2020 marked the 20th anniversary of The Sixteen’s annual Choral Pilgrimage tour. In 2000, founder and director Harry Christophers instituted the Choral Pilgrimage, taking the ensemble to English cathedrals from York to Canterbury to present music from the pre-Reformation, as The Sixteen’s contribution to the millennium celebrations. Since then, the Choral Pilgrimage has become central to The Sixteen’s annual artistic programme.

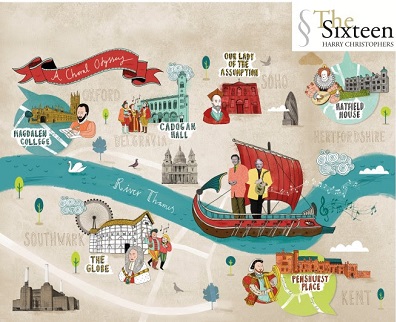

2020 was intended to be the year that the Choral Pilgrimage led to Rome, so to speak – a city which has inspired countless pilgrimages, and where each of the four composers in the year’s programme created some of their finest work. Instead, it became the year a Covid-19 pandemic halted the ‘pilgrims’ in their tracks. But, if you can’t go on a pilgrimage, then perhaps you can experience an odyssey: a long wandering – one filled with adventures, hardships and discoveries. So, The Sixteen’s A Choral Odyssey was born: a five-part series, presented by Sir Simon Russell Beale, exploring choral music and the history behind it, travelling from Our Lady of the Assumption to Hatfield House; from Penshurst Place to the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse at Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre; and culminating in an ‘as live’ relay at Cadogan Hall, weaving together six centuries of festive choral masterpieces.

The Sixteen’s first stopping-place was Magdalen College, Oxford, where they presented a programme exploring the music of two of the finest musicians to have made the College their home: Richard Davy (born c.1465) whose name first appears on the list of Magdalen scholars in the early 1480s when he was still in his teens, and who was organist and Informator choristarum at the College by 1491; and John Sheppard, who arrived at Magdalen as Informator choristarum at Michaelmas 1541 and remained there intermittently until March 1548.

Simon Russell Beale was a genial and curiosity-fuelled host-presenter, engaging in illuminating conversation with Christophers, which established the context, musical and historical, of the music were we to hear. Russell Beale’s gentle prompts elicited helpful information but also enabled Christophers, a Magdalen alumni himself, to unassumingly confirm his admiration for and devotion to this pre-Reformation repertoire and the manuscript sources in which it is preserved.

Richard Davy is perhaps one of the most important composers represented in the Eton Choirbook, the source which presents his setting of a Latin prose-poem – a prayer for grace – ‘O Domine caeli terraeque’ (O Lord, creator of heaven and earth), and describes it as having been composed in just a single day. Before its complete performance, Christophers and his singers, eight on this occasion, illustrated various features of the score – its complex rhythms and imitative textures, the florid musical apostrophe with which the antiphon commences, its use of plainsong. Then, Russell Beale joined Mark Williams, the current Informator choristarum – Organist and Tutorial Fellow in Music at Magdalen – in the College’s Library, to wonder at the glories of a facsimile of the Eton Choirbook’s presentation of Davy’s music. Later, Dr Lucy Gwynn, the College Librarian, studied with Russell Beale an entry in a College register referring to John Sheppard’s involvement with the College: specifically his less salubrious impressment of a young poor boy, sought out for his fine singing and then kept hostage in the College – an act which might have brought the College into disrepute.

The Sixteen’s performance of Davy’s wonderful music was characteristically both soothing and stirring in sonority and texture, melody and decorative gesture: fifteen minutes of glorious counterpoint, changing vocal colours and textures, all seemingly designed to celebrate the spiritual glories that the work, in its ambition and magnificence, itself embodies. Christophers guided his singers effortlessly through the musical riches. In contrast, Davy’s short part-song, ‘Joan is sick and ill at ease’, found three of the singers in the Library, re-enacting a lover’s intercession for the ailing Joan, addressed to St Denis, the first bishop of Paris and patron saint of headaches! Tenor Mark Dobell remarked that this music is not ‘so complex’ but one might describe it as sophisticated simplicity.

