Gioachino Rossini finished Otello in 1816, the same year as his comic masterpieces, Il barbiere di Siviglia and La Cenerentola. The latter two are acknowledged masterpieces. Yet it is Otello that marked a turning point in Rossini’s own work – and the history of opera.

For the next decade and a half, Rossini would devote himself almost exclusively to tragedy, for which he crafted a new style of operatic expression. One hears these innovations in Otello’s score. The first act is packed with bubbling major-key bel canto numbers more similar to his comic works and thus unsuited to tragic melodrama. In Act II, however, Rossini intensifies the dramatic tension, recasting bel canto style in a more powerfully conflictual manner. Otello and Rodrigo, rivals for Desdemona’s hand about to fight a duel, fling high C’s and D’s at one another like violent sword thrusts. A distraught Desdemona sings something akin to a “mad scene,” filled with wild, nearly unsingable, vocal roulades. Act III takes a further step into the 19th century. Rossini simplifies the musical textures to afford insights into psychological and to portray naked brutality. Desdemona’s Willow Song and prayer is asymmetrical reverie, Otello’s subsequent recitative is grimly resigned, and his stabbing of Desdemona is a shockingly quick denouement.

mezzo-soprano Sun-Ly Pierce as Emilia.

Rossini’s innovations showed the path that Meyerbeer, Donizetti, Bellini, Verdi and other Italianate composers would explore over the next century. Now that Verdi’s eponymous opera has eclipsed that of Rossini, the latter’s may seem staid. Yet in Rossini’s day it was revelatory – and not just musically. For example, Otello was the first opera to show murder or suicide on stage – something to the censors objected to so strenuously that they imposed on early performances an incongruous happy ending in which the protagonists live happily ever after – fortunately, not longer in use.

Even more than most bel canto operas, Otello relies on great singers who can surmount difficulties with ease, improvise ornamentation at will, and convey pathos while doing so. In the 19 th century, it attracted Giuditta Pasta and other superstars; and its revival a generation ago attracted the likes of Federica von Stade, Cecilia Bartoli, Anna Catarina Antonacci, Montserrat Caballé, Jose Carraras, and Samuel Ramey.

Today, a new generation of singers have made the opera their own. Foremost among them is Lawrence Brownlee, a global superstar coloratura tenor, whom Opera Philadelphia secured for the fiendishly difficult role of Desdemona’s conventional suitor Rodrigo. Verdi suppressed this character entirely. Yet Rossini’s adaptation focuses not so much on Otello’s changing psyche or Iago’s evil machinations, but rather on Desdemona’s effort to overcome parental and social opposition to her love for Otello. This places Rodrigo’s pleas to her and his direct confrontations with Otello at the center of the drama.

(Khanyisa Gwenxane).

Brownlee owns this role today. His technical command was marvelous: every note clear, even, well-pitched, and even from top to bottom. Whereas most tenors in this repertoire stress the soft side of the rejected lover, Brownlee’s brassy tone, crisp articulation and perfect Italian diction not only filled the house but bolstered Rodrigo’s presence and power as a character.

