The astonishing young tenor Taylor Stayton anchored the overall vocal excellence with an effortless traversal of the title role. Time was when the vocal demands of this opus limited any production attempts to the occasional appearance of someone like Rockwell Blake who could make at least a decent stab at the Count. These days, high-flying tenors seem to be turning up with happy regularity, and with his performance here, Mr. Stayton has announced that he is deserving to be numbered on the short list of Rossini all-stars.

The voice has it all: flexibility, endurance, beauty of tone, generosity of substance, and stratospheric range. Moreover, Taylor cuts a handsome figure on the stage, appealing, spontaneous, and boyishly athletic (witness a surprising – planned – fall into a clean somersault when he got tangled in his newly-donned hermit robes). He has already appeared at such top tier houses as the Met, and will undoubtedly become a regular fixture there and elsewhere. JDF should be very very nervous!

Sydney Mancasola (Countess), Taylor Stayton (Ory) Stephanie Lauricella (Isolier)

Sydney Mancasola (Countess), Taylor Stayton (Ory) Stephanie Lauricella (Isolier)

Every inch his equal, rising star Sydney Mancasola offered cascades of spot-on vocalizing as the Countess Adele. The silvery soprano seemed to gain in heft after her spectacularly sung entrance aria, and her immaculate coloratura was matched by her poised stage presence. In addition to meeting every challenge of some of Rossini’s most difficult ornamentations, Ms. Mancasola admirably acted with her voice which, in a comedy, is to say she found myriad ways to be funny. The inspired, heaving sobs that she injected into her “weeping” moments were worthy of Carol Burnett. This was just one of many memorable vocal effects. Having recently seen the uniquely gifted Cecilia Bartoli in this punishing role, I can say that Ms. Mancasola found an equally effective vocal identity as Adele, and lavished the part with dazzling pyrotechnics.

As the page Isolier, Stephanie Lauricella was a delectable puppy dog, believably boyish, and possessed of a robust mezzo that nonetheless had amazing dexterity, sort of an impish Cherubino on uppers. She strode around the space with understated masculinity, modulated her “handsome” putty face into an endless variety of fretting takes and wide-eyed surprises, and milked being a woman-playing-a-man-playing-a-woman for all it was worth. Best of all, Ms. Lauricella was up to the same high standards as her co-stars, making the well known bedroom trio an unfolding delight, musically and comically.

Iowan Wayne Tigges made a welcome debut here on home turf with a big voiced at-but-not-over the top traversal of the Tutor. Mr. Tigges seemed to roll up Mustafa, Bartolo, and Basilio, chewed on them for a bit, and then spit out a characterization of laser-beam intensity, his imposing bass bouncing happily through the house. But Mr. Tigges’ voice was not just imposing. When called upon, he could vocally dance around rapid-fire patter with the fleet-footed skill of a prize fighter. Stephen Labrie also had good luck with the featured role of Raimbaud, his full-bodied baritone proving to have warm appeal. He tickled us with his assured drinking song, although when he pressed the patter too hard, he occasionally got ahead of the beat. Since his voice carries well in the house, I would urge him to put a little less effort into “selling” those effects. Margaret Lattimore was luxury casting as Ragonde, her plummy mezzo as rich as chocolate mousse. An added bonus is that Ms. Lattimore has perfectly tuned comic timing and her many subtle bits of registering dismay never failed to elicit a laugh.

Chorus Master Lisa Hasson’s well-schooled ensemble proved to be such an important element that there is no doubt it was another major ‘character’ in the successful telling of the story. Well-choreographed movement, including a meticulous execution of the sewing scene with goofy synchronized, audible stabs at the embroidery hoops, just kept growing in effect and finally all this precision gave way to great abandon in the drunken nun scene.

Howard Tsvi Kaplan’s lavish, colorful costumes would not be out of place in Once Upon a Mattress, and I enjoyed set designer R. Keith Brumley’s Disney-inspired castle and drawbridge, and the too too pretty, have-a-nice-day sun, that got comically clouded with a cut-out whenever someone had the sadz. Barry Steele’s clever lighting conspired gleefully with all the visual shenanigans. The effect of the massive bed rising from the depths of the apron was well-calculated (does even fracking go as deep as that trap?).

If you were seated on the front side of the thrust stage, the direction and blocking was quite inventive, but I may not have been as happy to see the show from the sides. Most of the communication to the audience was played straight out. Still, David Gately devised fresh and funny business, crafted varied movement, and infused the final bedroom trio with a tasteful physicality.