Most of John Sheppard’s Latin sacred music was composed for Mary Tudor’s Chapel Royal, but his two ‘Libera nos’ settings for seven-voice choir were written at Magdalen for performance during Compline. The fairly sparse forces here were a perfect medium through which to convey the nuanced imitations and dissonances of Sheppard’s score, and the elongated lines were a comforting musical embrace. Christophers remembered Magdalen scholar and musician, David Wulstan, whose work in restoring the music of the lost tenor-part book brought Sheppard’s music back to listeners’ awareness after centuries of languishing in silence. He recollected Wulstan’s words, “If Sheppard had written nothing else his ‘Libera nos’ would have remained objects of wonderment’. Following the mellifluous expanses sculpted by Christophers and The Sixteen, few would contradict these sentiments.

The next stop on the Odyssey was the Roman Catholic Church of Our Lady of the Assumption and St Gregory in Soho, or Warwick Street Church for short, for a programme entitled International Relations, presenting the music of the Spanish composer, Francisco Guerrero (1528-99). This was a happy coincidence of music and place. As Andrew Stewart’s informative programme article explains, Warwick Street Church began life in the 1730s as a chapel in the garden of the Portuguese Embassy and was one of the few places where Roman Catholics were able to worship freely in London. Fifty years later, Parliament’s efforts to ease anti-Catholic discrimination led to the Gordon Riots during which the chapel was severely damaged. It was re-built in the late 1780s, re-opening in 1790 on the feast of St Gregory and is thus the perfect home for the music of Guerrero, who spent most of his life in his native Seville and whose Catholic devotion led to him being known in his lifetime as ‘El cantor de Maria’.

Above the portal to the sacristy of Warwick Street Church there is a bas-relief depicting the Assumption by the Irish artist John Edward Carew which was originally erected above the high altar. Thus, Guerrero’s motet, ‘Maria Magdalene’, which described the visit of the two Marys to the sepulchre and their discovery of Jesus’s resurrection, was an apt opening. The six parts, enriched by Guerrero’s employed of two bass voices, swelled soothingly and warmly above the high altar, the acoustic aiding the intensity of the sound but never obscuring the part-writing. One could almost smell the scent of the spices (“emerunt aromata”) that the women carry with which to anoint the crucified Jesus, and feel the growing heat of the rising sun (“A orto iam sole”). Discussing Guerrero’s most popular motet, ‘Ave virgo sanctissima’, which probably bestowed the composer’s nickname upon him, Christophers noted both the sensuousness of the imagery and the sounds of the Marian texts so beloved by Guerrero, and the intensity of the composer’s response to them. And this motet did indeed shine with such glorious salutations as “maris stella clarissima” (bright star of the sea) and “margarita pretiosa” (precious pearl), the flowing lines seemingly infinite, the sophistication of the imitation – the two sopranos sustain a unison canon throughout – never obscuring the sincerity of the expressed devotion.

Guerrero wrote 23 hymns which alternate plainsong and polyphony, in what is known as the more Hispano, the plainchant being presented in mensural notation. The men of The Sixteen demonstrated the lively rhythmic lilt of Guerrero’s ttriple-time presentation of the medieval hymn ‘Lauda mater ecclesia’, capturing the dance-like spirit which was complemented by the exuberant imitative treatment of the full ensemble. Did it feel like a dance when one was singing, Russell Beale asked? Simon Berridge’s affirmative reply, “a sort of dad dance”, prompted warm guffaws. ‘Lauda mater ecclesia’ is a hymn for Vespers on the Feast of St Mary Magdalen and Christophers speculated whether it had been sung on the saint’s day, 22nd July, in 1554, two days after King Philip of Spain landed at Southampton, accompanied by his ensemble of singers, the Capilla Flamenca, for festivities designed to culminate in the marriage of the Catholic English Queen and her Spanish counterpart.

