To say Glyndebourne and Le nozze di Figaro are linked is a huge understatement: it was Mozart’s opera, which many see to be the most perfect ever constructed, that launched that great institution in 1934; that cast included Heddle Nash as Don Basilio and Willi Domgraf-Fassbaender as the Count. And who can forget Vittorio Gui’s recorded performance with the Glyndebourne Festival Chorus and Orchestra from Abbey Road in July 1955; the cast there included Sesto Bruscantini and Sena Jurinac (and the much-loved Ian Wallace as Bartolo); the performances with that cast at Glyndebourne itself took place in June of that year.

The Glyndebourne Prom is always a special night, productions pared down for the Albert Hall stage. This was the eleventh semi-staged performance of Figaro at the Proms: all from Glyndebourne, starting in 1963 (Varviso). The most recent, like this occasion, featured the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, but conducted on that occasion by Robin Ticciati (Vito Priante as a characterful Figaro, Sally Matthews as the Countess and Isabel Leonard as an unforgettable Cherubino). In between the first Proms performance and today, luminaries such as Haitink and Rattle have bought their thoughts (Rattle was the first to bring a period instrument band, as here, the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment).

No wonder the place was packed to the rafters. And it was an evening of surprises (not least being told it was estimated to finish at 22.20 after an 18.30 start: it actually finished nearer 10pm). But maybe that misdirection was fate saying there were tempo surprises ahead. Conductor Riccardo Minasi has clearly rethought the score in light of scholarship, or at least one hopes so; there was rubato here, for example. But not rubato one might encounter in Tchaikovsky, more one gleaned as an extension from Affektenlehre and directly related to the theory of rhetoric. I had hoped for an explicatory essay, perhaps references to Johann Matheson and Mozart’s extension of Baroque aesthetic within a Classical orbit, but no (and apparently nothing in the Glyders booklet either). The closest parallel I know to what I heard on stage is the Narratio Quartets recent cycle of Beethoven String Quartets on Challenge Classics; but the Narratio seem more immersed in their chosen composer, and so are completely convincing. That cycle will change the way many people hear Beethoven. With Minasi, there were raised eyebrows aplenty, but revelations from any sort of ‘Above,’ there were few. ‘Sull’aria’ lurched around curiously, slowly, as if sea-sick, but in slow motion.

The OAE was on top form, of that there was no doubt, following Minasi’s relaxings into new phrases like a hawk, offering punchy timpani and brass (the horns were exceptional throughout the evening: Gavin Edwards and David Bentley). Mathew Fletcher’s harpsichord continuo was stunningly imaginative (playing an instrument that at least in the hall was so deep-toned it could have been a fortepiano) Woodwind added turns and decorations on repetitions of material (much like a singer might in the A1 section of an aria). The final succession of chords in the Overture before the coda were highly emphasized, and definitely slower than the prevailing tempo; effective at the time, but how convincing is it, really?

