Film music has long been a theme of classical concerts – although this sold-out concert given by the London Philharmonic Orchestra and Edward Gardner was just a little different. It was devoted to a single film and was not in the least bit what most people might be describe as easy music. But then, the Proms never ceases to amaze me; these days, capacity audiences stay for Xenakis too.

The film was Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 2001: A Space Odyssey and the music by György Ligeti and Richard Strauss – most of it by the Hungarian, in fact. I do, perhaps, start from a distinct disadvantage from most of the audience – I have never seen Kubrick’s film; most science fiction has, whether it be literature or film, never appealed to me, and nor did I ever want to fly into space when I was a child. But even if I can’t tell you how Kubrick used Ligeti’s music I can see the appeal of it (and his apparent willingness to irk the composer by using much more of it than intended). Ligeti’s Requiem is a particularly austere, disconnected work; it can also sound extraordinarily desolate and sepulchral. There are voids of emptiness throughout the score; language which becomes unintelligible. There are few requiems less overtly human in scale than this one; conversely, there are few Kubrick could have chosen that were more suitably alien than Ligeti’s.

Ligeti was a composer of colour – but he was also one of extremes of dynamic range and this is where the Requiem becomes quite problematic in an acoustic like the Royal Albert Hall. Ligeti can let his soloists – just a soprano and a mezzo-soprano – become unchained from the rest of the orchestra and chorus, almost as if they themselves are just floating in space. It isn’t, of course, that they shouldn’t do this – it’s at the sheer imperceptibly of audibility that Ligeti does it making them sound completely lost. In a smaller acoustic they sound as if they can be rescued; in the Albert Hall it was a little like they were at risk of never coming back. That they do is because of a solo flute – here as piercing as an arrow – which has anchored them to the ground.

The ’Introitus’ itself begins breathtakingly slowly – where space seems limitless. This does seem to work in the vast globe of the Albert Hall where the deep resonance of the basses and trombones is like a pyroclastic explosion. It’s in the ‘Kyrie’ that Ligeti takes us into hell; this not an especially Dantean vision of it, there are no circles of horror waiting for us to surmount on our journey through it. Rather, Ligeti uses his choirs to give us a vision of terror in a very modern, descriptive way. In a sense they are in chaos – the very form Ligeti uses is unstructured, as the choirs split into clusters. They seem like planets revolving around the orchestra, every meaningful word now shattered into a meaningless mass of sounds, liquid rather than precise.

The ‘De die judicii sequentia’, rather like Verdi’s ‘Dies irae’, is the Day of Judgement. The music is taken at quite some pace – like a meteorite flashing across the sky. There is no shortage of virtuosity required from the two soloists, either. Both climb to their highest registers as they are forced to compete against an orchestra at war on stage; it’s one of the rare times in the Requiem where Ligeti marshals his forces against the vocal forces into some kind of galactic battle. If you always get the sense of religious fervour in Verdi, with Ligeti the tendency is towards the triumph of atheism, or at best agnosticism. What is natural in Verdi is forced in Ligeti; if there is the hope of salvation in Verdi, only damnation awaits in Ligeti.

The final ‘Lacrimosa’, taken very slowly, is extremely empty and void – it has the sparseness of space with almost no sense there is anything beyond the limited scale of Ligeti’s dynamic range. Pianissimos abound, voices shake at tremolos only, the soprano and mezzo are alone in this permafrost. Ligeti’s Requiem ends where it began – at the very bottom of its orchestral register, without redemption.

The kind of performance this work deserves and the kind of one it receives are rather different things. Edward Gardner is first and foremost a man of the theatre, of the opera, and the London Philharmonic has retained under him that glorious, rather lugubrious at times, string tone which makes them such an expressive orchestra. This was too rich to be an ascetic performance – in part it lacked that Ligeti acidity, the feeling that this Requiem is in part persecution rather than religious in nature. It’s certainly true that one couldn’t have asked for a more penetrating sense of depth – when the trombones, or bass-clarinet played one did feel one was in the bowels of hell itself. Gardner knows how to float pianissimos of fragile gauntness – the bows against strings were sometimes as shallow as scratches on skin.

But perhaps Gardner’s great achievement was perhaps to make us not focus on the orchestra at all. This was a performance very much about the voices and especially the choruses. There were three of them – the Norwegian Edvard Grieg Kor, the London Philharmonic Choir and the Royal Northern College of music Chamber Choir. They were just outstanding. Ligeti makes none of the singing easy – from the unsynchronised singing in the ‘Introitus’, the complex sub-divisions and clusters in the ‘Kyrie’, the crossfire and salvos in the Day of Judgement and hollow tremolos of the ‘Lacrimosa’. All were mesmerizingly done, with striking precision. The two soloists, too, Jennifer France, the soprano, and Clare Presland, the mezzo-soprano, were both superb in parts which are demanding. Ligeti’s willingness to cast both adrift could have exposed weaknesses in their voices – but it showed neither soloist to have any. The imperceptible dynamics were audible from the stalls – just as their highest ranges came through thrillingly from an orchestra at full pelt. That scything edginess of their voices cut through like the sharpest of blades.

