Rome, the 1620s. Johann Hieronymus (Giovanni Girolamo) Kapsberger, virtuoso theorbist, singer and esteemed composer is at the peak of his fame and influence.

Born to German parents in Venice in c.1580, he has arrived in Rome by 1605. Nicknamed ‘Venetus’ and ‘Italus’ during his school days in Germany, in Rome he is known as ‘Il Tedesco della tiorba’ or ‘Il Tedeschino’. His ‘noble’ heritage has served him well: the most celebrated theorbist of his day, he performs before highly exclusive audiences in aristocratic palazzi and papal courts, and in 1611 is admitted to the Academia degli Umoristi, one of the most elite circles in Rome. Favoured by the wealthy, powerful Barberini family, including Cardinal Francesco Barberini, the nephew of Pope Urban VIII, in 1624 he commends himself to the latter with the dedication of his Poematia et carmina, which set poems written by the Pope himself. Urban VIII duly commissions mass settings in the style of Palestrina which are performed in the Sistine Chapel and invites Kapsberger to play in his private chamber.

But, arrogant, petulant and irritable, Kapsberger makes enemies. The most esteemed vocal group in Rome, the Cappella Sistina, refuse to sing his music: performances are sabotaged, his manuscripts stolen and destroyed. The Queen’s Squadron – that group of ladies-in-waiting recruited by Catherine de Médici to maintain harmonious relations at court, who have equal taste and talent for music and espionage – begin their covert reconnaissance. The ladies – Veronica, Clara, Renata, Josepha and Alba – move among the servants and pickpockets, the lovers and the lunatics of Rome; suspects are found false. Then, in a room they disturb a lady, languishing in the agony of love’s deceptions, tearing to shreds the pages of Kapsberger’s manuscripts – music which he loves more than any woman. The fragments have been hidden under an unknown stone. Can the Queen’s Squadron discover their whereabouts and restore them to their creator? Will Kapsberger’s music survive the conspiracies of the present and earn him the adulation of posterity?

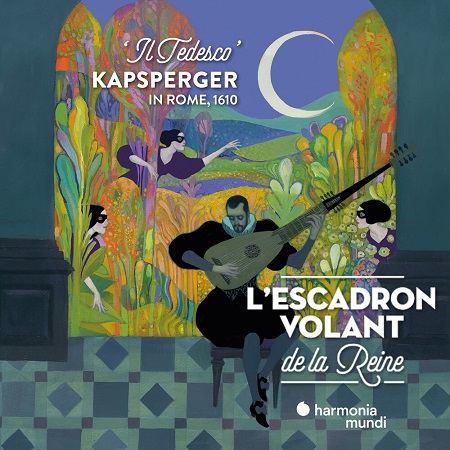

And, so, fact meets fiction. Little is known of the events of Giovanni Girolamo Kapsberger’s life, though rumours abound. In his short narrative, ‘The Kapsberger Affair’, the Belgian writer Carl Norac reaches into the Caravaggio-esque shadows of the composer’s life and art, and illuminates a tale of intrigue and passion, revenge and restitution. Recently appointed Poète National de Belgique (2020-22), Norac is the author of several fictions related to musical subjects, including Le Carnaval des animaux de Saint-Saëns (1999), Monsieur Satie, l’homme qui avait un petit piano dans la tête (2006) and Monsieur Chopin ou Le Voyage de la note bleue (2009). ‘The Kapsberger Affair’ is a somewhat arch literary complement to the selected madrigals, villanellas and airs which form L’Escadron Volant de la Reine’s debut album, Giovanni Girolamo Kapsberger: Il tedesco a Roma, recently released on harmonia mundi.

L’Escadron Volant de la Reine were founded by Antoine Touche in 2012. The ensemble brings together young musicians from European conservatoires who, they profess, are united by their friendship and their affection for Baroque music. Though the subtitle of the album locates Kapsberger in Rome in 1610, the 25 compositions that they present here are in fact drawn from various sources, the earliest being Kapsberger’s first book of madrigals for five voices and continuo, published in Rome in 1609, the last the 1640 Libro quarto d’intavolatura di chitarrone. Though he composed in many genres, secular and sacred, Kapsberger is best known today for his music for theorbo, so it is good to have the vocal-instrumental balance redressed here.

