When you listen to a piece of music, performed live or on a recording, do visual images and visions sweep or fly through your mind, or fix themselves indelibly on your inner consciousness?

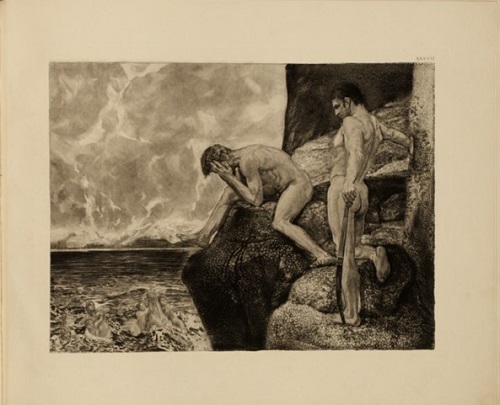

In 1894, graphic artist and sculptor Max Klinger (1857–1920) presented Johannes Brahms (1833-97) with his Brahmsphantasie: a monumental, illustrated book of the agonistic visions that the composer’s songs inspired within his artistic and psychological perception. He had declared in Malerei und Zeichnung (Painting and Drawing, 1891) that music, poetry, and the graphic arts were inimitably suited to subjective explorations of the ‘dark side’ of human existence. The 37 pages of the Brahmsphantasie (1888–94) comprise 42 engravings, lithographs, etchings, aquatints, mezzotints and drypoints which are interwoven with the music of five of Brahms’s lieder, alongside the piano-vocal transcription of the choral-orchestral Song of Destiny (1871).

Only five copies of the Brahmsphantasie were printed initially, in early 1894, though a second edition of 150 copies followed in October that year. Klinger’s images convey loss, terror, despair and destruction.[1] They were not intended as visual interpretations of Brahms’ music but as representations of the impact that it had on Klinger. The composer initially had doubts about this sort of ‘illustration’ of his music, but later wrote to Clara Schumann, ‘They are not really illustrations in the ordinary sense, but magnificent and wonderful fantasias inspired by my [vocal] texts’; and, to the Swiss writer Josef Viktor Widmann, ‘They are perfectly fascinating, and seem to be intended to make one forget all the miserable things of the world, and to life one into higher spheres’.

Maria Morton suggests that ‘[t]he Brahmsphantasie can be regarded as an interchange among kindred artists who interpretively transposed the mood and content of one medium into another’. Brahms dedicated his final work, Vier ernste Gesänge to Klinger, and thus these ‘Four Serious Songs’ made for a fitting climax to a recital programme exploring this year’s Festival theme, Art:Song – the way that the interdisciplinary dialogue between the visual arts, poetry and music unfolds in a wide variety of ways. Baritone Samuel Hasselhorn and pianist Markus Hadulla presented songs by Brahms and Schubert which traced ancient Greek and mythological themes, while some of Klinger’s illustrations were projected either side of the organ in Holywell Music Room.

This was in every sense of the word a ‘serious’ programme. The duo began with a sequence of five songs by Brahms, in which Hasselhorn displayed a very focused tone and taut delivery, often declining to soften the vocal line with the caress of vibrato. His tone was dark, the communication direct, unmannered and sustained. Diction was excellent. The recital began with Brahms’ ‘Alte Liebe’ which somehow coalesced intensity and dreaminess, the piano writing sometimes revealed as dense, elsewhere lightening. Hasselhorn was attentive to the imagery: there was a lovely vocal swell to convey the tangible, remembered scent of jasmine, even in the present absence of a bouquet, “Und habe keinen Strauß”. Also, a telling vocal intensification at the close, as the poet-speaker imagines how his ‘old dream’ leads him forwards – “Und führt mich seine Bahn” – the piano’s expressive postlude unfolding the pathway to the future.

