Sometimes, less really is more. Such was confirmed by this powerful and affecting concert performance at the Barbican Hall of Beethoven’s lone opera, Fidelio, by Laurence Equilbey’s Paris-based Insula orchestra & accentus choir. Equilbey and director-designer David Bobée have eschewed concept in favour of communication. So, we had no tonal lurch such as heightened the dramatic incongruity of the two acts in Tobias Kratzer’s production for the Royal Opera House in 2020. Nor, as Frederic Wake-Walker misguidedly proffered at Glyndebourne in 2021, a panoply of visual and narrative interventions – a new spoken text, a new character and and cinematic hyperactivity – designed to turn Beethoven’s singspiel into a political-philosophical manifesto. Instead, in this interval-free performance, Equilbey and Bobée offered a minimalism which made the opera feel modern, its conflicts immediate and real. And, the lack of clutter – literal and conceptual – created space for the energy within the music to be released, driving a human drama that was consistently credible, moving and direct.

Performed three nights earlier in the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels, this Fidelio travels to La Seine Musicale in Paris for three fully staged performances on 14th, 16th and 18th May. At the Barbican, Bobée had only costumes – grey boilersuits, uniforms and prison rags – lighting and limited movement around the Insula orchestra, who were centrally placed, with which to work. That the drama was so compelling attests to the director’s discernment and the clarity of his vision. Characters were sometimes placed at opposite ends of the wide stage, or dispersed around the orchestra, emphasising the bewildering solitude in which their moral choices must be made. Contrastingly, the shared pity felt by Rocco, Leonora, Marzelline and Jacquino for the prisoners whom they must usher back to their cells at the end of Act 1 was emphasised by their position, in a line, at the front of the stage.

Subtle dimming and intensifying of the lighting persuasively heightened the dramatic colour, too. The shadows cast over the Prisoners during ‘O Welche Lust! matched the slightly subdued and gentle quality of their chorus of wonder at their temporary freedom – the accentus chorus were stunningly refined – as if their hope, though not extinguished, was but fragile. This was no joyful exaltation, and was less sentimentalised for it. In contrast, the strength of the illumination which exposed the ailing Florestan in his dungeon cell suggested that the true light shone within him, penetrating and defeating the darkness of the regime which imprisons him.

Equilbey’s period-instrument ensemble overflowed with energy and colour. The overture (the last of Beethoven’ four efforts) was rather untidy but thereafter Equilbey combined rigour with flexibility, tensing her shoulders, leaning forwards, bending low and garnering transparent textures and muscular rhythms. In Act 1 the ensemble sound was quite ‘Classical’, but the weight and richness deepened as the drama intensified. When we descended into the underworld grave at the start of Act 2, the music had a cold, gloom that chilled the blood, the bite of the natural horns and the terror of the pounded timpani strokes making their dramatic mark.

The opening buffa episodes seemed more natural and flowing than is sometimes the case, and the spoken dialogue (slightly trimmed by Beate Haeckl) also felt an innate part of the drama, rather than something tricky, to be negotiated rather than inhabited. Hélène Carpentier’s Marzelline was a complex, sensitive character, not merely a love-struck soubrette. There was a lovely brightness to her voice, a real asset in the ensembles, and her graceful phrasing brought out her sympathetic qualities, as well as making her both sensual and sincere. As Jacquino, Patrick Grahl was her well-matched sparring partner, his warm, buoyant tenor capturing the youthful, playful optimism of the rejected suitor.

Christian Immler was a persuasive Rocco. The ‘gold aria’ can slip into buffo territory, but there was a focused conviction about this father’s advice to the affianced youngsters. Immler convinced that this Rocco was a man of conscience, grappling with moral dilemmas, pragmatic but self-scrutinising. There was genuine pathos in his feelings for Florestan and a certain nobility in his responses to the situation in which he found himself. In contrast, I found Sebastian Holecek’s Don Pizarro rather too much of a stage villain: as he wielded his dagger aloft, with cries of “Vengeance is mine!”, he seemed a crazed – blackly comic – dictator drunk on his own authority, and we have rather too many of those in real life at the moment. There is a terrific darkness in Holecek’s resonant baritone, but his portrayal didn’t make me tremble, and ‘Ha, welche in Augenblick!’ lacked the emotional rawness that it can achieve.