I had imagined that the musical sequence would, however freely, somehow relate to the unfolding literary narrative by Norac, but that’s not the case. The music stands alone. There are homophonic and imitative ensemble madrigals, with frequent episodes in parallel thirds, as well as intense ariosos for solo voice and diverse instrumental combinations. The villanellas are more earthy – strophic, with robust continuo accompaniments, often dance-like with shifting dule and triple meters. The texts, the authors of which are not identified, predominantly reflect on the pains and pleasures of love. Instrumental numbers weave between the poetic plaints.

Few of the vocal numbers are more than a few minutes in length, many considerably shorter, though they each establish a strong identity. The opening items capture the flavour of contrasts and colour. ‘Lunge da voi ben mio’ steadily builds in intensity from third-based exchanges with forthright organ; ‘La mia leggiadra Filli’ is more imitative, the individual voices strongly characterised within the ensemble. Between these two madrigals is placed a ballo from the 1615 Libro primo de balli, gagliarde et correnti, a quattro voci in which the violin and viola da gamba move with light grace, propelled by a flexible theorbo that engages melodically and contrapuntally, harmonically and texturally.

If, described thus, this collection sounds rather conventional, then the performances are anything but. Immediacy, interaction and an improvisatory air are prioritised over perfection and polish – though that’s not to say that there is not considerable virtuosity on display, just that vitality takes precedence. The music pulses with real human feeling, and the singers and musicians of L’Escadron Volant de la Reine relish the poetic and aural piquancies.

On first hearing, there were musical moments – changes of direction, mood or timbre – that really did startle, sending me back to the beginning of a madrigal or sinfonia to better understand the expressive means and effect. ‘Nelle guancie di rose’ begins with voices alone, the textures homophonic, the text purposefully articulated. Then, a harp clatters through a downwards swoop, as the voices despair of bitter love that is nourished on poison – “Deh, come acerbo amore”. Rhythmic and timbral agitation ensue, until the striking contrasts of the close culminate in writhing dissonances: “Il mio morir mirate, E se pietat’avete, il mio morir piangete.” (Behold me as I die, and, if you have any pity, mourn my death.) It’s a lot to pack into one and a half minutes.

In the lovely duet ‘Su l’erbe affissomi’, harp and theorbo provide elaborate undercurrents, voicing the intimations of the simple, strophic vocal lines. The bass solo ‘Sconsolato mio core’ blends mannered, stylish madrigalisms with agile viola da gamba commentary. The music feels genuinely ‘alive’, as Renaud Bres presses urgently through the text, “Non paventar, cor mio, che vedrai pia/ Nel tuo longo soffrir la Donna mia”, seeking to reassure his heart that his lady will have mercy on his long suffering. (Individual singers are not identified in track information so apologies for any misidentifications.) ‘Ultimi miei sospiri’ is drawn from the Libro secondo d’arie passeggiate a una e più voci, con l’intavolatura del chitarone, published in 1623. Its text is more meditative, the solo monody dark and intense, fired with rhetorical fervour: “Dite: ‘O beltà infinita, Dal tuo fedel ne caccia empio martire.’ (Say to her: ‘O infinite beauty, a cruel torment chases us from your faithful lover!’) Countertenor Damien Ferrante’s diminutions and dissonances burn with the text’s repressed emotions.

The vivacity of the ensemble is palpable in numbers such as ‘Se la doglia’ in which the unaccompanied imitative entries blossom into fertile pairings in thirds. In ‘Fabricator d’inganni’ animated verses contrast with a slower refrain, and instrumental interludes lend further expressive import. Often one longs for more. A folksy relaxation marks the start of ‘Amor la Donna mia’, and though the emotional temperature quickly rises, the tenor and bass seem suddenly to be cut off. ‘Io rido amanti’ begins like a ‘conventional’ balletta, then twists and turns wrong-footing the listener: rhythms are held back and then rush forth in a spin of notes; individual voices ripple through the ensemble sprinkling splashes of colour and personality. Again, all this in a little over one minute of music.