In the pit, Maestro Dean Williamson’s orchestra was, well, why beat around the bush, just about as good as it gets. The scattered effects of the prelude were well judged and the rhythmic control and overall crescendo effects were meticulously coordinated so as to sound spontaneous and inevitable. I actually may have erred in comparing this to Pesaro. Based on my one experience with that annual Rossini Festival, this Le Comte Ory was far superior. Italy may have something they could learn from Indianola.

Everyone involved with the powerhouse production of Dead Man Walking covered themselves in glory. This was music- and theatre-making of the highest order.

Composer Jake Heggie has made the pivotal role of Sister Helen Prejean a huge ‘sing.’ It ranges from simple, floated folk tunes, to urgent conversational exchanges, to pointed wisecracks, to punishing emotional outbursts, to stinging dramatic force required at both extremes of the range. Librettist Terence McNally has compounded the challenge by scripting a torturous emotional journey that requires elements of extreme restraint, steady growth to understanding, and utter abandon to a raw transformation and spiritual bonding. In Elise Quagliata, the creators may have found their most powerful Helen yet.

Her luminous voice made every moment count, with a powerful, tireless mezzo displaying a rich, amiable tone of unbelievable stamina. Ms. Quagliata could hurl out climax after climax, one topping the other for searing intensity, then just as easily she could turn on a dime and scale back to a haunting whisper. The palette of vocal color Elise brought to the drama was staggering, from the sunlit joy of the opening scene to the final unaccompanied lines, mere wisps laced with unconditional love after Joe’s execution. This was great vocalism with limp, effortless delivery that was always deployed in committed service to the character. Truly memorable.

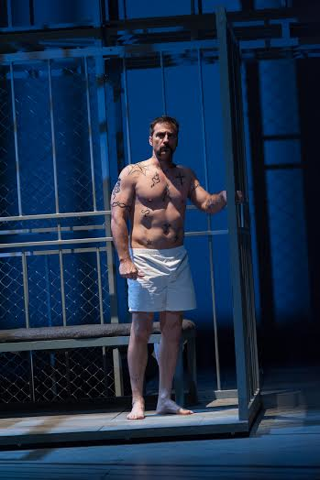

David Adam Moore as Joseph de Rocher

David Adam Moore as Joseph de Rocher

As the murderer Joseph de Rocher, David Adam Moore is also now surely without equal in this part. Mr. Moore discovered every possibility to transform this character who has committed a despicable crime into a complex entity that was dramatically and musically compelling. It did not hurt that he possesses a gorgeous, forceful baritone with a sound technique that not only served the spirited (often coarse) declamations well, but also facilitated heart-rending messa da voce effects. The baritone took us on a fascinating aural and physical voyage to repentance. When he finally broke down and confessed, it was cataclysmic, a life changing moment for both character and audience. As the repentant killer, he tore us apart in his final moments. David was physically perfect for de Rocher, theatrically affecting, musically impeccable, and fully deserving of the most vociferous and robust ovation of the entire festival.

After her merry hijinks in the Rossini, the versatile Margaret Lattimore was back as Joe’s grieving mother. On this occasion, Ms. Lattimore brought seamless beauty to her singing, and elicited wondrous empathy for her plight. Although appearing as simple, unaffected, and homey as a Wal-Mart shopper, she engendered a noble strength of character. Her steadfast dedication to all her sons’ well-being informed the piece, and made us seriously question whether it is moral to kill a killer who is also a big brother, loving son, and troubled child of God. As the unsympathetic and garrulous prison chaplain, Stephen Sanders put his steely, forthright tenor to good purpose in portraying an unyielding personality. Kyle Albertson found a good solution to make the Warden three-dimensional by alternating his stern, firm-voiced statements with mellifluous phrases as appropriate.

Wayne Tigges also did a remarkable about face from daffy Rossini business, to contribute a superb turn as the father who retreats from his vengeful feelings into a miasma of doubt and spiritual indecision. His nuanced singing was another highlight of the day. Karen Slack (Sister Rose) captured the audience with a spinning, thrilling top voice that soared above the staff. Ms. Slack’s distinguished work in the extended, sonorous duet with Helen, served notice that she is an artist we will definitely want to hear again (and again).

The final ensemble

The final ensemble

R. Keith Brumley has designed a scenic environment that is sparse, fragmentary, and so highly effective that you almost didn’t notice it. Set changes were accomplished with speed and minimal effort. Barry Steele provided a moody, often stark lighting design with many splendid effects, like the blood red wash as the execution party sway-marched to the chamber. Fort Worth Opera’s simple costume plot did all that was needed. That company also furnished an integral sound design that brought the piece to a chilling conclusion with the whooshing release of poisonous liquids and the beating heart monitor that pierced the theatre until it beat no more.