Guerrero’s Missa de la Batalla escoutez, is a parody mass, and just one of three of the eighteen masses which Guerrero wrote for Seville Cathedral that are based on secular tunes – in this case the French chanson, ‘La guerre’, composed in 1528 by Clément Janequin to celebrate the victory of Francis I over Swiss mercenary forces at the Battle of Marignano in 1515. Viewers will undoubtedly find Christophers’ illustrated explanations of the devices that Guerrero employs, both in incorporating and developing thematic motifs from the chanson and in responding to the text, informative and engaging. Christophers adopted quite a spacious tempo for the Sixteen’s performance of the Credo from the ‘battle mass’ which allowed the music to breathe and gave it an air of majesty. He broadened the music further for the central homophonic pronouncement, “Et incarnatus est de Spiritu Sancto ex Maria virgine, et homo factus est.”, the singers tenderly presenting this central Christian tenet, before vigour was renewed in the concluding polyphonic statements of faith.

And so, from Counter-Reformation Spain to Purcellian London: On the Town saw The Sixteen cross the Thames to the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse, to ‘take stock of an age marked by political strife and division, deadly disease and civil unrest, and the establishment of civil rights and parliamentary sovereignty’ through a programme of Purcell’s music for the theatre, the ale house and the royal court. Sung from the gallery of the replica seventeenth-century indoor theatre, which stands alongside Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre, an excerpt from the alto duet ‘Let Caesar and Urania live’ from the Welcome Ode, Sound the trumpet, beat the drum (written in 1687 to celebrate the birthday of James II), got the broadcast off to a lively start, Joseph Crouch’s animated two-bar ground bass blossoming into wholesome four-part string textures. Daniel Collins’ and Jeremy Budd’s duet was a lively curtain-raiser for tenor Mark Dobell’s characterful rendition – in the candle-lit theatre, accompanied by cellist Joseph Crouch and David Miller’s theorbo – of the playhouse song ‘Now the fight’s done’ from Nathaniel Lee’s Theodosius. This play was first performed at the Dorset Garden Theatre in 1680 and included nine songs by Purcell, his first for the London stage. Dobell relished the double entendres of the rather risqué text which depicts the gods of love and war as divine beings with very earthly passions. Purcell’s music danced insouciantly.

This song must have been popular in its day, for there are nearly thirty broadside ballad arrangements, the texts often extended and politicised by the balladeer-poets. For example, Nathaniel Thompson’s Choice Collection of 180 Loyal Songs (published in 1685 and 1694) re-prints Purcell’s tune with three different ballad texts relating to the Popish Plot of the late 1670s: one celebrating its discovery; another relating the hanging of Stephen College, ‘The Protestant Joyner’ executed on rather dubious evidence for his seditious involvement; and a third, ‘The Compleat Swearing Master’, which attacks Titus Oates, the English priest who invented the fictious conspiracy. Catches – essentially rounds for three or four unaccompanied voices – similarly often engaged with political events, though since they were largely intended for the tavern they took as their main themes wine, women and national pride. So, fittingly, the gentlemen of The Sixteen gathered in the bar of the Swan Restaurant at the Globe and invited Simon Russell Beale to join them in one such catch melody. True Englishmen drink a good a health celebrates the acquittal in 1688 of seven Anglican bishops who had refused to read to their Protestant congregations James II’s 1687 Declaration of Indulgence granting Catholics new rights, and were jailed for their convictions. After a hearty sing-through, the high range of the catch – typically so, commented Christophers – prompted Russell Beale to remark the singers would presumably have benefited from a drink or two to loosen their vocal cords for such raucously joyfulness of couplets as “Then remember the sev’n who supported our cause,/ As stout as our martyrs, and as just as our laws.”

Back in the Theatre, Christophers guided Russell Beale through the many riches of Sound the Trumpet, explaining – with illustrative support from his singers and musicians – how Purcell uses the voices to mimic martial instruments at the opening of the Ode, creating a majesty to match the effusive allegorical imagery. He discussed the inventiveness of the composer’s ground bass variants; and, the way that the agility and range of the renowned bass John Gostling, a singer from Canterbury whom Purcell brought to London to sing in the Chapel Royal, inspired the virtuosity of the aria ‘While Caesar, like the morning star’. Purcell’s endless varieties of texture and colour were highlighted too, the “infectious fun” of the instrumental Chaconne contrasting with vocal trios and sextets, the latter enriched by wonderful word-painting.

