Having missed the three previous operas in this Ring Cycle I wondered if I’d find myself at a disadvantage in Regents Opera’s Götterdämmerung: the answer is, I think, both yes and no, especially when the narrative – indeed, largely the whole point of Wagner – is built on leitmotiv; it sometimes felt difficult to immediately connect with the past of this enormous production while focusing on simply the present. But these are still separate works, and Götterdämmerung’s blazing resolution tells its own story and introduces us to new characters along the way; on its own terms this was an enlightening and vivid performance, often superbly done.

There is, I think, a certain simplicity to this production which masks a much greater complexity. The three Norns arrive on stage for the Prelude – or within the Ring if we take the location literally – dressed in black and lift their veils before they begin their long narration of events that fill in vital gaps from the previous operas; only when Siegfried and Brünnhilde arrive on stage for act 1 proper, dressed in white, does the allusion to chess pieces come to mind (indeed, the concept of the ‘game’ seems everywhere in this production). For Gods and humans, Fate is but a game of manipulation and Götterdämmerung the point at which the pieces finally fall, and we meet checkmate: Valhalla is consumed in flames and the Ring is finally thrown into the Rhine.

Allusion is elsewhere, too. The Tarnhelm isn’t an object here; rather it’s an idea and it is reborn in Götterdämmerung when Gunther and Siegfried change identities (Siegfried succumbing to Gutrune adopting the form of Sieglinde, his mother). So intrinsically powerless is the Tarnhelm it shares a similar identity with the equally powerless Ring – these are ideas that add simply mythological essence to the story and little else. Likewise, when we are in Hagen’s Gibichung Hall this has become a museum of object d’art: Wotan’s broken spear (reduced to its tip), Mime’s saucepan, the fire extinguisher (a favoured method of death in this cycle) and so on – we have returned to the past of Walküre and Siegfried. Like much of this production the feel of it is both demotic and barren (in part necessitated by the finiteness of the space itself). The columns that symbolize Brünnhilde’s Rock double as Hagen’s Hall, with a singular one displaying the words “Du hast Nichts” – words which will come to have a final meaning at the culmination of the Immolation Scene when Hagen is thrown into Rhine by the Rhinemaidens.

Words are important in this production – from “Slayer” on the T-shirt of Siegfried to “Gesamtkunstwerk” inked on the back of Alberich. How much this is a “total work of art” is debatable given the resources and space available to Regents Opera but there is little question that in Gibichung Hall the arrival of the vassals summoned by Hagen reached a level of the theatrical that far extended beyond the operatic. At times this felt like Oktoberfest with vassals running into the aisles and eating popcorn and drinking beer on stage. True, it sometimes seemed a little hectic – a little busy – and Hagen often appeared lost in the commotion, but it had a bovver-boot malevolence to it, nonetheless.

And what of the Immolation Scene itself? Brünnhilde built her pyre off-stage, but I think one could interpret the burning of this Valhalla in both a literal and a universal sense. Everything about this Ring, and this Götterdämmerung is really no exception, is absolutely contemporary: we largely recognise Siegfried and Hagen as opposites not just because of the hero-villain dynamic, but because of how they dress in this production; it is not a million miles away from modern-day street warfare, nor tasteless street fashion (Siegfried’s silver trainers, for example). When Valhalla is finally consumed in fire the smoke seems to fill the entire hall – the glow of orange and red lights up the inside as if everything and everyone is caught within it. I think for a moment you are forced to think of the end of this Götterdämmerung beyond quite Wagnerian terms and take in everything that affects us today – and perhaps this is what makes the production ultimately so provocative. When the Rhinemaidens appear to throw the Ring into the Rhine it is not just Hagen who goes with it (disappearing into a trapdoor on stage) – so too does the column with “Du hast Nichts” written on it. Nothing more clearly sums up what the Ring is about – that at the end of its 16 or so hours there are no winners, and really no one ends up with anything at all.