The solo items make an equally compelling impression. In ‘Tu, che pallido essangue’, from the 1612 Libro primo di arie passeggiate a una voce con l’intavolatura del chitarone, baritone François Joron’s introspective sentiments are darkened by pungent false relations and the arioso is richly expressive above dark instrumental timbres. In the melismatic diminutions of the close, the voice seems to lose itself, meandering above the pedal bass, before a final piercing dissonance conveys the pain wrought by hope: “Far al mio caro ben dolce ritorno” (And if I do not die, it is because I hope, one day, for a sweet reunion with my sweetheart.)

‘Occhi soli d’Amore’ is a particular highlight. Introduced by the harp’s tumbling conclusion to the strings’ dialogue, soprano Caroline Arnaud sings with bright, clear directness, the simple cantando style made more sophisticated by the voice’s flickering diminutions and chromatic shadings. “Già mi manca il vigore/ Già mi comincio à languire, Già mi sento morire” slips and slides, then fades, before a defiant assertion: “Ch’amoroso digiun non soffre il core.” (Already I lack strength, already I begin to languish, already I feel myself dying, For the heart cannot endure lack of love.) The concluding declaration, “E morendo v’onoro” (And in dying I honour you), has persuasive rhetorical authority. The simple villanella text of the lullaby ‘Figlio dormi’ is refined by Arnauld’s and theorbist Thibaut Roussel’s artistry, and Antoine Touche’s viola da gamba interlude makes time stand still, the sweet, relaxed melody spinning with eloquent freedom.

The instrumental items are similarly diverse. ‘Uscita’ from the fifth book of villanellas of 1630 is a busy, but fresh and clean, dance for violin and viola da gamba. The theorbo Passacaglia from the 1640 Libro quarto d’intavolatura di chitarrone throbs with rhythmic strength and dynamism, while ‘Colascione’, from the same book, riffs with an astonishingly modern vibe! Frissons from the individual voices make the Sinfonia No.13 shiver from within the rich textures. From the same 1615 collection, the longer Sinfonia No.9 feels exploratory and free, revolutionary even, but gentility always prevails.

After the trials and torments, the album closes with harmony – nuptial and musical: ‘Se turbando Austro le stelle’ from the Coro musicale (1627) which celebrates the marriage of Don Taddeo Barberini and Donna Anna Colonna. As the two hearts of Anna and Taddeo are bound together in one, the alternating pairs of voices unite sweetly, exuberant triple-time duets settling into light, duple-time concordance.

The album booklet contains a brief but engaging biography written by Anne Marie Dragosits, author of the first detailed account of the composer’s life, Giovanni Girolamo Kapsperger, ‘ein ziemlich extravaganter Mann’ (2020). The song texts are presented in short sequences, in Italian, with French and Italian translations following (the formatting of the digital version is sometimes confusing), though there is no discussion of the individual works or the collections from which they are drawn. Norac’s ‘The Kapsberger Affair’ is printed in French, but there is no translation.

The connection between Giovanni Girolamo Kapsberger: Il tedesco a Roma and ‘The Kapsberger Affair’ remains elusive, but perhaps that’s fitting for a composer the details of whose life are largely unknown. What intrigues here also delights: the musicians of L’Escadron Volant de la Reine get ‘inside’ Kapsberger’s music and, performing with vitality and flair, reveal its riches if not its secrets.

Claire Seymour

Giovanni Girolamo Kapsberger: ‘Il Tedesco’, Rome 1610 – Madrigaux, villanelles & autres airs

L’Escadron Volant de la Reine: Caroline Arnaud (soprano), Eugénie Lefebvre (soprano), Damien Ferrante (countertenor), François Joron (baritone), Renaud Bres (bass), Josèphe Cottet (violon), Antoine Touche (viola de gamba), Thibaut Roussel (théorbe), Caroline Lieby (harp), Clément Geoffroy (harpsichord and organ)

harmonia mundi HMM902645 [64:35]