‘Sehnsucht’ was certainly fully of yearning, both performers generating a sense of excitement, too, at the thought of beholding a vision of the ‘sweet, far distant maiden’. From the same Op.49 set, ‘Am Sonntag Morgan’ was infused with an indignant muscularity, but also anguish, the piano’s final plunge evaporating into the depths, evoking the poet-speaker’s sense of futility and frustration as he ‘wrings his hands sore when alone’ (“Um einsam dann die Hände wund zu ringen”). Hadulla’s right-hand explorations injected some tenderness into ‘Feldinseimkeit’. And, here Hasselhorn moved from restraint to release as the unceasing crickets wove ‘wondrously’ through the blue sky. However, the unexpected harmonies of the second stanza, and the inwardness of Hasselhorn’s expression, communicated the strangeness of the poet-speaker’s experience, drifting between the deep blue of the sky, happy dreams and death. ‘Kein Haus, Keine Heimat’ was a brief and intense close to the sequence, conveying the struggle expressed by Brahms in so many of these songs to reach a state of hopefulness.

Schubert provided the centre of the recital programme, as Hasselhorn and Hadulla ventured down some of the less frequently explored by-ways of the composer’s lieder oeuvre. We started with the familiar ‘Ganymede’, though, through which the duo built a persuasive impetus, the piano fluid and softening the occasionally sturdiness of the vocal line, but Hasselhorn confident and exultant at the top, particularly at the close. The high drama of ‘Prometheus’, majestic and heroic, and ‘Am Schwager Kronos’, relentless but never thunderous, were gripping. In the former, the baritone retreated from the rhetorical outburst of the opening, with the coming of the pained image of man’s misguidedness and vulnerablity – “wären/ Nicht Kinder und Bettler/ Hoffnungsvolle Toren” – while the later declamatory recitation was astutely punctuated by Hadulla’s penetrating harmonies, creating a tone of restlessness and questioning.

The chordal weight of ‘Grenzend der Menschheit’ (Limitations of Mankind) was fittingly oppressive, but the duo did not neglect the nuances, Hasselhorn again withdrawing and projecting his baritone in response to the expressive fluctuations of Goethe’s text, and traversing from floating ether to profound depths at the close, conveying the image of lives linked in an ‘endless chain of existence’ (“An ihres Daseins/ Unendliche Kette”). I was impressed by Hadulla’s responsiveness to the ‘last words’ that Schubert gives to the piano in ‘Memmon’, and to the way he injected drama in ‘Philoctetes’. The concluding journey to Hades (‘Fahrt zum Hades’) pulsed with triplet tensions and arrived at oblivion with rhetorical impact. Only a little more variety of vocal colour might have been desired.

So, then, what of those ‘Four Serious Songs’? Well, ‘Denn es gehet dem Mensche’ (For that which befalleth the sons of men) began with austere restraint, but Luther’s theological questioning unleashed rich cascades, celebrating humanist ideals. The unisons and tight intricacies of ‘Ich Wandte Mich’ (So I returned) revealed the duo’s shared vision as much as their technical prowess. And, for all the bitterness of the first stanza of ‘O Tod, wie bitter bist du’, Hasselhorn infused the final verse with sweetness and acceptance, his lovely head voice consoling those who have despaired and lost patience with life. His ability to traverse emotional extremes was impressive, even if at times his baritone felt a little light for the tortured utterances. ‘Wenn ich mit Menschen und mit Engelszungen redete’ was changeable of temperament; there was anguish and suffering here – there was to be no comforting conclusion to this thought-provoking and challenging recital. The overall impression was of total poise and assurance.

Earlier in the day, the Nigerian-American soprano Francesca Chiejina and pianist Jocelyn Freeman had been no less poised, during their lunchtime recital, Sketches of Homeland, though the sentiments expressed, and the moods indulged were – if not less intense – then perhaps ultimately more soothing. The duo opened their programme with Samuel Barber’s Knoxville: Summer of 1915, in which Chiejina’s lovely loose parlando style and the flexibility of Freeman’s rhythms conjured a heady perfume of nostalgia. But, the past and places were brought vividly into the Holywell Music Room, too. From the calm drift of quiet evenings on dusky porches, we were jostled into the jangling street of rolling, moaning streetcars. One might have liked a few more words at times, but in the dreamy reminiscences, Chiejina spun the most delicious high silky threads, while Freeman’s delicacy of touch was as beguiling as her vigour was enervating. Always there was a sense of demotic storytelling: whether through the folky or hymn-like motifs – there were tints of Copland here – or the duo’s relaxed slippage into Barber’s Italianate neo-Romanticism.

