I raved about Greek-born baritone Tassis Christoyannis’s CD of songs by Félicien David and a follow-up 2-CD set of songs by Édouard Lalo . In American Record Guide, the late Charles H. Parsons praised the “style and eloquence” of his singing in Gounod’s opera Cinq-Mars (March/April 2017). And Robert A. Moore, reviewing a CD of songs by Saint-Saëns with orchestral accompaniment (in which he was joined by the superb tenor Yann Beuron), said his “intoxicating” singing has “a Gallic tone” (likewise in ARG: July/August 2017). Anne Ozorio was just as enthusiastic about that disc of songs-with-orchestra here at OperaToday .

Robert Moore praised, as well, Christoyannis’s performances—with pianist Jeff Cohen—of a selection of “imaginative and delightful” songs by Benjamin Godard (ARG, July/August 2016) and admired his “artistry”—and Cohen’s—in the “thoroughly enchanting songs” of a forgotten figure: Fernand de La Tombelle (ARG, September/October 2017). In short, this Greek-born artist has become a major proponent of the uniquely French (one might think) art of putting French vocal music across.

Here Christoyannis and Cohen provide a CD of Saint-Saëns’s four song cycles for solo voice and piano. Like all of the aforementioned, it was made possible through the financial and scholarly support of the increasingly indispensable Center for French Romantic Music, located at the Palazzetto Bru Zane (Venice).

The baritone’s singing is as gorgeous and many-faceted as before, ranging from delicate to full-voiced, hitting the pitch squarely, and phrasing with what feels like innate musicality. (Two notes are distinctly sharp in the first song; there should have been a retake.) Some of the poems are written from the point of view of a man; others, a woman. Regardless, Christoyannis leaps convincingly into each song as if creating it anew in front of us. He is powerfully assisted by Cohen, who, though American-born and -trained, is now one of the most renowned collaborative pianists in France.

The four collections are called cycles in the helpful booklet essay, but they are not cycles in the strictest sense of that word: none of the four tries to tell a story, in the manner of Schumann’sFrauenliebe und -leben or Fauré’s La chanson d’ Ève. (On the Fauré, see my review of a recording by Norwegian mezzo Bettina Smith .) Nonetheless, each cycle (or set or collection) consists of songs that inhabit a single coherent world of feeling, are somewhat consistent in musical manner, and often use images closely related to those in other songs in the cycle.

The best-known of the composer’s four song cycles is Mélodies persanes: six songs describing different aspects of life in a richly imagined Middle East, as conjured up in poems from a collection, with the same title, by a contemporary poet and government functionary, Armand Renaud. As Renaud explained in the preface to his verses, he drew, for inspiration, on various Middle Eastern poems that had recently been translated into French, e.g., by Hafiz, Rumi, and Omar Khayyam. He also tried to avoid using foreign words, in the hope of creating a sense of directness for the French reader that was equivalent to what a Persian, say, might find in a Persian poem.

I would love to write (and perhaps someday will write) pages on the musical features of this cycle: the enchanting mixture of pseudo-Middle Eastern modality (Dorian mode, in “La brise”—”The Breeze”) and functional tonality, the occasional bits of pseudo-Oriental melisma (“Sabre en main”—“With Saber in Hand…”), percussive dance rhythms (“La solitaire,” in which “The Lonely Woman” yearns to be carried off by a dark-eyed man on horseback), and numerous spots in which the meter shifts unpredictably or the phrases vary in length (“Au cimetière”—“In the Cemetery”). There is a wonderful long mock-triumphal piano coda to the fourth song (“Sabre en main”), conveying the fantasy of the protagonist (apparently a young Middle Easterner, or maybe a middle-aged Frenchman wishing he were one!): “I want the world to writhe at my feet / And realize how little it is worth!” Saint-Saëns spent numerous vacations in North Africa and even wrote with some discernment about music that he encountered there. (Indeed, he was sojourning in Algiers when he died.) Still, he would have been the first to admit that his evocations are basically French music, if with an intriguing foreign accent.

The words of the songs amount to a fascinating collection of what we today are likely to consider outdated stereotypes (sensual women, men with swords and daggers, the whirling of a dervish in an opium haze, and so on). I suspect that, in the late nineteenth century, such images may have been all too readily taken as more or less accurate reportage and thus may have helped justify France’s colonial control of North Africa. (The imposition of French rule allowed the composer to enjoy those delightful stays in Algeria in, presumably, European-owned and -run hotels.) True, Renaud focuses his attention explicitly on Persia. But many of the images in his poems would clearly have been understood as relating to other lands in the Middle East of his day, that is: the vast regions in which people spoke Arabic, Turkish, or Persian.

The composer also orchestrated this cycle, expanding it to include two new songs and dividing it into four sections, each of which he preceded with a new orchestral prelude. That version of the cycle requires tenor, contralto, and chorus and is entitled La nuit persane.

On the orchestral-songs CD mentioned above, Christoyannis performs two of the Mélodies persanes in the composer’s own lovely orchestrations. One, “La brise,” is a song that is taken by chorus in the expanded cycle, La nuit persane, but Christoyannis sings it alone; the other, “La splendeur vide” (“Empty Splendor,” a rueful meditation on life without love) is the one song from the original cycle that the composer ended up excluding from La nuit persane (apparently only after going to the trouble of orchestrating it).