Conductor David Neely led an immaculate reading of this challenging score. From the meandering phrases of the opening prelude, through the tense confrontations that proliferate the piece, to the gut-wrenching anguish of the many extended ariosos and ensemble, Maestro Neely allowed the score to unfold with both sensitivity and tension. Arguably the most profound and forceful musical moment was the slow, forceful unfolding of the “Our Father” peppered with cries of “Dead Man Walking” by the whole company as the tension built to the unavoidable moment of punishment. The orchestra has never sounded more committed, singly and in ensemble.

Director Kristine Mcintyre not only honed dramatic moments of unerring dramatic accuracy, but also mined every ounce of humor in the work, striking a powerful balance. She managed to help each performer find a sympathetic core to the character. Finally, the venue itself was perhaps the most perfect space imaginable to invest the work with such soul-stirring impact. Unlike proscenium productions, where we are observers from the other side of the pit, in this thrust arrangement we became full participants in the drama. When de Rocher was strapped to the table, suggesting the crucifix, and Helen was onstage reaching out to him from across the divide, we were inexorably drawn into the act of witnessing the loss of a life. As her final unaccompanied hymn tune faded and the lights all went to black, in that moment before we dared break the silence with applause, someone a couple of rows behind me broke out in heaving sobs. I cannot imagine a more powerful production of this engrossing opera.

The new staging of La Traviata included a deluxe physical production, world famous music, an expansive and extravagant concept, unique staging features, and in the Everest of female Verdi roles, a stunning new soprano to cheer to the rafters. Caitlyn Lynch regaled us with a polished, creamy tone of spun gold.

Caitlyn Lynhc (Violetta) and Diego Silva (Alfredo)

Caitlyn Lynhc (Violetta) and Diego Silva (Alfredo)

Fussbudgety operaphiles often like to opine a fine Violetta needs to be Joan Sutherland in Act I, Birgit Nilsson in Act II, Montserrat Caballe in Act III and Beverly Sills in Act IV. Granted, this role is a varied, complicated, fascinating piece of vocal writing, and Mr. Verdi has given Violetta several musical ‘personalities’ to cope with. And Ms. Lynch decidedly showed she had the goods to bring all the requisite big moments to fruition.

Indeed, she proved capable of accurate, playful coloratura; could summon a spinto-ish heft throughout many a rangy phrase; floated high notes with great delicacy; and is blessed with a lovely face and figure. Caitlyn is relatively new to this complex heroine, arguably Verdi’s greatest, but she clearly has abundant stage savvy, has all the notes in her voice, and she concentrates mightily on singing it conscientiously with utmost attention to detail. Time and further outings in the part will no doubt afford this gifted soprano the opportunity to build on this solid beginning and invite more spontaneity. If there is one quality I would urge her to explore, it is a poignant fragility that is not yet readily present in her impersonation. Such emotional investment begins to inform her “Addio dal passato” when she starts to find the right balance of sound technique and touching dramatic intention.

Diego Silva’s medium-sized tenor has a somewhat fast vibrato that found his Alfredo at his best in Act III when he could let it all out. Elsewhere he gambled on crooning his way through too many tender phrases, injecting breathiness to suggest sincerity. As long as Mr. Silva kept the voice hooked up he made a decent impression, but when he let his focus wander, got off the line and went diffuse, he tended to flat especially on descending phrases. Still, he is nice-looking, sincere, and has good musical instincts.

Todd Thomas has a substantial baritone and is capable of a big, imposing sound. Perhaps a bit too imposing. He almost overstated his first entrance, and verged on a caricature of paternal anger that made him come off as a little unhinged. He settled down after a few phrases but never quite found the empathy and conflicted tenderness in the part. Mr. Thomas’ requested embrace of Violetta came off as perfunctory, but so was his relationship with his son. His technique is rock solid, and he seems to be capable of far more sensitive vocalism. Perhaps it was a directorial choice, but he just did not seem spiritually connected to anyone’s plight, even his own.

Ashley Dixon, a smoky-toned Flora, commanded our interest. Luis Orozco, a lanky, egotistic Duphol showed off a solid bass and no nonsense delivery. Brenton Ryan was an appealing Gastone, making the most of his stage time and displaying a pleasantly refined lyric tenor. Tom Dillon seemed luxury casting as Dr. Grenvil, singing with a beautiful, orotund, sympathetic bass.

“Libiamo”

“Libiamo”

As we entered the theatre, a hologram-like projection of a ghostly woman in a wedding dress floated across the black scrim from stage right to disappear stage left, only to keep re-appearing in an endless loop. This was powerful imagery that foretold the journey we were about to undertake. Robert Little’s expansive set design suggested luxury with judicious choices. The ballroom was created with layers of gilt doors and arches that gave great depth to the stage. Here and throughout the evening, the rich look was augmented by gorgeous period costumes from A.T. Jone and Jones, Inc., that were lavish and eye-catching. An expert make up and hair design from Joanne Weaver completed the perfect picture.

