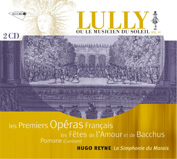

Jean-Baptiste Lully: Les Fetes de l’Amour et de Bacchus

Robert Cambert : Pomone

Hugo Reyne, La Simphonie du Marais

Accord 476 2437 [2 CDs]

Born in Florence, Jean-Baptiste Lully (1632-1687) came to France in 1646 as an Italian tutor to Louis XIV’s cousin Anne-Marie-Louise d’Orléans. Thanks to her, Lully became acquainted with French music, and got to study with several eminent musicians in Paris. In early 1653, he was asked to play several roles in the spectacular Royal Ballet of the Night. His performances caught the eye of King Louis XIV, who immediately appointed the young musician to the post of “Instrumental Music Composer.” Soon, Lully became Louis XIV’s favorite musician — he was appointed to the post of “Master of Music of the Royal Family” in 1662 — and the most important composer in France. Today, Lully is known primarily as the first major composer of French opera. (Unfortunately, he is also remembered for the way he died. In January 1687, Lully stabbed his foot with a cane that he used to beat time, and he succumbed to infections that resulted from this injury.)

Over the past seven years, Hugo Reyne and La Simphonie du Marais have been recording Lully’s works for Accord, a highly-regarded classical music label in France. This review considers the sixth installment in this series, and it contains premiere recordings of two of the earliest works in the history of French opera. The earlier composition is Pomone by librettist Pierre Perrin (1630-75) and composer Robert Cambert (c. 1628-77). In this five-act opera, Vertumne, the god of autumn, tries to woo Pomone, the goddess of fruits, by disguising himself as Pluto, Bacchus, and Pomone’s nurse Beroe. In the end, Vertumne wins Pomone’s hand and the work concludes with their wedding. The opera opened to critical acclaim in March 1671, and ran for 146 performances over a period of about seven months. Despite this initial success, the sole remaining source of Pomone contains only the first forty pages of the opera. It cuts off in the middle of the second act.

This release was recorded live in November 2003, and it contains every note of the extant score, which is just over half an hour of music. Throughout, La Simphonie du Marais offers subtly inflected and energetic playing. Outside of occasional ensemble and intonation problems, the singers, especially countertenor Renaud Tripathi, make fine contributions. My main reservations have to do with the work itself. Cambert’s music is certainly fluent and pleasant, but it does not contain much variety or character. Having read about this piece in various articles over the years, I am glad that I now have the opportunity to hear it. That said, I don’t think I will be returning to it very often.

The second work on this two-CD set is Lully’s Les fetes de l’Amour et de Bacchus (The Festivities of Cupid and Bacchus). A pastiche opera in three acts, this work — which consists largely of music from Lully’s comedies-ballets — was hastily compiled by Lully and his librettist Philippe Quinault (1635-88) shortly after the composer acquired a royal monopoly to form the Académie Royale de Musique in 1672. Featuring an unusually large cast that includes 15 singing roles, two choruses, two instrumental ensembles, 32 dancing characters, and 11 supernatural characters, Les fetes is at once a celebration of Louis XIV’s reign and of idyllic love. Full of elaborate sets, spectacular stage effects and elegant dance sequences, this opera was not only an enormous success during its opening run, but was also revived five times between 1689 and 1738.

This is a highly recommended recording. All the performers execute French Baroque music and its ornamentations with ease and conviction. Françoise Masset and Isabelle Desrochers are especially convincing; they possess fine voices, and sing with energy and intelligence in their multiple roles. La Simphonie du Marais plays with great finesse, flexibility and color (listen to the wonderful effects in the Airs of the Magicians in Act 2). At the same time, Lully’s music is always inventive, varied, and full of character. My one quibble is the chorus, which is peculiarly balanced on several occasions. Given the otherwise excellent quality of this recording, one might have to conclude that this was the inevitable result of recording a staged performance. Given the historical importance of these two works, one has to wonder why they were not released on DVD.

Eric Hung

Westminster Choir College of Rider University