David Pountney’s production, which uses a new critical edition based on the

1869 version but which reverts to parts of the original 1862 score in Act

3, is the first of three Verdi operas which will be conducted by Carlo

Rizzi over the next three years, with Un ballo in maschera andLes vepres siciliennes following in 2019 and 2020 respectively.

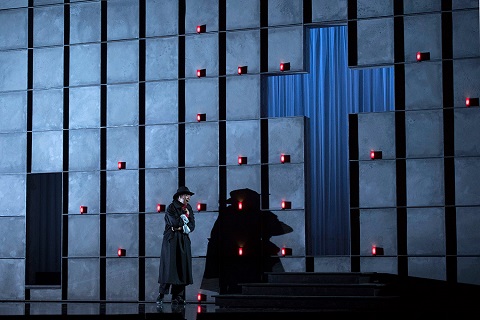

Pountney wastes no time confirming that Fate is exerting its inexorable

grip on the protagonists. Projected onto the plain, angled walls of

designer Raimund Bauer’s set, a wheel spins, slowly gaining momentum,

metamorphosing into a pistol which releases a bullet which surges forward,

unstoppably, towards its target. And, blood will beget blood. The opera’s

first death, of the Marchese di Calatrava, is marked by a blood-splattered

wall which continually weeps red tears in which both of his offspring,

Leonora and Carlo, smear their hands. Religion will offer no consolation:

the monks who watch the disguised Leonora make her ritual progress into the

seclusion of the holy cave in the mountain side, later don blood-stained

mitres.

Verdi, well-known for his adulation of Shakespeare, seems to have tried to

embrace ‘all of life’ – its variety, contrasts, contradictions, epic events

and insignificancies – in this opera. Spanning ten or more years, the drama

ignores the unities of time and action, as his librettist Piave noted in

the opera’s production book: ‘About 18 months pass between the first and

second acts; several years between the second and the third; more than five

years between the third and the fourth.’ (quoted in Julian Budden, The Operas of Verdi, vol.2, (Cassell, 1978)). The opera’s

geography is no less expansive, as the drama travels from an aristocratic

dwelling in Seville, to an inn and hillside monastery near Hornachuelos,

and on to Italy, to a wood and military encampment near Velletri, and back

again to Spain.

And during these years and travels, much happens, as epitomised by a letter

from Verdi to Cammarano, in which he envisages a military camp which later

made its way into La forza: ‘There is a grand scene in this style

in Schiller’s Wallenstein [Wallensteins Lager]: soldiers, camp

followers, gypsies, fortune-tellers, even a monk who preaches in the

world’s most deliciously comic style. You cannot put in a monk, but you can

put in all the rest, and you even can make a little dance for the gypsies.

In short, make me a characteristic scene that will give a true picture of a

military camp.’ (quoted in Franco Abbiati, Giuseppe Verdi, vol.2

(Ricordi, 1959)).

It is surely no accident that the two words which Pountney projects to

preface the two parts of his production, ‘Peace’ and ‘War’, evoke Tolstoy’s

epic historic chronicle. But, Pountney to some extent mimics Fate, in that

he exerts a firm grip on Verdi’s rambling and unwieldy, but potent, account

of Leonora’s elopement with the immigrant Alvaro, a dispossessed Inca

prince, following the accidental death of her father, and the subsequent

vengeful pursuit of her brother Carlo, who refuses to believe in the

lovers’ innocence and for whom only their deaths will suffice as familial

restitution.

Justina Gringyt? (Preziosilla). Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

Justina Gringyt? (Preziosilla). Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

There are, inevitably, some gaps and non-sequiturs that cannot quite be

made to cohere, such as the disconcerting suddenness of the lyrical

outpouring of reunited love in the final act – when Alvaro is recognised by

the presumed-dead Leonora when the latter emerges from a hermitage, after

the lovers have been kept apart for ten years, two acts, and two hours of

music. But, Pountney and Bauer both simplify and unify, to good effect,

making Preziosilla – the young gypsy whose rousing song in Act 2 spurs the

young Spaniards to do battle against the Germans and who predicts for

Carlo, who is disguised as a student, a tragic end – an embodiment of Fate

itself. This black figure – who at times resembles the Queen of the Night,

and elsewhere a cabaret singer from Weimar – prowls through each act,

having initiated the fateful trajectory of the drama with three violent

bangs of her staff in unison with the blaring three chords for brass, horn

and bassoon which open the opera. Justina Gringyt?’s powerful, supple mezzo

really makes its presence felt, infusing the drama with a vibrant energy,

and Gringyt? doubles effectively as Leonora’s maid, Curra, who in this

production is particularly keen to hasten Leonora’s elopement in the

opening scene.