The bucolic atmosphere in Act II was also pleasing if arguably a bit too sprawling. Act III gave us a dazzling red Moorish framework. Lisa Hasson’s excellent chorus was well used, first as the wiggling naughty gypsy girls, then as the stalwart toreros with one bullfighter and a boy in a bull mask cavorting, all the while conveying the idea of slightly salacious party games. The gaming table was effectively situated up left but somehow it seemed too inconsequential in size. Kyle Lang’s fluid choreography contributed mightily to the success of the party scenes.

The placement of the giant deathbed on the thrust was a good choice, and the black scrim behind it eventually revealed a row of buildings on the street outside. I quite liked the touch of seeing the singing revelers momentarily people that boulevard, and appreciated the visual of Alfredo standing with his back to us, looking up at Violetta’s window.

Lillian Groag’s direction was chockfull of such imaginative considerations. Her blocking, especially group scenes, used the entire space well with a focus that was beautifully judged so we always knew right where to look. Minor characters were unusually well-developed and sustained. I wish that the three principals had found more sub-text to play so that they might have ignited some real sparks and generated some needed heat. This was exacerbated in the garden scene where the gap between Violetta and Germont was sometimes too great, the crosses too big, the moves occasionally unmotivated.

David Neely led the score with predicable stylistic flair and once past a somewhat scratchy prelude, the sounds emanating from the pit were assured and purposeful. The company has assembled a technically first-rate, beautifully sung mounting of this timeless classic. I only wish they had also found the heart of it.

James Sohre

Le Comte Ory

Le Comte Ory: Taylor Stayton; Comtesse Adele: Sydney Mancasola; Isolier: Stephanie Lauricella; Raimbaud: Stephen Labrie; Ragonde: Margaret Lattimore; Tutor: Wayne Tigges; Alice: Abigail Paschke; Conductor: Dean Williamson; Director: David Gately; Set Design: R. Keith Brumley; Lighting Design: Barry Steele; Costume Design: Howard Tsvi Kaplan; Make Up and Hair Design: Joanne Weaver (for Elsen and Associates, Inc.); Chorus Master: Lisa Hasson

Dead Man Walking

Sister Helen Prejean: Elise Quagliata; Joseph de Rocher: David Adam Moore; Mrs. Patrick de Rocher: Margaret Lattimore; Sister Rose: Karen Slack; George Benton: Kyle Albertson; Father Greenville: Stephen Sanders; Kitty Hart: Kimberly Roberts; Owen Hart: Wayne Tigges; Jade Boucher: Mary Creswell; Howard Boucher: Edwin Griffith; Motorcycle Cop: Kenneth Stavert; Older Brother: Benjamin Schaefer; Younger Brother: Lucas Knoll; Sister Catherine: Nataly Wickham; Sister Lilliane: Stephanie Schoenhofer; Prison Guard 1: Casey Yeargain; Prison Guard 2: Zachary Ballard; Teenage Girl: Madison Densmore; Teenage Boy: Brad Jahner; Anthony de Rocher: Brendan Dunphy; Jimmy: Pierce Mansfield; Conductor: David Neely; Director: Kristine Mcintyre; Set Design: R. Keith Brumley; Lighting Design: Barry Steele; Costumes and Sound provided by Fort Worth Opera; Make Up and Hair Design: Joanne Weaver (for Elsen and Associates, Inc.); Chorus Master: Lisa Hasson

La Traviata

Violetta Valery: Caitlyn Lynch; Flora Bervoix: Ashley Dixon; Annina: Rebecca Krynksi; Alfredo Germont: Diego Silva; Giorgio Germont: Todd Thomas; Gastone: Brenton Ryan; Baron Duphol: Luis Orozco; Marchese D’Obigny: Nickoli Strommer; Doctor Grenvil: Tony Dillon; Flora’s Sevant: Brad Barron; Giuseppe: Joshua Wheeker; Conductor: David Neely; Director: Lillian Groag; Choreographer: Kyle Lang; Set Design: Robert Little; Lighting Design: Barry Steele; Make Up and Hair Design: Joanne Weaver (for Elsen and Associates, Inc.); Costumes from A.T. Jones and Jones, Inc., Baltimore; Chorus Master: Lisa Hasson

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Ory_Sohre2.png

product=yes

product_title=Count Ory in Des Moines

product_by=A review by James Sohre

product_id=Above: Taylor Stayton as Ory and the “nuns” [All photos courtesy of Des Moines Metro Opera]