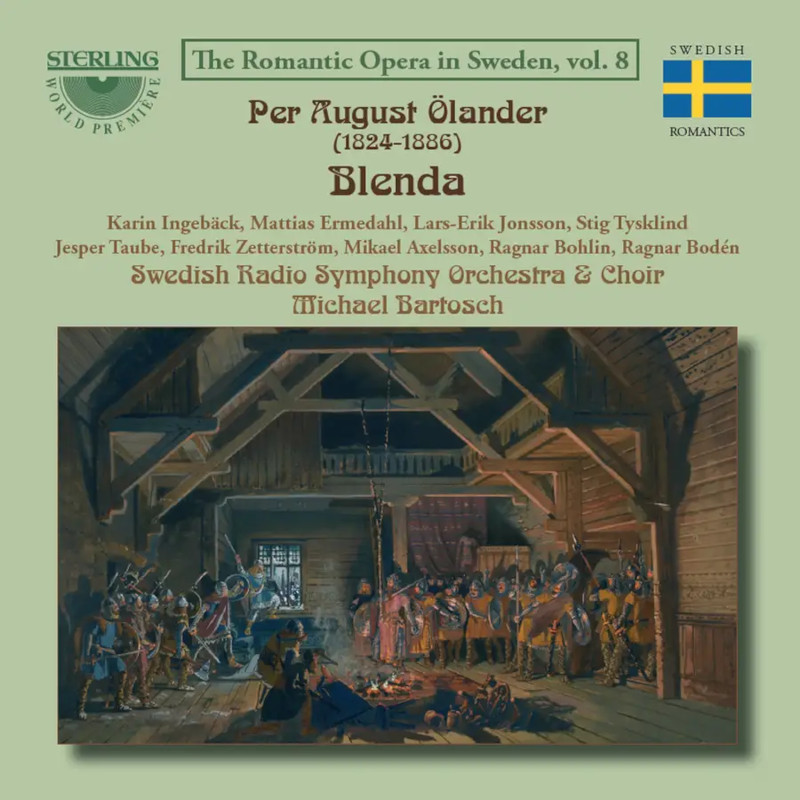

I can imagine Blenda making a powerful effect in Sweden, where audience members have read about the plot’s historical and mythical elements in their schoolbooks and have seen the Swedish heroes and heroines represented in canvases and book illustrations. (The “Blenda” entry in Wikipedia includes a nineteenth-century painting of the mythico-historical heroine and her troop of nervy, patriotic women.) Even though I did not have that kind of lifelong preparation, I ended up feeling involved in the risky adventures of this principled and courageous young woman. I was also intrigued by the end of Act 3, where the spirits of warrior maidens who had recently died in the Blenda-led battle against the Danes accuse Johan of being “the author of our sorrow.”

The recording was made in 1997 in the Berwald Hall in Stockholm. It is here released, or re-released, as vol. 8 of the series “The Romantic Opera in Sweden”. The sound is clear and balanced; the performances, expert and idiomatic. I can’t fully separate my enjoyment of the piece from my enjoyment of the highly proficient and musicianly performance. Best of all is Karin Igebäck as Blenda, her tone pure and clear as a mountain stream. She makes no attempt at beefing up the sound to give it more muscularity, and the portrayal is all the more magical (or perhaps mythical) as a result. The chorus and orchestra handle everything with high skill, and Michael Bartosch phrases with naturalness and keen dramatic intent.

I particularly appreciated hearing, from the entire cast, those closed vowels that lovers of Swedish films know well and that (to my Swedish-ignorant ears) lend darkness and emotional reserve to anything that is said or sung. My positive reaction is surely heightened by the recording’s booklets, containing an informative though too-short essay, plus the libretto in Swedish and something approaching English.

If that last remark sounds like a gripe, you’re right. The translations are often marred by typos, mistranslations, and unidiomatic usage. “Blended” should be “blinded,” “trough-composed” (in a pigsty?) should of course be “through-composed”, and we read of characters engaging in “fiercely fights.” The “Choir [i.e., Chorus] of the People” cries out, weirdly, “There is a soldier, who threaten us with feud!”

The essay huffs and puffs about how much the opera’s music does or does not reflect nationalistic and Wagnerian trends in matters of musical style. Better to admit that the work is what it is: an earnest attempt, in the mainstream musical language of the day, at putting patriotism—and a kind of proto-feminism—on stage, and one that, at least on this recording, succeeds.

A good singing translation would enable Blenda to be performed by, say, opera studios at high-level conservatories or music schools. (Perhaps in some midwestern state that has a lot of people of Scandinavian descent?) The work would bring much pleasure and enlightenment, especially if preceded by a good lecture about early Swedish history and its many retellings. For more info on the quirky history of the recording (which was made in sessions across four years, 1997-2000) and sat unreleased until 2019, click here.

Ralph P. Locke

Blenda

Composed by Per August Ölander

Libretto by Ludvig Josephson

Karin Igebäck (Blenda), Mattias Ermedahl (Harald), Lars-Erik Jonsson (Prince Johan), Jesper Taube (King Sverker), Fredrik Zetterstrôm (Nils Dotta), Stig Tysklind (Cardinal).

Swedish Radio Symphony and Choir, cond. Michael Bartosch.

Sterling 1118-19 [2 CDs] 136 minutes.

Click here to order or to try any track.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music and Senior Editor of the Eastman Studies in Music book series (University of Rochester Press), which has published over 200 titles over the past thirty years. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, The Boston Musical Intelligencer, and Classical Voice North America (the journal of the Music Critics Association of North America). His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and is included here, lightly revised, by kind permission.

Top image: Blenda by August Malmström (1829-1901) courtesy of Wikipedia