Mary Elizabeth Williams (Leonora). Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

Mary Elizabeth Williams (Leonora). Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

Moreover, the WNO cast live up to Verdi’s hope – expressed in a letter to

his friend Vincenzo Luccardi in February 1863 – that ‘Certainly, in La forza del destino the artists need not know how to sing

coloratura, but they must have some soul and understand the words and

express them.’ (see Franz Werfel and Paul Stefan (eds), Verdi: The Man in His Letters (Vienna House, Inc., 1973)). And,

none more so than Mary Elizabeth Williams, whose soft-edged gracefulness

and ability to withdraw her gentle soprano to the merest pianissimo

conveyed all of Leonora’s dignity, sincerity and sorrow. The intonation

took a little while to settle, and at her quietest she was not always able

to sustain the lyricism of the line, but the emotional impact of Williams’

singing was considerable, and she acted with nuance and conviction. ‘Madre,

pietosa Vergine’, in which the kneeling Leonora begs for divine forgiveness

from the Father Superior whose protection she seeks, was charged with

urgency and redolent with both religious belief and anguished guilt; her

final plea for peace, ‘Pace, pace’, rose persuasively to the top in sublime

intensity.

Gwyn Hughes Jones (Don Alvaro) and Luis Cansino (Don Carlo). Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

Gwyn Hughes Jones (Don Alvaro) and Luis Cansino (Don Carlo). Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

I thought that Pountney might have made more of Don Alvaro’s status as an

outsider, and ‘other’, but Gwyn Hughes Jones used his ringing tenor to

establish Alvaro’s bravado and courage; his sweeping arrival via Leonora’s

balcony was equal in panache to Otello’s ‘Exultate!’, while his third-act

aria, ‘La vita e inferno’, demonstrated expressive nuance. Luis Cansino’s

baritone was full of dark resentment, but his Carlo was rather stiff

dramatically.

I was impressed by MiklÛs SebestyÈn’s Padre Guardiano: the considerable

texture of his bass-baritone brought the character to life, establishing

the Father Superior’s gravitas and empathy, while as the unsympathetic

patriarch, Il Marchese, he was fittingly implacable and resonant.

Donald Maxwell was less full-voiced as the disdainful Friar Mellitone but

conveyed all of the latter’s irascibility.

The WNO chorus were in fine voice, impersonating foolhardy fascists, an

impoverished populace and merciless monks with equal fervour. Carlo Rizzi

demonstrated his innate appreciation of Verdi’s rhythmic arguments – the

tense syncopations of the overture undeniably signalling trouble ahead –

and balanced tempest and tenderness with discernment.

WNO’s spring tour continues:

https://www.wno.org.uk/season/rabble-rousers

Claire Seymour

Verdi: La forza del destino

Leonora – Mary Elizabeth Williams, Don Alvaro – Gwyn Hughes Jones,

Preziosilla/Curra – Justina Gringyt?, Don Carlo Di Vargas – Luis Cansino,

Il Marchese di Calatrava/Padre – Guardiano MiklÛs SebestyÈn, Fra Melitone –

Donald Maxwell, Mastro Trabuco – Alun Rhys-Jenkins, Alcade Wyn Pencarreg;

Director – David Pountney, Conductor – Carlo Rizzi, Set Designer – Raimund

Bauer, Costume Designer – Marie-Jeanne Lecca, Lighting Designer – Fabrice

Kebour, Choreographer Michael Spenceley.

Welsh National Opera, Birmingham Hippodrome; Tuesday 6th March

2018.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/WNO%20La%20forza%20Hippodrome.jpg

image_description=La forza del destino, Welsh National Opera at the Birmingham Hippodrome

product=yes

product_title=La forza del destino, Welsh National Opera at the Birmingham Hippodrome

product_by=A review by Claire Seymour

product_id=Above: Mary Elizabeth Williams (Leonora)

Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith