The words of Benjamin Britten in his speech, On Receiving the First Aspen Award, on 31st July 1964,

two years after the premiere of the composer’s War Requiem on 30 th May 1962 in Coventry Cathedral, the destruction, rebirth and

consecration of which the work was commissioned to commemorate and

celebrate.

Interestingly, in his Aspen Award speech Britten also reflected upon what

he called the ‘so-called “permanent” value of our occasional music’, noting

that we should not worry too much as, ‘A lot of it cannot make much sense

after its first performance, and it is quite a good thing to please people,

even if only for today’. And, pragmatically Britten observed, ‘One must

face the fact today that the vast majority of musical performances take

place as far away from the original as it is possible to imagine’.

There have, inevitably, been numerous performances of Britten’s War Requiem this year, some in gothic cathedrals, others in

venues of diverse function, form and acoustic.

English National Opera’s Artistic Director Daniel Kramer and Turner

Prize-winning artist Wolfgang Tillmans have now brought the War Requiem into the opera house and placed it upon the theatrical

stage. In so doing, they continue the trend for staging Passions, oratorios

and Requiem masses which has seen Deborah Warner, Peter Sellars, Jonathan

Millar, Calixto Bieito et al attempt to make ‘drama’ from ritual

and liturgy.

Britten’s War Requiem captured the sentiments of a world reeling

with the grief of a century of war. Britten spoke in his Aspen Award speech

of the ‘many times in history the artist has made a conscious effort to

speak with the voice of the people’. His belief that it was the

responsibility of the creative artist to communicate directly to society

was expressed time and again: in his speeches on receiving the Freedom of

the Borough of Aldeburgh and on Receiving Honorary Degree at Hull

University’, both in 1962, for example.

But, the Requiem is many things. It is a public statement of the

composer’s own pacifism, prompting our understanding that war does not

cease when warring nations put down their guns. It is also a homage to

Wilfred Owen, whom Britten described as ‘by far our greatest war poet, and

one of the most original and touching poets of this century’. Britten

scholar Philip Reed has suggested that what Britten admired was the

directness of Owen’s poetry and the fact that it highlighted the ‘ironic

conflict of verbal and musical messages’ when juxtaposed with the Latin

Requiem text.

So, in additional to the verbal and musical messages, do we need visual

images too? What will they add, diminish, change?

Essentially, Kramer’s and Tillmans’ War Requiem is a series of

such visual images, presented with technological slickness and potently lit

by Charles Balfour. None of these images are inappropriate; some, in my

view at least, are somewhat hackneyed; some are striking.

Kramer and Tillmans begin with reference to a visually driven narrative

which was designed to bring about social and cultural change. Two halves of

an open book tower over and straddle the stage in the ‘Requiem aeternam’.

The pages of Ernst Friedrich’s War Against War flick over,

exposing the captions and photographs which the young German – an anarchist

and anti-militarist activist who had been incarcerated during WW1 for his

refusal to fight – intended to unmask nationalistic propaganda and lay bare

the false narratives of militaristic rhetoric. Dis?gured faces – ‘The

Visage of War’ – stare at us, as we stare at them: through such visual

activism Friedrich aimed to challenge politically correct ‘ways of seeing’

and create an experienced, rather than imagined, intimacy between viewer

and viewed.

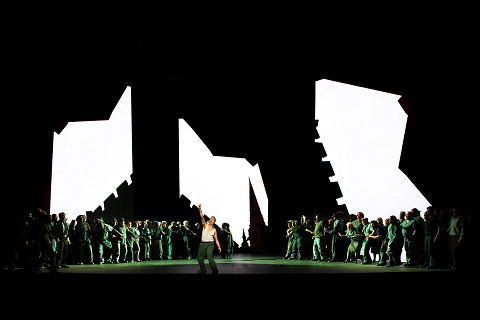

Roderick Williams and Ensemble. Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

Roderick Williams and Ensemble. Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

But, the pages of the book turn quickly, evading our gaze, and are

succeeded by images of other conflicts, horrors and inhumanity. During the

‘Liber scriptus proferetur’, a poster, ‘Breaking the Silence: Gender and

Genocide’, urges us to remember the massacre in Srebenica in 1995. Then,

the uniforms are of a different kind of patriotic allegiance as

bottle-throwing football thugs march through the streets. Monochrome

photographs of the ruined shards of Coventry Cathedral remind us of the

origins of the work – composed in the aftermath of another world war, and

at the height of the Cold War with the threat of nuclear conflict

terrifyingly real – and of Britten’s remark, made during rehearsal for the

1963 Decca recording, that the ‘Libera Me’ “happens today to mean

something”.

Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

Juxtaposed with man’s inhumanity are nature’s cycles of decay, death and

renewal. The camera scrutinises the stripped bark of a fallen tree trunk as

it sheds its protective skin, skims sea-surf scummy with pollution, and

hugs a ground embraced by ferns and moss. A cloud of snow explodes,

bringing another war poem by Owen to mind, with its image of ‘air that

shudders black with snow’. The snow-dust blankets the stage – assuaging and

beneficent, or hostile to man who has negated nature and alienated himself

from its nurture?

There are some moments where image, word and movement are brought together.

‘So Abram rose’ and the ‘Quam olim Abrahae’ are illustrated by an aerial

shot of a sacrificial sheep, as tenor David Butt Philip, dressed in an

officer’s great-coat, oversees a procession children: lambs to the

slaughter, indeed, or as Owen bitterly describes, ‘men who die like

cattle’.

Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

When asked about the ‘sweetness’ of the War Requiem’s final pages,

in an interview with Charles Osbourne in 1963, Britten responded, “I can’t

see any great defect in sweetness as long as it’s not weakness”. At the

close, Kramer and Tillmans open a window on dense, verdant leaves of

renewal, though the lingering agitations of the side drum and snares seem

more in keeping with the ambivalent questions of Owen’s poem ‘The End’:

‘Shall Life renew these bodies? Of a truth/All death will He annul, all

tears assuage?’

The choreography of the enlarged ranks of the ENO Chorus – who sang with

fervency and impact – offers no surprises. They lie motionless, are

marshalled in ranks, they march, they mourn. They, and the projected

images, don’t ‘show’ us anything that we can’t already hear.

Fluctuating grey-green fogginess backlights the ‘Libera me’, but we can

hear the cacophonous slaughter in the violence of the percussion and,

later, in the quasi-hysterical eruptions of the ‘Dies irae’. Moreover, the

power of the customary spatial separation of the three ‘strata’ of the War Requiem – with the two soldiers exposed in the foreground, the

liturgical consolations of the soprano and full chorus behind them, and the

innocence of the children’s choir placed at an unreachable remove – is

lost; as is the contrast between the chamber orchestra and full symphony,

though the ENO Orchestra gave us clanging colours and vivid textures, and

conductor Martyn Brabbins successfully balanced spaciousness and intensity.

Roderick Williams and Ensemble. Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

Roderick Williams and Ensemble. Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

The members of Finchley Children’s Music Group were well-regimented

choreographically and vocally spick and span. Emma Bell’s vivid but

sometimes overly feverish rendition of the soprano solos offered few of the

consolations that we might expect of a celebrant of the Mass. But, tenor

David Butt Philip and baritone Roderick Williams both gave committed and

musically affecting performances.

Roderick Williams and David Butt Philip. Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

Roderick Williams and David Butt Philip. Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith.

The most powerful moments are those of stillness and simplicity. After some

uncomfortable music-hall style gestures in ‘Out there, we’ve walked quite

friendly up to Death’, which weakened the irony inherent in the music, Butt

Philip and Williams stood motionless in ‘Strange Meeting’, freed from the

horrors of the battlefields they have left behind but trapped, restless, in

a mysterious nightmare. The strength of Butt Philip’s tone betrayed all of

the dead soldier’s bewilderment and disillusion, while Williams’ gentleness

accommodated both the bitterness and pity of the counterpart who rises from

the piles of languishing souls and whose ‘dead smile’ expresses his wry

recognition of the futility of war: ‘I am the enemy you killed, my

friend.[…]/ Yesterday through me as you jabbed and killed./ I parried; but

my hands were loath and cold./ Let us sleep now …’.

Here, surely, was the place for Friedrich’s mutilated men for whom there

are no ‘friends/enemies’ or ‘us/them’, only victim-soldiers, and whose

shattered bodies and faces short-circuit conventional oppositional

narratives of conflict?

Kramer and Tillmans demonstrate care and respect for Britten’s work, but

the result feels oddly passive and distanced. And, they risk, in their

emphasis on the visual at the expense of the verbal and musical, turning

the War Requiem into a film score.

Claire Seymour

Britten: War Requiem

Emma Bell (soprano), David Butt Philip (tenor), Roderick Williams

(baritone); Daniel Kramer (director), Martyn Brabbins (conductor), Wolfgang

Tillmans (designer), Nasir Mazhar (costume designer), Justin Nardella

(associate designer, Charles Balfour (lighting designer), Ann Yee

(choreographer), ENO Orchestra and Chorus, Finchley Children’s Music Group,

Sylvia Young Theatre School.

English National Opera, Coliseum, London; Friday 16th November

2018.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Friedrich.jpg

image_description=

product=yes

product_title=Britten’s War Requiem, English National Opera

product_by=A review by Claire Seymour

product_id=Above: Ensemble, War Requiem

Photo credit: Richard Hubert Smith