This was an engaging and enlightening introduction to a complete performance of the Welcome Ode. The crisp rhythms and tight ornaments of the opening Symphony movement slipped fluently into a triple time dance, and on again into the dignified pronouncement, “Sound the trumpet, beat the drum,/ Caesar and Urania come”, sung with gravity and colour by high tenor Jeremy Budd and bass Ben Davies. “To Caesar all hail, unequall’d in arms!” mirrored the Chorus, the warm mellifluousness and fine ensemble of the singing almost making the sycophantic flattery sound sincere! It was a joy to hear the alto duet once again, especially the complete instrumental response, which was played with lovely dynamic nuance. The richness of the choral textures complemented the refinement of Chaconne, the latter alternating vigour and delicacy, with the minor tinges towards the close adding a hint of melancholy that was, just, kept at bay by the sustained momentum. In his solo aria, bass Stuart Young plummeted down to a low D and then easily reached the vocal peak, more than two octaves higher, and negotiated the extended decorative runs effortlessly – Gostling might have met his match! I loved the way the instruments interjected small motivic echoes, heightening the vocal rhetoric. After the rousing majesty of the concluding Chorus, “To Urania and Caesar delights without measure,/ With empire no trouble, and safety with pleasure”, it was no wonder that Christophers was smiling.

Hatfield House, home for a time to the young Elizabeth I, played host to The Sixteen for their programme of music by William Byrd and Arvo Pärt, its title, A Matter of Conscience, reflecting the fact that both composers faced attempts by their respective states to supress their religious convictions, Byrd’s Roman Catholicism setting him at odds with the law under Elizabeth I and James I and Pärt’s musical expression of his Orthodox Christianity bringing him into conflict with the Soviet authorities. The House, a Jacobean manor set in a large Great Park in Hertfordshire, was built in 1611 by the first Earl of Salisbury and son of William Lord Burghley, Robert Cecil, who was Chief Minister to both Elizabeth I and her successor, James I. As well as being the most powerful man in England, Cecil was also a generous patron of the arts, particularly architecture and music, and the Hatfield House archive attests to the many Tudor and Elizabethan musicians who benefitted from his munificence: Nicolas Lanier, the first Master of the King’s Music, is known to have been in Cecil’s employ, while Thomas Morley, William Byrd and John Dowland were among those who dedicated pieces to him.

In 1575 William Byrd and Thomas Tallis were granted a 21-year monopoly over the printing of polyphonic vocal music in England, and their first publication under this arrangement was a collection of Latin motets, the Cantiones Sacrae, each composer contributing seventeen items, to celebrate Elizabeth’s seventeen years as Queen. One of the longest works, Byrd’s Tribue Domine was originally listed as three separate items in the index, but in 1975 analysis by Joseph Kerman showed that they formed part of a single twelve-minute motet. Kerman described it as ‘the most ambitious composition written by William Byrd in his early years’.

Christophers and Russell Beale began by discussing the unusual text that Byrd chose to set. Neither biblical nor liturgical, it has no evident liturgical context, and was in fact drawn from an anonymous medieval book, Meditationes, that was said to be written by St Augustine of Hippo, although even in Byrd’s day there was scepticism about the authorship. It was a popular text during the latter part of the 16th century, in England and Europe. Robert Cecil’s father owned a copy, one that was printed 1529 by a member of the distinguished Froben family, and is now in the Library of Hatfield House. Russell Beale and the current Marquess of Salisbury studied Burghley’s signature in the book, in Latin, seeking out the text that Byrd set. Christophers noted that it is also thought that Elizabeth knew and admired the Meditationes. Indeed, there is there is a copy of the English New Testament in the Bodleian Library which contains a handwritten excerpt from Chapter 22 of the Meditationes in Thomas Rogers’s 1581 English translation, with a marginal note in another hand that observes: ‘This was queene Elizabethes booke & this was her owne hande writting above’, but the authenticity of the inscription is not certain.

