The Ashmolean Museum’s current special exhibition, Colour Revolution: Victorian art, fashion & design, aims to dispel the notion of the Victorian era as a bleak, black-and-white industrial age by revealing how new scientific breakthroughs inspired an explosion of colour – new hues, employed in new ways – in art and photography, dress and jewellery, and interior design. This evening concert in the Holywell Music Room by soprano Gweneth Ann Rand and pianist Simon Lepper presented a programme of songs which complemented the exhibition’s revelations, the latter elucidated and illustrated between the musical items by the museum’s Curator of Decorative Arts and Sculpture, Matthew Winterbottom.

The Ashmolean exhibits are eclectic, embracing paintings and drawings, stained glass and sculpture, manuscripts, artefacts, textiles and dyes, costume and accessories. In addition, there are examples of technological innovations such as William Henry Perkin’s accidental discovery of mauvine, the first aniline dye, and explications of other contextual influences, such as Charles Darwin’s theories on the use of colour in sexual selection and John Ruskin’s essays on the sacred nature of colour, both of which drew on Pre-Raphaelite ideas.

In his inter-music commentaries, Winterbottom gave a comprehensive impression of the exhibition’s scope and arguments. He compared Turner’s ‘Venice, from the Porch of Madonna della Salute’ (c.11835) with Whistler’s ‘Nocturne in Blue and Silver: The Lagoon, Venice’ (1879-80), the former artist a huge influence on Ruskin, who celebrated Turner’s brilliance as a watercolourist, the latter castigated by Ruskin for his abstract, subtle arrangements of colour and shape, his art charged with lacking form. Ruskin’s own influence was also explored, as well as the Pre-Raphaelites’ interest in reviving the luminous palette of the late-medieval age.

The links between the art and contexts explored and the music performed were more figurative than direct. It’s quite a leap to get from Queen Victoria’s black mourning attire (and the highly coloured costume that she wore for the 1745 Fancy Ball, on 6 June 1845, as painted by Louis Haghe (1806-85)) to the sometimes unsettling poems by W. H. Auden that Benjamin Britten set in On this Island (1936). Together with Thomas Dunhill’s setting of W. B. Yeats, ‘The Cloths of Heaven’ – sung here with hints of operatic grandeur – Britten’s songs formed the first part of the programme, titled ‘Queen Victoria and Prince Albert’.

“Let the florid music praise!” begins Britten’s opening song, a phrase which seems tailor-made for the sumptuousness of Gweneth Ann Rand’s soprano and the focus of her projection. Rand’s voice is plush and warm, and she brought an almost Handelian vigour to the declamatory statements, then rippled magnificently through the melismatic bravura, “Let the hot sun shine on”. The twisting, tripping phrases of ‘Now the leaves are falling fast’ were an agitated whisper above Lepper’s tensely pulsing chords but the calm final stanza, which extends the brief piano introduction, had a more dreamy, even visionary, quality. And, the image of the mountain’s “white waterfall” which “could bless/ Travellers in their last distress” was beautifully sustained, sculpted with superb vocal control.

Lepper’s delicacy of touch and subtle expressive nuances were impressive in ‘Seascape’, complemented by Rand’s expansive arches. ‘Nocturne’ brought a fresh simplicity, which Lepper coloured beautifully, while Rand brought a lightness and liquidity to the vocal line, the rhythmic regularity conjuring the vision of the earth spinning slowly on its axis as “through night’s caressing grip/ Earth and all her oceans slip”. The low monotone parlando of the closing episode allowed Rand to display the strong range of her substantial soprano and hinted at the darkness in these poems, the piano almost seeming to growl in response to the “revolting succubus”. Britten’s strange modulation, “Let him lie”, was touchingly enhanced by the quiet vocal rise, before the voice fell to the deep, “then gently wake”. ‘As it is, plenty’ danced along to Lepper’s spiky, swinging jolts, Rand’s glossiness building through the effusion of repetitions in the final stanza. The only thing might have wished for was more clarity of diction. Auden’s poetry hints, through complex imagery, at political concerns and private worlds, to which Britten’s music responds and which it elaborates: without the words, much is lost.