The casting for this Götterdämmerung is uniformly excellent – but it is the Hagen of Simon Wilding who dominates it. I have often bemoaned a true bass singing the role of Hagen in recent productions I have seen or heard of this opera (such as last years LPO performance with Vladimir Jurowski when the more baritonal Alfred Dohmen sang the role – magnificent though he turned out to be). Wilding – if not always ink-black of tone – was often mesmerising and never more so than in a superb ‘Hagen’s Watch’ which had much power and malevolence to it; indeed, one could almost have called it something of a psychodrama so compelling was this singer’s acting. The sense of threat is never far away in this Hagen – whether it be in his semi-strangulation of Gunther or his near-molestation of Gutrune earlier on as he advises her to marry. His slaying of Alberich (a sonorous Oliver Gibbs) was downright vicious, even sociopathic (pulverised by the fire extinguisher). Agile and sinister, crouched on a column he pounced like an unsuspecting puma with murderous villainy. The voice projected magnificently; the notes all there, the diction supremely spot on. I found his gaze disconcerting, if I’m honest – something you’d never experience in an opera house, but which in York Hall, and in this boxing ring, draws you in in a way no other production of Götterdämmerung ever has.

Peter Furlong’s voice is of the heldentenor kind – and his Siegfried lasted the course with little difficulty. Top and bottom of the register are even of tone, although I would think twice about finding this Siegfried appealing: there could sometimes be a disconnect between appearance and the drama. Casual doesn’t even begin to do this track suited, mirror-sneakered hero justice. Was he convincing? I think so. There was a snarling arrogance in Furlong’s scene with the Rhinemaidens when he initially refused to give them the Ring and yet there was much beauty in his act 3 duet with Brünnhilde – and Hagen’s murder of Siegfried was compellingly done (also evincing genuine horror from Gunther). Andrew Mayor’s Gunther was a nice contrast with Siegfried for once (not all singers of the role are). He made more of the part than one usually expects from Gunther, too: exuding confidence, and the oath of the blood brotherhood scene with Siegfried was convincingly (and bloodily) done (indeed, much of act 2 was). Justine Viani’s Gutrune, perhaps a tad un-Wagnerian for me, had all of the role’s irritation and unsophisticated simplicity implicit in her singing. She found complete gullibility in her love for Siegfried; equally, she found it second nature to finally yield to Brünnhilde.