Turning to the music itself, Christophers considered, and his singers illustrated, the relationship between musical and architectural space and form, Byrd’s use of vocal entries and textures to reinforce the meaning of the text, and his expressive use of false relations. ‘Tribue Domine’ seems rather backward looking with its alternating and contrasting vocal groupings, but as always Christophers’ sure sense of pace and proportion made the first part of the motet feel fresh, and the organic development of the music was smooth and persuasive. Part 2 was more dramatic, tenor Jeremy Budd’s entry with the text “ut per fidem rectam” (that through that upright faith and the good works of faith we may, with your mercy, win eternal life), ‘completing’ the six-part texture and affirming the ‘rightness’ of that faith – as Christophers reminded us, the Catholic faith. The striking declamation was followed with lines of greater floridity and freedom, the imitation denser, the chromatic nuances more frequent, culminating on a joyful tierce de Picardie. Sparser textures characterised Part 3 praises, “Gloria Patri, qui creavit nos” (Glory be to the Father who made us) but after the airiness and lift, the six voices proclaimed majestically, “gloria summae et individuae Trinitati, cuius opera inseparabilia sunt,” (glory to the most high and undivided Trinity) the false relations seeming to meld the vocal lines together inextricably. Lighter rhythms articulated the joyfulness of “Te decet laus, te decet hymnus” (to you belong hymns of praise) the voices arriving on the final syllable of “A-men” at different times, as if the music itself was reluctant to come to an end. It’s hard to think of anyone who has a more compelling feeling for the architecture and ambience of this repertoire than Christophers.

Four centuries separate Byrd and Arvo Pärt but as Christophers reminded us, both suffered political and religious persecution and their music is the expression of belief. I sometimes find Pärt’s gestures and harmonies too predictable, but Christophers suggested that this is not so; and that, in any case, Pärt’s simplicity and the absence of musical rhetoric for its own sake, may draw us closer to the text. I heard The Sixteen perform The Deer’s Cry in Music for Reflection, a programme which was broadcast live from Kings Place in September – part of VOCES8’s Live from London festival. Pärt sets a 5th-century text thought to be by Ireland’s patron saint, St Patrick, which tells the story of Patrick leading a group of monks through the woods, following an ambush: they are taken for a mother deer and her calves, and so they are saved. Here, the repetitions seemed more fragile, “Christ with me”, “Christ in me”, but the silences between them less halting, and there was a greater sense of building to a sonically thrilling confirmation of faith. The acoustic of the Hall seemed to make the sound ring full and pure – not disembodied, but natural, innocent, lifted by the fervour of the human spirit as it seeks the divine.

After Christophers had discussed the tintinnabuli technique which Pärt developed in the 1970s, we heard the shimmering power of its bell-like glow in the composer’s Nunc Dimittis. But, Christophers did not let the sound become a haze: textures were sculpted, the overall timbre was quite austere, and the vivid harmonic contrasts built with rhythmic power towards an almost ecstatic sense of resolution, sealed in the ringing, swinging Amens.

As Russell Beale concluded, the sacred music of these two composers “transcends the ever-changing weather of politics. Above all, it offers consolation and comfort, a sense that there is hope, no matter how adverse the times.” Byrd’s eight-part motet, Diliges Dominum, from the 1575 Cantiones Sacrae – a musical palindrome – was the perfect response to his summation, and was sung by The Sixteen with unforced nobility: “Deum diliges proximum […] tuum sicut te ipsum.” (You shall love the Lord your […] God you shall love your neighbour as yourself.”

The Journey’s End of this Choral Odyssey was reached at Penshurst Place, home of the Sidney family since 1552 when the house was given to Sir William Sidney by Edward VI, in reward for his service as the boy king’s tutor and steward of Edward’s household. With Christmas approaching, The Sixteen celebrated the carol, old and new – and old carols made new.