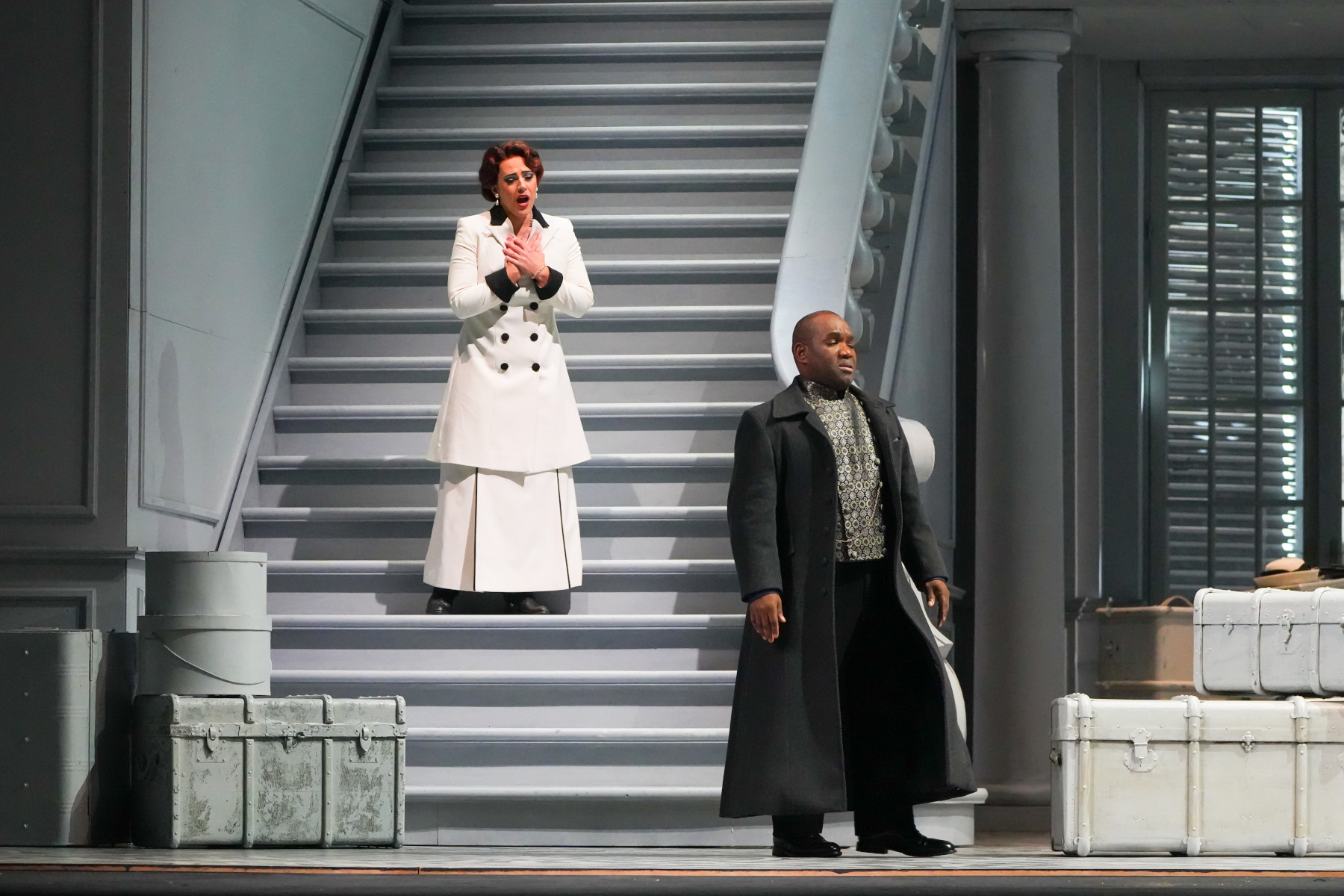

Brownlee’s extraordinary vocal charisma posed a challenge to everyone else on stage – yet all adapted in ways that, in the end, exceeded the sum of its parts. Young South African Tenor Khanyiso Gwenxane, who has been laboring in provincial German houses, still needs to develop the vocal ease, weight and range, particularly at the bottom, to command the stage and convey Rossini’s subtly differentiation by timbre of the three lead tenor roles, whereby Otello is meant to have the more heroic timbre. Nonetheless, he husbanded vocal resources and exploited opportunities cannily, creating some compelling moments in the final act.

Alek Schrader, a bel canto tenor who came to prominence fifteen years ago by hitting nine high C’s in the Metropolitan Opera competition, gave a memorably intelligent portrayal of Iago. Eschewing vocal pyrotechnics for serpentine legato, subtle rubato and convincing acting, he underscored the villain’s duplicity and charm.

Argentinian mezzo Daniela Mack brought considerable experience in major houses across Europe and the US. Despite the occasional lack of vocal precision, evenness and weight in the lower register, she sang fearlessly, convincingly portraying Desdemona’s passionate but futile struggle to avoid her fate. Sun-Ly Pierce brought vocal freshness, dramatic immediacy and, at times, surprising power, to the important role of Emilia, creating a perfect balance to Mack’s heavier Desdemona.

(Lawrence Brownlee).

Rising Californian bass Christian Pursell, who today sings small parts in big houses and big ones in smaller ones, was (for me) the surprise of the evening. The secondary role of Desdemona’s father Elmiro rang forth with impressive power and clarity. This voice has real potential; I would like to hear it again.

Italian Maestro Corrado Rovaris conducted with verve. With more rehearsal time, perhaps the recitatives – essential in this opera – could have been shaped more imaginatively. Spanish director Emilio Sagi’s unit set, borrowed from a company in Belgium, eschewed more expressionistic displays in favor of an attractive tableau that reflected sound well and did not distract from the singers. Only his curious decision to display Desdemona’s dead body throughout the final scene, rather than suddenly revealing it at the final moment, seemed to rob the evening of a proper melodramatic conclusion. The audience responded with an enthusiastic ovation – clear validation of Opera Philadelphia’s bold decision to program this rarely performed masterpiece.

Andrew Moravcsik

Otello

Music composed by Gioachino Rossini.

Libretto by Francesco Berio di Salsa after William Shakespeare’s play Othello, or The Moor of Venice.

Cast and production personnel:

Otello: Khanyiso Gwenxane; Desdemona: Daniela Mack; Iago: Alek Shrader; Emilia: Sun-Ly Pierce; Elmiro: Christian Pursell; Gondolier: Aaron Crouch; Lucio: Daniel Taylor; The Doge: Colin Doyle. Conductor: Corrado Rovaris. Director: Emilio Sagi.

All photos by Steven Pisano courtesy of Opera Philadelphia.

Above image: Khanyiso Gwenxane as Otello.