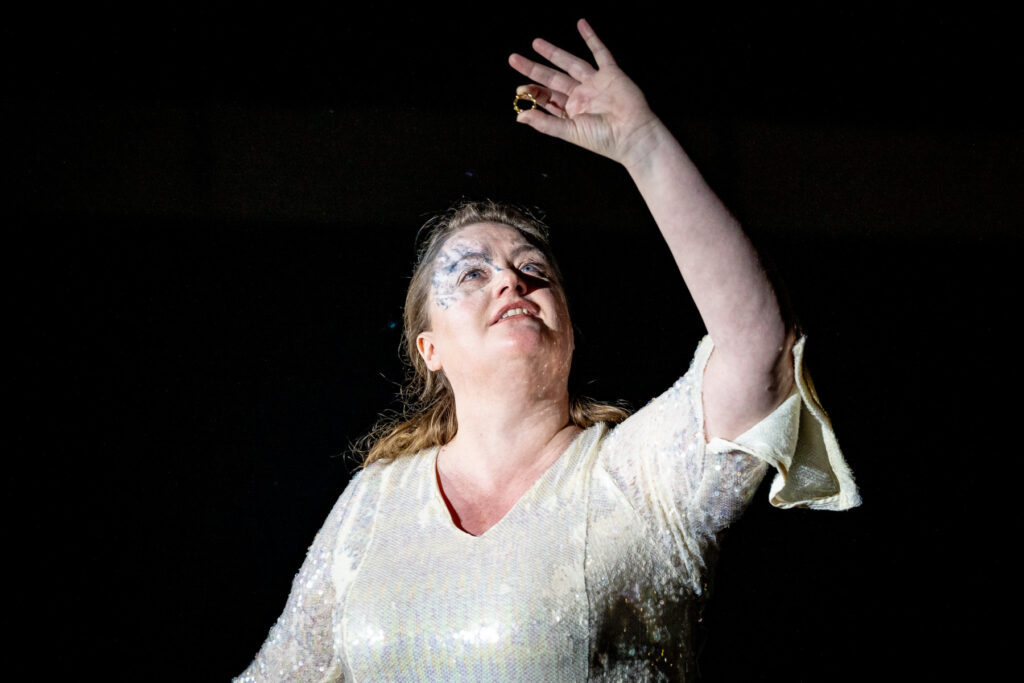

Catharine Woodward’s Brünnhilde was often superb – her voice a tremendous instrument of consummate power and beauty, a not inconsiderable virtue for this role in this particular Ring opera. Her horror at finding her impenetrable Rock broken – not by Siegfried but by Gunther – was a moment of brilliance, the voice spellbinding; but so, too, was she in act 2 in her scene with Wilding’s Hagen. It is as much the impact of her stage presence which works in her favour as it is her rich tone, one reason her indefatigable singing of the Immolation Scene was such a moment of triumph here. There was no sense of tiredness; no scooping of notes, no over-reliance on heavy vibrato – and top notes were effortlessly sung. As powerful a final scene as I have heard in recent performances of Götterdämmerung.

Elsewhere, there were hardly any weak links. The three Norns (Ingeborg Novrup Børch, Mae Heydorn and Jillian Finnamore) had been fabulously deep and velvety. The Rhinemaidens (Heydorn, Finnamore and Elizabeth Findon) were equally compelling. The vassals and Members of the London Gay Men’s Chorus – just a little too indistinct, perhaps – were dynamic in the Gibichung scenes, if not as volatile or impassioned in their singing as some I have heard in other performances.

I had wondered if the reduced orchestration would work in this of all the Ring operas and it largely did. Even in the big, purely orchestral parts – such as Siegfried’s Funeral Music – the playing was big enough for York Hall (although an added organ certainly gave volume and ballast to what might have been a smaller string sound, especially from a lack of bass or cellos). Largely the playing was fine, but by act 3 the orchestra were clearly struggling with intonation (horns awry, for example) and some of the violins were under strain. Ben Woodward conducted an extremely fluid account that never hung fire.

Caroline Staunton’s Götterdämmerung is a considerable success if we look at it through contemporary eyes. As Michael Downe’s alludes to in his booklet essay, her Ring coincidentally takes place in interesting times: Ukraine, Israel/Gaza and the ascendancy of a new presidency in the United States and, since the booklet notes were written, in recent weeks the upending of a postwar world order: at no time in almost 80 years have we perhaps lived in a time that is more politically unsettled than it is today, more turbulent and more uncertain. This Götterdämmerung felt fresh and modern because we could – or we should – have been able to relate to its contemporary look, to the stripping down of myth in it and the construction of a reality which makes it something touchable. In that, I think it succeeds.

Marc Bridle

Götterdämmerung

Words and music by Richard Wagner

Cast and production staff

Catharine Woodward – Brünnhilde; Peter Furlong – Siegfried; Simon Wilding – Hagen; Andrew Mayor – Gunther; Justine Viani – Gutrune; Catherine Backhouse – Waltraute; Oliver Gibbs – Alberich; Jillian Finnamore – Woglinde/Third Norn; Elizabeth Findon – Wellgunde; Mae Heydorn/Second Norn – Flosshilde; Ingeborg Novrup Børch – First Norn; Members of London Gay Men’s Chorus; Members of Regents Opera Upper Voices Chorus – Vassals

Caroline Staunton – Director; Isabella van Braeckel – Designer; Patrick Malmström – Lighting Design; Orchestra of Regents Opera; Ben Woodward, conductor.

Regents Opera, York Hall, London, 2 March 2025

Top image: The Rhinemaidens

Photos: © Steve Gregson