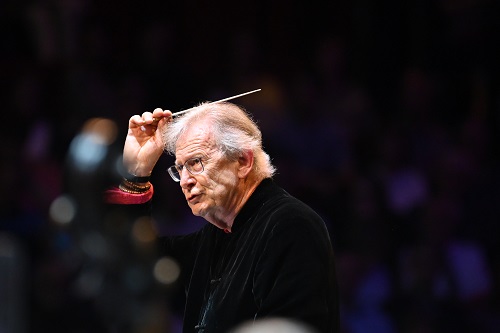

John Eliot Gardiner surely named his Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique with an intent that was thrillingly in evidence during this performance of Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis, the instrumentalists being joined by the Monteverdi Choir in full and fabulous voice and a superb quartet of soloists – soprano Lucy Crowe, mezzo-soprano Ann Hallenberg, tenor Giovanni Sala and bass William Thomas.

Gardiner has shown in performance and recording that his approach to the Mass is an invigorated and bold one, fierce even. Here, his tempi were characteristically impetuous, the dynamics extreme, as if to emphasise both the love and the terror within the work – the passion and intensity of Beethoven’s faith, the drama and conflict of his inner struggles bared in sound. While some may prefer a less provocative interpretation, Gardiner’s commitment to his vision, his complete certainty, held together a work of huge dimensions and complexity, which breaks the conventional boundaries of the sacred form and which, with a less sure guide at the helm, can sprawl apart. Force and fire did not obliterate detail though, and even at the most breakneck tempi the choral and instrumental counterpoint was crystal clear, the articulation precisely defined. Beethoven pushes his singers hard and high, but the choral intonation was unfailingly secure – and the soprano tone at the top beautiful. Gardiner knew that he could take his musicians with him. With a red glow illuminating the rear of the Royal Albert Hall, this performance did indeed seem revolutionary.

The orchestral opening to the Kyrie had breadth – space to hear the details and the different types of accent and emphasis that Gardiner drew from his players – but it was always moving forwards, opening up to gradually fill the ‘nave’ of the Royal Albert Hall. The first choral entry made a tremendous impact, the rhythm of the text-setting creating energy. The solo interspersions, layering of the choral parts and the transition to the Christe eleison were all seamlessly managed, and when the Kyrie returned it felt as if it had gained further power and weight from the accruing pleas.

The Gloria was rocket-fuelled, soaring with a glorious shine, the repetition of emotive words packing a real punch. ‘Et in terra pax’ brought sudden calm, with no loss of momentum, then the roaring trumpets lifted the voices in adoration, ‘Laudamus te’. ‘Adoramus te’ was a whisper of reverence. The choral fugatos were impressively precise, harmonically so rich but scrupulously detailed horizontally. The interplay between the soloists and choir in ‘Gratias agimus’ suggested that even in moments peace, the elation of faith could not be suppressed, and if ‘Qui tollis peccata mundi’ was solemn, the sopranos of the Monteverdi Choir made their sustained top Bs shine richly. It’s a mammoth movement, but the singers’ rhythms remained taut and the counterpoint agile as Gardiner drove towards and through the ‘Gloria in excelsis Deo’, the punctuating ‘Amens’ adding to the increasing pace and jubilation. No one could be in doubt of Beethoven’s Catholic faith.

And, so, the Credo began with confident, expansive statements, ‘Credo in unum Deum’, the ensuing profession of belief never sounding doctrinal, always personal. A sense of wonder infused the low voices and strings’ quiet utterances, ‘Et incarnatus est’, while the ‘Crucifixus’ fairly throbbed with suffering, the stabbing trombones puncturing the soloists’ sensitive enunciation of the text. The image of Christ’s burial sank to the barest whisper, but the tension was exploded by the almost frighteningly intense cry of amazement and joy, ‘Et resurrexit’, the choral voices surging through their rapid rising motifs, driven forward by vigorous timpani and busy strings. The delicacy with which Gardiner placed the opening, repeated notes of the final phrase, ‘Et vitam venturi saeculi’, was touching, but he used the repeating motif to build a flowing force into the crowning melismatic ‘Amen’s.

The orchestral prelude to the Sanctus had a lyricism and calm worthy of Beethoven’s score marking, ‘with devotion’, but the solo quartet brought animation, through their articulation, to ‘Dominus Deus Sabbaoth’, and ‘Pleni sunt’ was fast and gleaming. Veneration returned in the Praeludium: this was especially lovely woodwind playing, though leader Peter Hanson’s violin solo didn’t carry all that well to my seat in the stalls.

And so, we arrived at the lengthy Agnus Dei, with its alternation between prayer for what Beethoven called ‘inner and outer peace’ and vivid musical images of militarism. The choral lines grew in vigour through ‘Dona nobis pacem’, but the arrival of the beat of war was fittingly aggressive and jarring – the orchestral colours almost too bright and the rhythms tensely muscular, suggesting the pitifulness of man’s failures in the eyes of the divine to whom they appeal.

The solo quartet, positioned stage-left behind the orchestra, were exemplary, though only soprano Lucy Crowe sailed effortlessly across the massed musicians. She gleamed in the Christe eleison, in which the soloists’ melismas were expressive and impassioned, and her sustained high notes in the Benedictus were beautifully clean and legato. Giovanni Sala sang with wonderful colour and strength throughout, and the tenor solo in the Credo, ‘et homo factus est’ was warm and earnest. William Thomas found a solemn tone at the start of the ‘Agnus Dei’, his bass full of feeling, with dark colours at the bottom. Beethoven keeps the soprano silent at the start of this movement and here Ann Hallenberg’s enunciated of ‘Miserere nobis’ was notably charged with emotion.

The Missa Solemnis ends with a plea, ‘Grant us peace’ – an end to war and to what David Cairns described in his erudite and engaging programme article as ‘the whole senseless ferocity of the human race’. The glorious tone of the Monteverdi Choir’s final ‘Dona nobis pacem’ seemed even more poignant at this present time.

Claire Seymour

Beethoven: Missa Solemnis

Lucy Crowe (soprano), Ann Hallenberg (mezzo-soprano), Giovanni Sala (tenor), William Thomas (bass), Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique, Monteverdi Choir, John Eliot Gardiner (conductor)

Royal Albert Hall, London; Wednesday 7th September 2022.