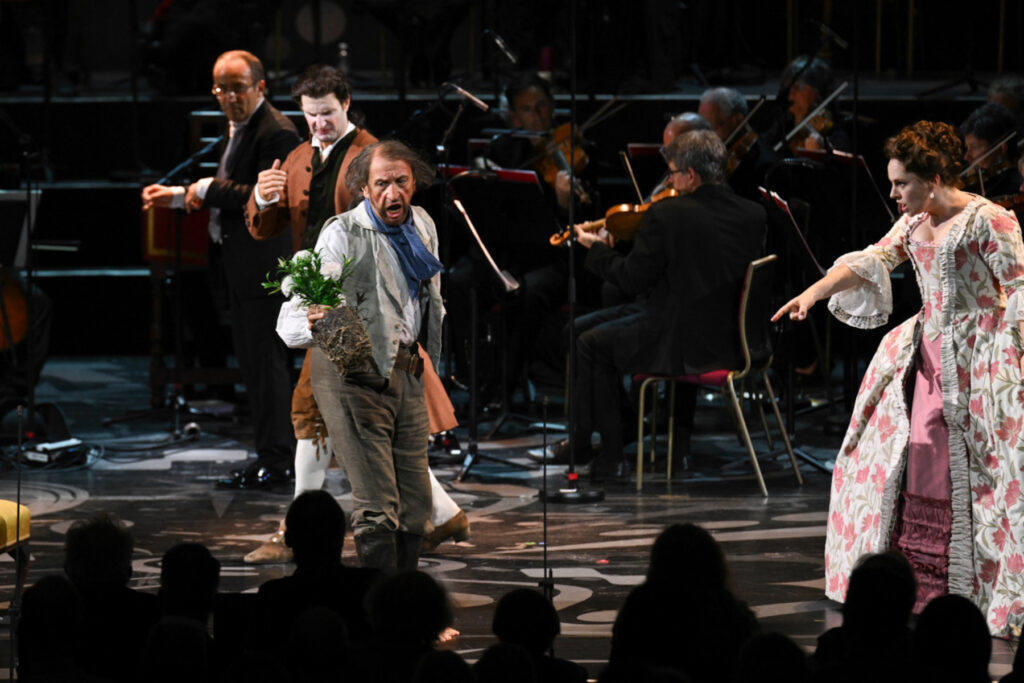

The stage held minimal props: a screen and a chair to begin with, augmented later by a bath. The Glyndebourne production was directed by Marianne Clément; the adaptation for the Albert Hall was by Talia Stern, who used the stage well (both in front of and behind the orchestra – plus a nice acknowledgement at one point of Sir Henry’s bust). And there was a nice game involving reducing numbers of chairs later on. But paring the production to its basics puts the onus on the singers and their acting. Prety much across the board, the cast rose to the challenge, sometimes stunningly so.

Where to start with the cast? Those who impressed the most should be first though the door, so step forward Adèle Charvet. She is a regular at Versailles, her Giulietta (Zingarelli’s Giulietta e Romeo; yes, that’s ‘Juliet and Romeo’) a highlight. If Sarah Leonard was luxury casting last time around, Charvet was equally if not more stunning, her mezzo miraculously rich and expressive. She plays a trouser role of course – a female playing male who here at one point has to dress as a female. Gender fluidity ain’t new, kids. Charvet’s act 2 ”Voi che sapete” was a model of phrasing and perfect interaction with the OAE woodwinds.

Alessandro Corbelli has been around for a long time (his Sulpice La fille du régiment particularly memorable) and still dominates the stage. His “La vendetta” was a masterclass in acting and characterization (the bravos from the audience immediately after fully justified). Add to this the Countess of Louise Alder, her second act ‘Porgi amor’ sung from the heart, her third act ’Dove sono’ shot through with poignant regret. How well she interacted, too, with her Susanna, a singer new to me live, Swedish soprano Johanna Wallroth (who represented her home country at the 2023 BBC Cardiff Singer of the World and who is a BBC Radio 3 New Generation Artist, 2023-25). Wallroth reveled in the role, her interactions (yes with the Countess, but also Figaro) alive at each and every moment.

All of the smaller roles were well taken: Alexander Vassiliev was particularly noteworthy as Antonio, very funny in his inebriation, and the simply stunning Barbarina of Canadian soprano Elisabeth Boudreault stood out, elevating her character to far more than a one-aria role (the ‘Pin’ aria was wonderful, though, her agitation palpable). Madeleine Shaw was an imposing Marcellina, adapting her voice nicely to Mozart (she impressed previously as the Abbess in ENO’s Suor Angelica in September 2024; her roles elsewhere include Wellgunde and Fricka). Vincent Ordonneau and Robert Forrest made the most of Don Curzio and Don Basilio, respectively.

Which leaves the Count, and Figaro himself. Huw Montague Rendall was a testosterone-driven Count, brutish often, and clearly wanting his own way. No wonder he bought back the droigt du seigneur. The last performance of Figaro I saw at Glyndebourne was marred by a botched request for forgiveness to the countess; not here, it regained its status as one of the most ravishing, heartfelt moments in music (even if the Countess’ instant forgiveness does rather stretch credulity). Montague Rendall’s debut album, Contemplation (which includes a Papagena from another singer this evening, Elisabeth Boudreault, is well worth seeking out). As Figaro, Tommaso Barea seemed to warm into the evening somewhat, but his overall characterization was multi-dimensional, his comic timing good. Perhaps his act 4 aria ’Aprite un po’ quegl’ occhi’ was, along with that request for pardon, his finest moment, more animated than many readings of this aria.

There is a ’child’ too, played by Pippa Baton, a directorial sleight that perhaps refers to a wish from the Countess for children?

This was not a ‘complete’ Figaro; but is there such a thing, anyway? Interpretatively, it raises many questions, and that’s a good thing. And I shall be keeping my eyes peeled for Boudreault, for sure.

Colin Clarke

‘The Marriage of Figaro’ from Glyndebourne (BBC Proms 2025)

Le nozze di Figaro

Composer: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Libretto: Lorenzo da Ponte

Cast and production staff:

Figaro – Tommaso Barea; Susanna – Johanna Wallroth; Count Almaviva – Huw Montague Rendall; Countess Almaviva – Louise Alder; Bartolo – Alessandro Corbelli; Marcellina – Madeleine Shaw; Cherubino – Adèle Charvet; Don Basilio – Robert Forrest; Barbarina – Elisabeth Boudreault; Antonio – Alexander Vassiliev; Don Curzio – Vincent Ordonneau; First Bridesmaid – Sophie Sparrow; Second Bridesmaid – Biqing Zhang; Child – Pippa Barton

Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment; Conductor – Riccardo Manasi; Director – Talia Stern (based on the 2025 Glyndebourne Festival production directed by Marianna Clément)

Royal Albert Hall, London, 27 August 2025

All photos © Chris Christodoulou