Two of the cycles on the CD are based on poems from centuries earlier: Cinq poèmes de Ronsard and Vieilles chansons. The poems are full of charm and wit. Ronsard, for example, loved to play with internal rhyme and unusual line-lengths: “Son oeil ardent / Dardant / En moi / L’émoi / Du feu…” (“Her burning eye / Shooting / Into me / The agitation / of fire”). One can see why Saint-Saëns, who was an agile writer himself (prose and also some poetry), was attracted to these vibrant verses. He responded with delightful music, often colored by musical features of earlier eras, though not usually from as far back in time as the poetry. The poem I was just citing, by Ronsard (who lived in the 1500s), gets matched to a piano part that seems indebted to a much-loved piece by Bach: the Little Prelude in D Minor BWV 935 (ca. 1720).

The biggest surprise on the disc is the cycle La cendre rouge, to poems by Saint-Saëns’s contemporary Georges Docquois. The composer seems to have written these songs in a spirit of experiment, as he confided to his publisher (with some wordplay): “My new mélodies are scarcely melodic. They resemble nothing that I have done before nor what others do. I do not know if the songs will please, but I take pleasure in writing them.”

He was exaggerating a bit. I hear one previous composer, in particular, in some of La cendre rouge: Schumann. As in many Schumann songs, the piano part is often almost an independent composition, on top of which the voice declaims the text with a certain naturalism. The first song, in particular, reminds me of “Zwielicht” (from the EichendorffLiederkreis, Op. 39, or “Mein Herz ist schwer” (from Myrthen, Op. 25): all three begin with a tortuous, unharmonized opening line for piano alone. The end of the song, with the words “You will see flying in the breeze / The red ashes of your heart”, may remind many of the final phrases of “Ich grolle nicht” (from Dichterliebe), but with a difference, for the poetic persona in the Saint-Saëns is singing about his own betrayed heart, not the cruel one of a woman who has spurned him.

There are numerous surprising moments in this ten-song cycle. In the second song (“Sad Soul,”, Track 16) I loved the brief evocation, by the piano, of a guitar and then a jester, both ironically mentioned as unable to silence the character’s sobbing. And the fifth song, “Easter,” evokes a wonderful sound-portrait, from the piano, of multiple church-tower bells inviting poor people to don their newest clothes and forget their woes for a day.

Several of the songs explore more advanced chromatic harmonies than was customary for Saint-Saëns, often as response to cues in the text (e.g., anguish or unease). For example, in the fourth song (“Silence”), the two startlingly exploratory piano interludes seem to represent the thoughts of the poem’s loving couple: thoughts that the two are—the words tell us—sharing at most through glances, not words.

Christoyannis’s pronunciation is, as on previous recordings, remarkably good for a non-native. He makes the wise decision to place his r’s at the tip of the tongue, Italian-style (a standard option in sung French), thus avoiding the tricky guttural r. I noticed one wrong word (“de” for “que” in Track 10, in which he otherwise manages the rapid patter astonishingly well) and one unvocalized s (i.e., it should have sounded like a z), also a few impure vowels (“nos” for “nous” and “de” for “des” in Track 18). But these are minor slips. He has clearly thought about the words and their meanings, and he finds a vast palette of matching colorations in his voice: playful or tearful, bragging or pleading. I would love to see Christoyannis onstage in an opera. (He is in some opera DVDs, but I have not seen them: Germont père and Ford, both from Glyndebourne.) He also trills well, despite having a voice that is rich-textured rather than (as with certain early-music specialists) narrow as a pin. One song (“La brise”) can be heard here, others are on YouTube, and the whole CD can be streamed from Spotify and other services.

The CD booklet, with the immensely helpful essays and song texts, all in first-rate translations by Charles Johnston, can also be downloaded from Naxos Music Library .

This now makes yet another gorgeously sung recording that has come my way in a recent years, following up on ones featuring Véronique Gens (Lalo and Coquard’s opera La Jacquerie), Karine Deshayes (Rossini-aria CD), Aida Garifullina (debut aria-recital), Carolyn Sampson , Cyrille Dubois , Pavlo Breslik , and, in perhaps the best-ever recording of Ravel’s L’heure espagnole, Gaëlle Arquez and Mathis Vidal . Are we entering a new Golden Age of Singing?

Ralph P. Locke

Saint-Saëns: Mélodies persanes, Cinq poèmes de Ronsard, Vieilles chansons, La cendre rouge

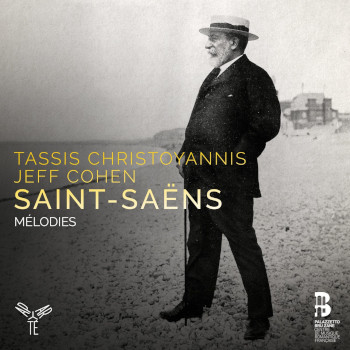

Tassis Christoyannis, baritone; Jeff Cohen, piano

Aparté AP132 – 72 minutes

Above: Tassis Christoyannis [Image courtesy of Operabase]