Here’s a welcome treat from the radio vaults in Dresden: the first (and only) recording of one of Johann Adolf Hasse’s most important and most demanding operas. Fortunately, the performance – recorded in concert in 1997 – is quite fine, ably demonstrating the work’s many strengths.

In mid-eighteenth-century Dresden, the reigning monarchs, August the Strong and then his son Friedrich Augustus II (electors of Saxony and kings of Poland), brought some of the best singers and composers in Europe to provide the music for the court chapel and for the magnificent court-run opera house. J. S. Bach, writing to his employers in (Protestant) Leipzig, pointed out how much better supported the musical establishment was in (Catholic-ruled) Dresden. One can gain a quick sense of what caused Bach such envy by looking at a marvelously informative and richly illustrated book by Robert and Traute Marshall: Exploring the World of J. S. Bach: A Traveler’s Guide. A 17-page chapter treats Dresden’s musical life, Bach’s seven or more visits to the city, and the major buildings there that Bach played in or may well have seen, learned about, or visited.

One of the main results of the Dresden monarchs’ passion for music and ostentatious display was a string of operas by Johann Adolf Hasse. The first of the Hasse operas for Dresden is today one of his best known: Cleofide (1731), written in part to show off the prodigious gifts of the court’s leading new star performer, Faustina Bordoni. This remarkable, fiery singer had just left London, after a remarkable tenure as one of Handel’s leading sopranos at the Royal Academy of Music in London. (She and Hasse had married in 1730. Her vocal and histrionic gifts are documented in Suzanne Aspden’s book Rival Sirens: Performance and Identity on Handel’s Operatic Stage.) In 1986, Cleofide received a stupendously fluent studio recording under William Christie, featuring such noted singers as sopranos Emma Kirkby and Agnès Mellon and countertenors Derek Lee Ragin, Dominique Visse, and Randall Wong. (Reviews by Charles Parsons, American Record Guide, November/December 2011, and – writing about an excerpt disc – John Barker, May/June 2009.)

Attilio Regolo (1750) marks yet another noteworthy moment in Hasse’s career at Dresden. He was the first composer to set this Metastasio libretto and therefore made no changes in it, such as substitute arias. Metastasio sent him some suggestions that are often cited today and help us understand opera seria generally.

The plot centers around the Roman consul Marcus Attilius Regulus, who, as history reports, was taken captive by the Carthaginians and then brought to Rome to sue for peace and for an exchange of prisoners. Regulus instead urged his compatriots to reject the offer. He returned to Carthage, where he was murdered in a gruesome fashion. The opera tells this tale most effectively, working into it also more freely imagined material, notably Regolo’s relationship to his two grown children, Attilia and Publio, Attilia’s love for Licinio (Roman tribune), and Publio’s for the Carthaginian gentlewoman (now slave) Barce. (The “o” names are all the Italian equivalents of the Latin “us”: Regulus, Publius, Licinius.)

The arias are studded with florid passages, and the score contains numerous colorful moments for oboes and horns (though only one aria with a concertante instrument – a flute). There are three long and extremely effective accompanied recitatives, i.e., ones in which the basso continuo is augmented by a string orchestra – or, in one case, strings plus oboes – playing rapid figurations, sudden stabs, long-held chords, and so on to emphasize the meaning of the sung words. Most strikingly, the final solo number is not an aria but the third of these accompanied recitatives, as Regolo self-sacrificingly departs for Carthage and certain death. The work ends with a farewell chorus for the principled leader. This closing number is sung here by the assembled soloists, as was quite possibly done at the time.

The performance is less consistent than the one heard on the Cleofide recording, ranging from stupefyingly wonderful to the (merely) very fine. A lot of this comes down to the basic difference between a studio recording – in which multiple takes are possible – and, as here, the recording of a single public performance.