Anas Séguin’s Don Fernando arrived like an angelic deux ex machina from the rear of the stage, his white cloak spread wide like rays of heavenly light. If there was a danger that this Fernando would be a two-dimensional emblem of benevolence rather than a real human envoy to remind us of the King’s command and care, then the firm hug that he shared with the released Florestan, and the instrumental military punch, kept that risk at bay.

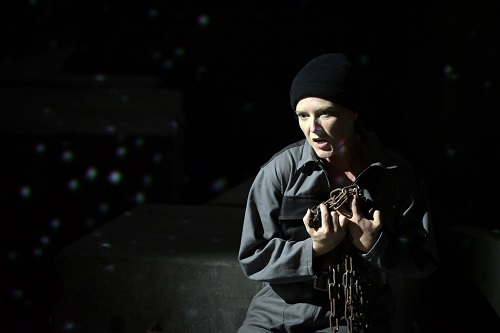

In the roles at the centre of the drama, soprano Sinéad Campbell-Wallace and tenor Stanislas de Barbeyrac gave truly engaging performances. As the ragged, righteous captive, Barbeyrac made a gripping entrance from the rear of the stage, issuing a cry, “Gott! Welch’ Dunkel hier!”, which shook the Hall and one’s heart, before a superbly controlled diminuendo seemed to evoke both the waning of Florestan’s physical strength and the persistence of his spiritual stamina. Barbeyrac sang ‘In des Lebens Frühlingstagen’ slumped on ground but this did not diminish his vocal power or dramatic presence, and the aria’s long, extended phrases posed no difficulties. His tenor had an easy strength at the top – it was warm and ardent in ‘Und spur’ ich nicht linde’ – as well as darkness at the bottom. Rounded and warm of tone, it’s a lovely voice, and he used it with great sensitivity.

Campbell-Wallace has a fairly light soprano, but it is generous of colour and strong across the range – her chest voice, which the role challenges, was powerful and rich. The Irish soprano affectingly communicated Léonore’s determination – the angular intervals of ‘Ich folge dem inner Triebe’ were flexibly shaped – and ‘Abscheulicher!’ conveyed a psychological depth that was absolutely persuasive. The conjugal bliss of the reunited pair was fervently expressed in ‘O namenlose Freude!’, but even at this emotional peak there were expressive subtleties that made the intensity feel ‘real’ and human.

For once, the Finale did not feel overly didactic. “Heil sei dem Tag, heil sei der Stunde!” the Prisoners celebrated, resonantly extolling the mercy and justice that have been enacted by the fulfilment of Léonore’s quest to liberate Florestan. But Equilbey and Bobée did not give us an ‘idea opera’. Rather, this Fidelio was a drama about people, their encounters and experiences, their trials and triumphs. It made clear that Beethoven’s quest for the eternal ideal of truth, goodness and beauty can only be fulfilled through collective human endeavour and compassion. As Don Fernando declares, “Es sucht der Bruder seine Brüder, und kann er helfen, hilft er gern” (A brother seeks his brothers and gladly helps, if he can). A lesson for our times.

Claire Seymour

Beethoven: Fidelio

Florestan – Stanislas de Barbeyrac, Léonore – Sinéad Campbell-Wallace, Don Pizarro – Sebastian Holecek, Rocco – Christian Immler, Marzelline – Hélène Carpentier, Don Fernando – Anas Séguin, Jacquino – Patrick Grahl, First Prisoner – Lancelot Lamotte, Second Prisoner – Matthieu Heim; Director – David Bobée, Conductor – Laurence Equilbey, Assistant director – Nicolas Girard-Michelotti, Costume designer – Sabine Siegwalt, Insula Orchestra, accentus choir (Choirmaster, Marc Korovitch).

Barbican Hall, Barbican Centre, London; Wednesday 11th May 2022.

ABOVE: Stanislas de Barbeyrac (Florestan) © Vincent Pontet