Penshurst Place was built two centuries before the arrival of the Sidneys and is home to one of the last standing medieval baronial halls. And, so, it was to the Middle Ages that The Sixteen returned to start their programme, soprano Alexandra Kidgell and lutenist David Miller welcoming us to Penshurst with the anonymous song, ‘Sweet was the Song’ – a song designed to spread the Christmas message and celebrate the humility and compassion of the Virgin Mary. The polyphonic carol ‘Nowell, Nowell in Bethlem’ presented a strikingly vigorous contrast, its ‘burden’ – the line or couplet repeated between each verse and conveying the essential ‘meaning’ of the carol – sung with strength and vitality by the ensemble voices, “Nowell, nowell, nowell!/ To us is born our God, Emmanuel”, punctuating the lighter verses sung by Kidgell and tenor Jeremy Budd. Christophers speculated that, during the 1400s when the house was owned by Henry IV’s music-loving son, John of Lancaster, the first Duke of Bedford, this may have been just the sort of carol that entertained the Christmas guests at Penshurst.

The spirit of the dance is never absent in these medieval carols, which were an essential part of pagan and pre-Christian festivities held at harvest time and to mark the changing of the seasons, as well as a feature of Christmas banquets and processions in medieval times. Such carols are preserved in many manuscripts. ‘Nowell, Nowell in Bethlem’ is found in the so-called ‘Trinity Carol Roll’, a 15th-century manuscript of thirteen English carols held by the Wren Library at Trinity College Cambridge, while a manuscript in the Bodleian Library, dating from the mid-1400s, contains both the ‘Salutation carol’ – “Nowell, Nowell, Nowell! This is the salutation of th’angel Gabriel” and ‘Make we joy now in this fest’. The former presents a unison melody – probably an existing folk song, Christophers surmised – with muscular rhythmic vitality: and so, wrapped up in warm coats and accompanied by tambourines, the men of The Sixteen ventured into the chilly winter air to give a rousing rendition, led by bass soloist Ben Davies. Back inside the medieval hall, ‘Make we joy now in this fest’ whipped up a similar triple-time swagger, with tenor Mark Dobell and bass Tim Jones now delivering the solo verses between the robust ensemble burden.

Christophers remarked the fascination that such medieval carols, and especially their texts, held for many 20th-century composers, such as Benjamin Britten, Richard Rodney Bennett and William Walton, and The Sixteen offered us the opportunity to hear ‘Make we joy now in this fest’ again – in the arrangement made by Walton in response to a commission in 1931 from the Manchester-based newspaper, the Daily Dispatch, and which was published therein on Christmas Eve that year. The ‘spiced up’ harmonies and gentle melismas enriched the narrative, and Christophers shaped the repetitive structure with acuity, carrying the listener through the carol’s story.

One extant Renaissance manuscript, explained Christophers, contains music – twenty songs and some instrumental pieces – composed by Henry VIII, the King’s music appearing alongside works by some of the principal composers of the period, such as Robert Fairfax and William Cornysh. The music-loving Henry had built up a retinue of almost 60 musicians by the end of his reign and Christophers suggested that it was unimaginable that when visiting Penshurst Place, which at the time was a royal hunting lodge, the monarch did not bring his musicians with him to perform songs such as Henry’s own ‘Green Grow’th the Holly’. Only the burden survives – perhaps the verses were a popular song of the day, Christophers wondered – and so The Sixteen commissioned Cecilia McDowall to provide them with new verses. McDowall’s beautiful melody, sung eloquently by Davies, wonderfully matches both the grace and the increasing sophistication of the repeating burden, and Christophers shaped the sopranos’ ‘angelic’ rise at the cadence of the latter exquisitely.

Miller re-joined the men for the anonymous ‘Angelus ad virginem’, a carol which is mentioned in Chaucer’s ‘The Miller’s Tale’, and McDowall once again brought medieval and modern together in the triple-time ‘Now may we singen’, the refrain of which imitates the common macaronic practice of integrating English and Latin texts: “Now may we singen as it is. Quod puer natus est nobis.” This was a terrifically energising performance by The Sixteen: the singers relished the hemiola tugs-and-sways, articulated the verses with precision and lightness, ‘dug in’ to the sonorous bass drones, and made the quite ‘spare’ music utterly infectious. McDowall employs some of the same techniques in ‘Of a Rose’ which concluded this celebration of the carol in exciting fashion, The Sixteen clearly enjoying the vocal demands which McDowall’s carol presents.