Two of the best singers are the sopranos: Sibylla Rubens (though her infallibly lovely tone, full of quick, narrow vibrato, may strike some listeners as too much like that of a young woman – she is playing Regolo’s grown son Publio) and, as Barce, Carmen Fuggiss, a marvelously fleet and bright soprano who is very prominent in Germany but nearly unknown here. Mezzo Martina Borst (as Attilia) sounds thick early on, but has warmed up wonderfully by evening’s end: her final aria is one of the highlights of the whole recording. Bass Markus Volle is capable but not special in any way. One would have no inkling from this recording that he would be singing major Wagner roles at the Met two decades later!

Tenor Markus Schäfer produces a constant stream of beautiful tone, never blaring, though his florid singing and trill are a touch sluggish. Randall Wong is, as always, astonishing: a true male soprano, in admirable control of the coloratura, and very word-aware at the same time. Countertenor Axel Köhler is skillful in florid work. Unfortunately, his alto-pitched voice cannot encompass the lowest notes of the role. Sometimes he barely emits them; other times he resorts to his everyday (non-falsetto) voice, which makes them pop out unduly.

Indeed, several of the singers are sorely tested by the low notes in their arias. (Wong integrates his few non-falsetto low notes into the musical line better than does fellow countertenor Köhler.) I wonder if the singers were chosen for their ability to handle not just the written notes but the many higher ones that have been added (or that they themselves volunteered to add). Least appropriate, from the historical evidence, are the full-voiced (unwritten) high tonic notes at the ends of many arias, a present-day custom (whether in 1997 or 2025) that I suspect is simply a transference back into the Baroque of habits that are more appropriate to Donizetti and Verdi operas (and perhaps not always there, either).

The insistence on adding high notes thus reveals here a little-mentioned disadvantage: namely that a singer gets chosen who cannot do justice to arias’ lower notes. Castrati did not sing in falsetto but in their own normal vocal range: the same range in which they conversed or shouted. They thus must have commanded full-voiced low notes, and the same would have been the case with any women, tenors, and basses in the cast. I would rather hear a singer who can handle all the written notes of the aria – including low-lying passages, which often demand to be rendered with special force. But the performers are hardly unique in this respect: Conrad L. Osborne has demonstrated, and explained, “the disappearing low end” in vocal training nowadays, in his important (if oddly structured) book Opera as Opera: The State of the Art.

On the far bigger plus side of the ledger, the singers and continuo players here all handle the recitatives expertly, with clear awareness of meaning and syntax, and with much flexibility of tempo. It helps that the recitatives tend to lie near the middle of the respective singer’s range.

The conductor Frieder Brenius is extremely capable, as is the Dresden early-instrument ensemble. Though this is a recording of a concert performance (not an edited compilation from two or three performances), there is next to none of the disheveled ensemble that can sometimes arise in such situations. The varied tempi chosen by the conductor help hold the listener’s interest, and the faster numbers add excitement. Sometimes a number goes a little too fast, preventing the singer from articulating the florid passages clearly. In a studio situation, the tempo would probably have been moderated a bit to allow for greater note-perfection.

The recorded sound is clear, though the level seems to crank up for the recitatives, making us more aware of room noise. Fortunately, the audience is attentive and rarely coughs. The sound editors have retained long applause, lasting twenty seconds or more, after some arias (though other arias have none after them, for whatever reason). Excellent booklet essays, in German and (good!) English. The libretto is given only in Italian and German.

In short, a generally pleasing and occasionally treasurable recording, and the only one available. (Alessandro Scarlatti’s Marco Attilio Regolo, 1719, is based on a different libretto, which picks up where this one ends.) Hasse, and these performers, held my attention for nearly three hours, without any staging, facial expressions, or bodily gestures to help convey the drama. Indeed, during the recitatives I was often able to imagine the debates and confrontations as if I were watching a video.

It is surely time for more Hasse operas to get staged and then released on DVD. John Barker (American Record Guide, July/August 2016) was quite taken with the recent CD and DVD releases of Hasse’s Artaserse, in a performance from the 2012 Valle d’Itria Festival: “Hasse gave all of these roles some dauntingly virtuosic music, and this excellent cast brings it all off admirably.”