Winterbottom introduced some of the theories that developed about colour, from Keats’ fear that Newtonian science threatened to ‘unweave the rainbow’, destroying its poetry, to Georg Christoph Lichtenberg’s representation of the three-sided colour graph developed by the astronomer and mapmaker Tobias Mayer. Reflecting through musical means on Goethe’s ideas about the nature, function, and psychology of colours – that darkness is an active ingredient of colour, and the impact of different colours on mood and emotion – Olivier Messiaen’s Trois Mélodies followed.

Written when the composer was just 22 years of age, this was the only work in which Messiaen set one of his mother’s poems, framing it within two of his own. There were vivid changes of tone as the duo progressed through the three songs, which find the young Messiaen in Debussyan-vein. Lepper’s pianism was superb here: the lucidity of the introduction to ‘Le sourire’ was magical, and the unison of piano and voice flawlessly executed. Rand coloured the words sensitively in these songs (though a few more consonants would have been welcome, particularly at the start of words). I loved, though, the way she murmured the final words of ‘La fiancée perdue’ – “Donnez-lui le repos Jésus!” – capturing all of the song’s mystical elusiveness.

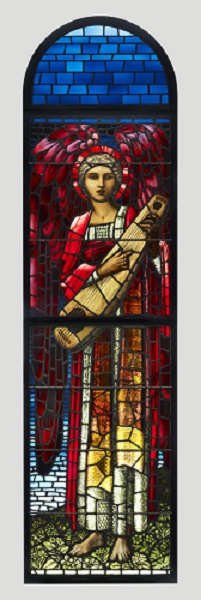

There was more mysticism – with an Irish hue – in the form of Samuel Barber’s Hermit Songs, Edward Burne-Jones’s ‘Angel with Zither (Dulcimer)’ (originally in the Haweis chapel, which was demolished in 1914, of St James’s Church, Marylebone) forming a vibrant backdrop on the wall of Holywell Music Room. In ‘At Saint Patrick’s Purgatory’ and ‘St. Ida’s Vision’, Rand and Lepper captured the spirit of solitude which pervades these songs, that latter lullaby concluding with wonderfully executed vocal rise which conveyed absolute spiritual conviction: “every night/ Is Infant Jesus at my breast”.

Rand’s complete emotional commitment to these beautiful songs – especially affecting in ‘The Crucifixion’ (“sore was the suffering borne/ By the body of Mary’s Son”) – and her communication with her audience were both intense and absorbing. I loved the way the piano’s motivic development in ‘The Heavenly Banquet’ deepened the anaphoric accumulations of the text, “I would like …”. The soprano used melodic gesture, such as the melisma which concludes the carillon of ‘Sea Snatch’ (“O King of the starbright Kingdom of Heaven!”) to evoke religious fervour. But, there was relaxation, too, as in the jittery, dreamy grace of ‘The Monk and his Cat’, and the aphoristic drollness of ‘Promiscuity’. The passionate climax of ‘The Desire for Hermitage’, particularly after the sparseness of the opening of the song, surely shook the walls of Holywell Music Room.

Discussion of Ruskin’s ‘Study at Dawn: Purple Clouds’ (1868) prefaced the final item of the programme, Claude Debussy’s Proses Lyriques, for which the composer wrote his own text and which exemplify the innovations informing his conception of the way verse and rhythm converse with melody and harmony. Rand and Lepper demonstrated a shared response to this unusual idiom which was both intuitive and sophisticated, conveying the suppleness and natural flow of melody and imagery. These elusive songs never ran away on their own imaginative flights. They formed an atmospheric and allusive conclusion to a thought-provoking and aesthetically satisfying evening of visual and musical exploration and enquiry.

Claire Seymour

Gweneth Ann Rand (soprano), Simon Lepper (piano), Matthew Winterbottom (speaker)

Britten – On this Island Op.11; Dunhill – ‘The Cloths of Heaven’; Messiaen – Trois Mélodies; Barber – Hermit Songs Op.29; Debussy – Proses lyriques L84

Holywell Music Room, Oxford; Friday 20th October 2023.