That was not the last time The Sixteen would sing McDowall’s music during this Christmas season, however: ‘Now we may singen’ concluded their final festive celebration at Cadogan Hall where, now eighteen-strong, they were joined by Simon Callow for The Truth from Above – a programme which took its theme and title from the opening line of an English folk carol, which the ensemble performed in a version collected by Ralph Vaughan Williams in 1909 and arranged by him in four parts. It opened their programme, recorded as live, with graceful gravity and dignity.

In conversation with Simon Callow, Christophers wryly reflected that a concert by The Sixteen couldn’t fail to include music from the sixteenth century, the ensemble’s ‘bread and butter’. And, so, we heard two settings of the Advent motet ‘Rorate caeli’ (Drop down ye heavens from above), Palestrina’s rich and restrained polyphony contrasting with Byrd’s more freely expansive and energised lines which respond with such vigour to the text. Separating the Renaissance polyphony, however, was Howard Skempton’s beautifully atmospheric ‘Adam lay ybounden’, while Boris Ord’s more well-known setting of the 15th-century text separated ‘Laetentur caeli’ (Let the heavens rejoice) by Byrd and Lassus.

The Sixteen did not sing the carol that Christophers confessed is his favourite, ‘In the Bleak Midwinter’, but they did present several traditional carols, including ‘Gabriel’s Message’, which was sung with flowing directness, the phrases tapered most eloquently, and the Wexford Carol. The purity of the unison plainsong ‘Veni, veni Emannuel’ preceded Jonathan Dove’s ‘I am the day’, which weaves the melody of the plainchant hymn into the upper voices of the choral texture in its second section. The contrasts between intensity of sonority and fleet-footed staccato spriteliness were striking and The Sixteen confirmed the acuity of Dove’s response to text. The ending was blissfully ethereal. There was a quasi-medieval simplicity, too, in the quiet drone and tuneful melody of Will Todd’s Rutter-esque ‘My Lord has come’, though the jazzy harmonies added a sense of wonder to the gentleness. In contrast, in ‘Carol of the Bells’, Philip Wilhousky’s English-language version of Mykola Dmytovich Leontovich’s arrangement of the traditional Ukrainian new year song, ‘Shchedryk’, and the closing carol, ‘Ding, dong, merrily on high’, The Sixteen offered buoyant Christmas blessings.

As Simon Callow reflected, both the traditional carols and more modern ‘art-songs’ and carols tell the same story – that of Christ’s nativity. This programme offered actual ‘stories’ too, in the form of Callow’s own narrations of Nicholas Allan’s Jesus’ Christmas Party and Clement Clarke Moore’s A Visit from St Nicholas.

The way composers tell us stories was something to which Simon Russell Beale and Christophers had returned throughout the Choral Odyssey. During their journey, The Sixteen and Harry Christophers proved themselves similarly accomplished, compelling and companionable musical raconteurs.

All episodes of The Sixteen’s A Choral Odyssey are available to watch on demand until 31st March 2021.

Claire Seymour

A Choral Odyssey was broadcast on five Wednesdays between 18th November and 16th December, with the Christmas Concert from Cadogan Hall streamed on 23rd December. The performers during A Choral Odyssey were:

Harry Christophers (director)

Julie Cooper, Kirsty Hopkins, Katy Hill, Alexandra Kidgell, Charlotte Mobbs, Emilia Morton (soprano)

Daniel Collins, Edward McMullin, Kim Porter, Hugh Cutting, Elizabeth Paul, Simon Ponsford (alto)

Jeremy Budd, Mark Dobell, Simon Berridge, George Pooley, Tom Robson, Nicholas Mulroy (tenor)

Ben Davies, Rob MacDonald, Tim Jones, Stuart Young, Eamonn Dougan (bass)

Sarah Sexton, Daniel Edgar (violins), Martin Kelly (viola), Joseph Crouch (cello), David Miller (theorbo, lute), Keith McGowan (harpsichord), Charlotte Mobbs, Robin Barda (tambourine)