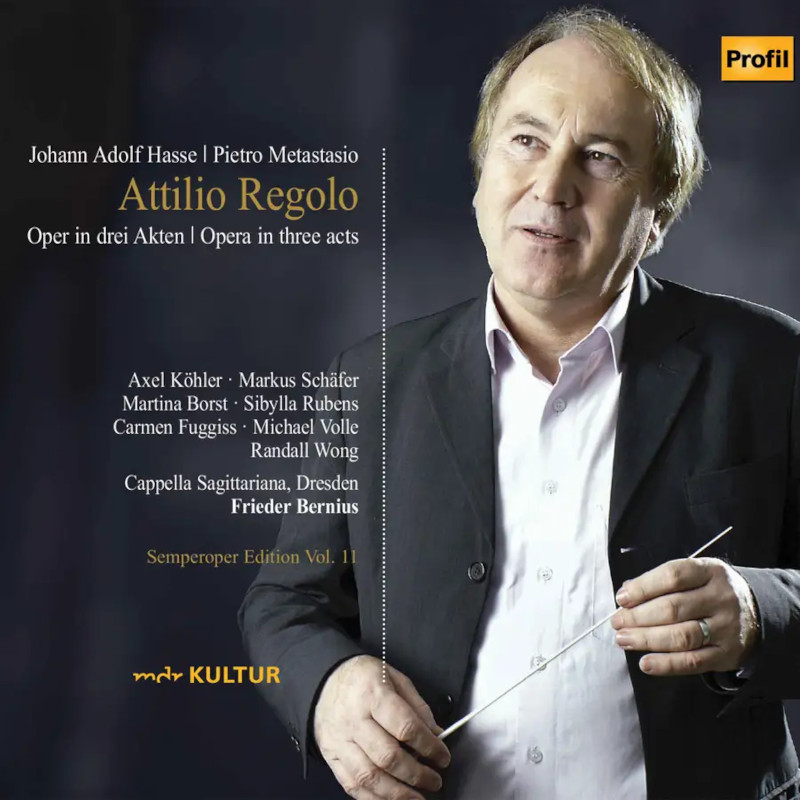

Bernius’s Attilio Regolo recording is vol. 11 of the Semperoper Edition, a CD series put out by the Dresden State Opera, the Central German Radio (MDR Figaro), and the German Radio Archive (DRA), under the aegis of the renowned tenor Peter Schreier. Vol. 5 of the series is Rudolf Kempe’s 1951 recording of Weber’s Der Freischütz (notable mainly, critics report, for the vivid personification of Kaspar by Kurt Böhme; Desmond Arthur, in American Record Guide, November/December 2000, stresses that the performance has a genuine theatrical feel to it).

Bernius made pathbreaking revivals – in Dresden and Stuttgart – of many other Baroque operas by Hasse, Jommelli, and their contemporaries. Do similar high-quality recordings of any of these survive in the German radio station vaults? If so, I vote for their being transferred to CD immediately.

Ralph P. Locke

Attilio Regolo

Opera seria by Johann Adolph Hasse

Libretto by Pietro Metastasio

Carmen Fuggiss (Barce), Sibylla Rubens (Publio), Martina Borst (Attilia), Randall Wong (Amilcare), Axel Köhler (Regolo), Markus Schäfer (Manlio), Michael Volle (Licinio).

Capella Sagittariana Dresden, conducted by Frieder Bernius.

Semperoper Edition Volume 11

Hanssler Profil PH07035 [3 CDs] 163 minutes.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music and Senior Editor of the Eastman Studies in Music book series (University of Rochester Press), which has published over 200 titles over the past thirty years. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, The Boston Musical Intelligencer, and Classical Voice North America (the journal of the Music Critics Association of North America). His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and is included here,

Top image: Departure of Attilio Regolo for Carthage (Preparatory sketch) by Vincenzo Camuccini (1824) [Source: WikiArt]