A magnificent performance, I think, and one also, perhaps, made a little more interesting by the intrusion at exactly 8pm on its dying chord by the ringing of a mobile alarm. I think Ligeti would have found this addition to his Requiem rather humorous – even if Edward Gardner clearly did not.

Another piece of Ligeti began the second half of the concert – his Lux aeterna, also used in the Kubrick film. This was performed by the Edvard Grieg Kor – and it was worth every Euro it cost to bring this superb choir to London. This is something of an icy work, but it is also luminescent, blazing and completely unlike the Requiem in any way at all – a particularly good reason why it should never be performed as part of that work. It also eschews any sense of the mortal in it.

In essence Lux aeterna is like a choral spider’s web – a chorus divided into the four conventional voice parts, each for four soloists, each of whom has a separate part: it becomes a 16-part polyphonic matrix of glorious complexity, colour, synchronicity and tempo. Designed also to be sung from a distance this was where the performance became truly spectacular (at least for the half of the audience sat on the right side of the Albert Hall – or most of the standing Prommers). With the hall plunged into darkness, only Edward Gardner on the podium and the choir – in the standing balcony – were spot lit, the choir between purple columns either side of them. That iciness melted, and became a beautiful vapour and spray of colour and sound that spread outwards in its cascading lattice before centring on a single locus. There was complete clarity from the choir here, a sharpness as if a spear had been thrown down towards its target. High notes and octaves rose through the mistiness and echoes almost unexpectedly just as with certainty the choir reached a silence with poised perfection. The whole experience of this performance had been sublime.

Richard Strauss’s Also sprach Zarathustra closed out the concert and was, I think, the most contentious of the three performances. I’m not sure that Edward Gardner is a born Straussian – or perhaps he feels less inclined to accept the provocations and temerity that Friedrich Nietzsche takes with the source material on which Strauss based this tone poem. The idea of the Übermensch (‘Superman’), or Aryan model, an early Nietzsche standard which he would later reject, and which Strauss conveys in his music only as a kind of evolutionary viewpoint of the human race from its origin, can overwhelm performances. Some performances are certainly more bombastic and more enthusiastic than others, especially those which have a creeping fascination with making Strauss’s music sound turbulent when it shouldn’t. Gardner, at least, accepts none of this drivel.

Also sprach Zarathustra does, of course, have one of the most celebrated – and colossal – openings in all music. It’s really difficult to make this opening sound understated but I think Edward Gardner’s problem here was that his orchestra was simply swallowed up by an organ that was closer to an exploding sun rather than a sunrise. This blip – although not the only one – certainly had nothing to do with the quality of the London Philharmonic’s playing; they were on superlative form, even better, in fact, than the Budapest Festival Orchestra which I heard two days later.

The LPO strings remain fabulous – rich, deep and yet extremely warm, too; more’s the pity that Gardner never really managed to make much of the cello entry into ‘Von der Wissenschaft’ then, the fugue itself just a tad square; but how spectacular were each of the first desk string players in their long theme of ‘Von den Hinterweltlern’ – the gloriously expressive cello, and sheer beauty of the first violin especially. This was world class playing. Gardner was at his best when the score was at its most sumptuous – the glittering waltz, for example. But there was no question that this was a triumph for the LPO’s brass as well – terrific trombones, airtight playing from the trumpets, and splendidly controlled horns.

Edward Gardner may have been a little unlucky in that none of the three works played ended in a way to give him a typical Prom ovation – but he also got that rare thing: the ability to control when the audience could begin their applause and this Gardner managed beautifully. There were many wonderful things in this concert in what is turning out to be one of the best seasons for many years.

Marc Bridle

György Ligeti: Requiem; Lux aeterna; Richard Strauss: Also sprach Zarathustra

Jennifer France – soprano, Clare Presland – mezzo-soprano, Edvard Grieg Kor (Håkan Matti Skrede – chorus-master), London Philharmonic Chorus (Neville Creed – chorus-master), Royal Northern College of Music Chamber Choir (Stuart Ovington – chorus-master), London Philharmonic Orchestra, Edward Gardner (conductor)

Prom 36: Royal Albert Hall, London; Friday 11th August 2023 (available on BBC Radio Sounds and

repeated on BBC Radio 3 on 24th August at 2pm).

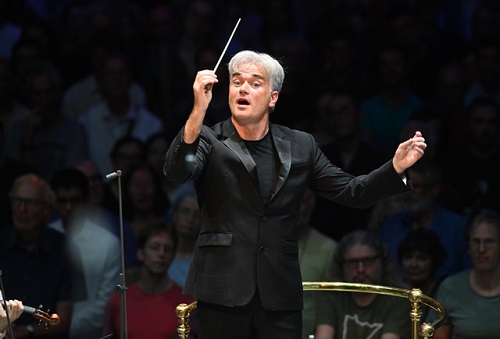

ABOVE: Jennifer France and Clare Presland, LPO conducted by Edward Gardner (c) Mark Allan