Poets from W.H. Auden to Shakespeare and Goethe to Racine fired Benjamin Britten’s musical imagination and kindled an artistic response that had little equal among 20th-century British composers. Nowhere do we see his taste in literature more clearly than in the two related orchestral song cycles, the Serenade and Nocturne. This disc brings together eleven English writers, not forgetting the Frenchman Arthur Rimbaud for Les Illuminations. P eter Pears, for whom both these works were intended, was a further creative stimulus for Britten, but it was the Swiss soprano Sophie Wyss for whom Les Illuminations was originally conceived. All three works have a well-trodden discography and appear together in two celebrated recordings by Pears and versions by Ian Bostridge, John Mark Ainsley, Adrian Thompson and Martyn Hill. While it may be difficult not to ‘hear’ these singers (and some remarkable horn players) in this recording, this recent version from Andrew Staples, and the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra under its artistic director Daniel Harding brings ample rewards. Not least is the superb musicianship of the orchestra’s solo horn Christopher Parkes.

Andrew Staples’ undemanding, easy-on-the-ear tenor provides close attention to every textual detail, yet nothing is over-wrought, mannered or over-enunciated. In Rimbaud’s collection, Staples glides effortlessly over the semiquaver runs in ‘Marine’ (not something Pears does with any conviction) and tops a lovely high B-flat pianissimo in the closing bars of ‘Phrase’. There’s never any sense of strain; Staples is incapable of producing a coarse, ugly sound. Everything is beautifully manicured, so much so at times that a listener might soon forget the ‘savage parade’ within ‘Villes’ or the supposed sarcasm Britten wished for in ‘Royauté’. Vocal shading is generally excellent, as is his virtuosic technique. Intonation is unimpeachable and diction impressive too, but one might wish for more timbral differentiation especially within the fantastical imagery of ‘Villes’. Yet I admire the disembodied tone for ‘Interlude’ and the almost chaste, erotically charged ‘Being beauteous’ where Staples floats the voice with such natural control. Daniel Harding exercises well-judged control over the strings of the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra, and their variously athletic, crisp and sonorous tone is fully captured by harmonia mundi’s microphones.

Scarcely less sonorous is the horn playing of Christopher Parkes in the Serenade, a work immediately recognised as a masterpiece in 1943 and recorded a year later with Pears, Dennis Brain and the Boyd Neel String Orchestra under Britten. Colourful imagery and sensuous images in Les Illuminations are now superseded in the Serenade by insidious dreams and the loss of innocence. The work’s dedicatee Edward Sackville-West observed, “The subject is Night … the lengthening shadow, the distant bugle at sunset, the Baroque panoply of the starry sky … but also the cloak of evil”. The latter is disturbingly evoked in the chromatic worm of ‘Elegy’, Parkes’ unsettling horn the central protagonist and Staples’ suitably chilling voice summoning Blake’s “dark secret love”. Charles Cotton’s ‘Pastoral’ is eloquently rendered, its languor nicely achieved in its opening dolcissimo, Staples’ perfectly enunciating the closing phrase “shall lead the world the way to rest”. ‘Nocturne’ (‘The Splendour falls on castle walls’) is a satisfying mix of brilliance (razor-like strings) and nostalgia with well contrasted nobility and wistfulness. Elsewhere, the journey of the soul from earth to purgatory, found in the anonymous 15th-century ‘Dirge’, is well charted by Staples, who turns up the emotional heat to sound increasingly unhinged. Both soloists are suitably nimble in ‘Hymn’, scale figures dashed off with assurance, the soloist singing with an awed wonder to the Goddess Diana. There’s some deft mixing of vocal registers in Keats’ sonnet where the healing power of sleep is exquisitely communicated. Parkes shapes the melodic contours of the outer movements with great skill, the horn’s natural harmonics at the opening invoking Britten’s admiration for Gustav Mahler.

Mahler’s wife, Alma, was the dedicatee behind the through-composed Nocturne (1958) which, like the better-known Serenade, is a cycle of night poems (Shelley, Wordsworth, Keats and Shakespeare) for tenor, seven obbligato instruments and strings. As an extended meditation on dreams and moonlit enchantment (held together by a recurring ritornello figure in the strings), it picks up the theme of the last song of the Serenade, Keats’s sonnet, ‘To Sleep’. Staples is equally comfortable in these melodically leaner settings, powerful in the nightmare-visions of Britten’s setting of Wordsworth’s French Revolution-inspired The Prelude, and delicate in Coleridge’s The Wanderings of Cain. His sense of reverie convinces in Shelley’s opening poem, so too his desperation in Tennyson’s The Kraken (writhing bassoon especially graphic) and gossamer light in Thomas Middleton’s haunting ‘Midnight Bell’, where Parke’s horn provides all manner of bell-like sonorities. Wilfred Owen’s bitter The Kind Ghosts inspires a detached, trance-like delivery from Staples, impish in Keats’ Sleep and Poetry and accepting in the Mahler-influenced Sonnet 43.

For those dedicated to Bostridge, Hill or Pears, this triptych may present few surprises, but this disc offers polished, well-balanced performances that vividly convey Britten’s artistic vision with outstanding musicianship from Harding and his collaborators. Full texts, translations and informative notes are included.

David Truslove

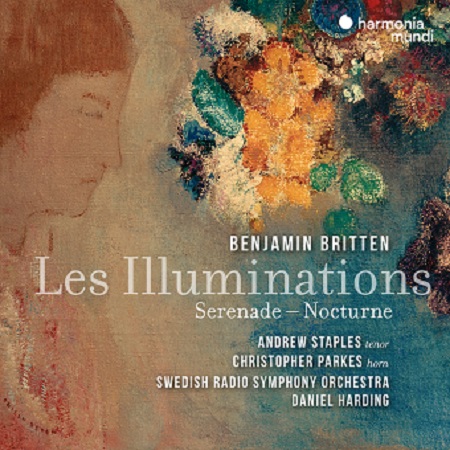

Britten: Les Illuminations Op.18, Serenade Op 31, Nocturne Op.60

Andrew Staples (tenor), Christopher Parkes (horn), Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra, Daniel Harding (conductor)

harmonia mundi HMM 902267 [74:07]