The remainder of the programme prompted and prodded one to sit up and listen! There were many unfamiliar works here, and much to appeal. Poulenc’s Cocardes comprises three settings of Jean Cocteau – ‘Miel de Narbonne’ (Narbonne Honey), ‘Bonne d’enfant’ (Nanny) and ‘Enfant de troupe’ (Child acrobat) – and was originally written for small ensemble of cornet, trombone, drums and violin. The title refers to the tricolour rosette, and these three ‘chansons populaires’ pay homage to the world of wandering minstrels and clowns. There was spriteliness, quirkiness and, in the last song, a lovely juxtaposition of military regularity and wriggling non-conformity, as Chiejina built to a richly glossy conclusion celebrating the audacity of the circus performers.

‘Le Souvenir’ by Henri Sauget was beautifully gentle and reflective. Shirley J. Thompson’s Psalm to Windrush: to the brave and ingenious,based on Psalm 84 (‘How amiable are thy tabernacles, O Lord’) reflected the anticipation and hopes of the Windrush generation through pulsing piano momentum and the impassioned vocal refrain, “And there you were Lord/ Your arms around us”. The vocal heights and fervour fully and inspiringly communicated the bravery and ambition, fortitude and faith, of those who migrated from the Caribbean to journey to the UK.

A pairing of two songs by Florence Price, ‘Night’ and ‘My Dream’, juxtaposed Straussian gloriousness – and Chiejina can venture low as well as high, can murmur and exult – with dancing fleetness. The portamento that Chiejina used to colour the rising major sixth at the very close of ‘My Dream’ was a mesmerising contrast to the dark riches of the preceding image of “Night coming tenderly/ Black like me”. Chiejina and Freeman concluded their box of delights with lyrical songs by Nigerian composers Laz Ekwueme and Ayo Bankole, in which the strength of feeling felt and conveyed was deeply touching, and the narratives transfixing.

After the evening’s ‘Brahms Fantasy’, many of the Holywell Music Room audience decamped to the University Church to experience Voice Trio and video artist Innerstrings collaborative concert-theatre piece, Hildegard Transfigured. Unfolding in a seamless hour of vocal intensity and visual kaleidoscopes, Hildegard Transfigured celebrated the 12th-century polymath’s visionary heights. The singing by this trio of sirens (Victoria Couper, Clemmie Franks and Emily Burn) was transfixing. Perhaps it was the late hour or the temperature in the church, but I was ‘en-tranced’ in all the best senses of the word.

The pristine vocalism – the memorising of the hour-long programme was a feat in itself – as well as the contrast of candlelight and digital Catherine wheels, and of ancient chant and newly composed interspersions by Laura Moody (setting fragments of Hildegard’s letters), culminated in the climactic ecstasy of ‘The Living Light’, the textual and musical repetitions almost overwhelming. It was the sort of experience that doesn’t really need any ‘analysis’ from the likes of critics such as me. One just needed to allow oneself to be engulfed by a miraculous musical embrace.

Claire Seymour

Sketches of Homeland: Francesca Chiejina (soprano), Jocelyn Freeman (piano)

Holywell Music Room, Oxford; Thursday 19th October 2023.

A Brahms Fantasy: Samuel Hasselhorn (baritone), Markus Hadulla (piano)

Holywell Music Room, Oxford; Thursday 19th October 2023.

Hildegard Transfigured: Voice (Victoria Couper, Clemmie Franks and Emily Burn), Innerstrings (video artist)

The University Church, Oxford; Thursday 19th October 2023.

[1] See Maria Morton (2022) ‘Max Klinger’s Brahmsphantasie: The Physiological Sublime, Embodiment, and Male Identity’, Nineteenth-century art worldwide, 21(1), for a detailed account of Klinger’s Brahmsphantasie.

ABOVE: Markus Hadulla and Samuel Hasselhorn