![David Leventhal [Photo by Ken Friedman]](http://www.operatoday.com/Mark%20Morris1_David%20Leventhal%20in%20L%27Allegro%2C%20il%20Penseroso%20ed%20il%20Moderato.Photo%20by%20Ken%20Friedman.png)

19 Apr 2010

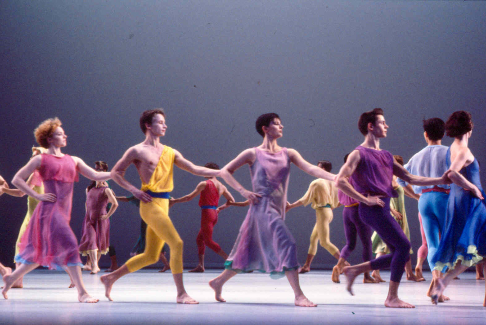

Mark Morris Dance Group: L’Allegro, il Penseroso ed il Moderato

‘Each action will derive new grace

From order, measure, time and place;’ (Milton, Il

Penseroso)

English Touring Opera are delighted to announce a season of lyric monodramas to tour nationally from October to December. The season features music for solo singer and piano by Argento, Britten, Tippett and Shostakovich with a bold and inventive approach to making opera during social distancing.

This tenth of ten Live from London concerts was in fact a recorded live performance from California. It was no less enjoyable for that, and it was also uplifting to learn that this wasn’t in fact the ‘last’ LfL event that we will be able to enjoy, courtesy of VOCES8 and their fellow vocal ensembles (more below …).

Ever since Wigmore Hall announced their superb series of autumn concerts, all streamed live and available free of charge, I’d been looking forward to this song recital by Ian Bostridge and Imogen Cooper.

The Sixteen continues its exploration of Henry Purcell’s Welcome Songs for Charles II. As with Robert King’s pioneering Purcell series begun over thirty years ago for Hyperion, Harry Christophers is recording two Welcome Songs per disc.

Although Stile Antico’s programme article for their Live from London recital introduced their selection from the many treasures of the English Renaissance in the context of the theological debates and upheavals of the Tudor and Elizabethan years, their performance was more evocative of private chamber music than of public liturgy.

In February this year, Albanian soprano Ermonela Jaho made a highly lauded debut recital at Wigmore Hall - a concert which both celebrated Opera Rara’s 50th anniversary and honoured the career of the Italian soprano Rosina Storchio (1872-1945), the star of verismo who created the title roles in Leoncavallo’s La bohème and Zazà, Mascagni’s Lodoletta and Puccini’s Madama Butterfly.

Evidently, face masks don’t stifle appreciative “Bravo!”s. And, reducing audience numbers doesn’t lower the volume of such acclamations. For, the audience at Wigmore Hall gave soprano Elizabeth Llewellyn and pianist Simon Lepper a greatly deserved warm reception and hearty response following this lunchtime recital of late-Romantic song.

Collapsology. Or, perhaps we should use the French word ‘Collapsologie’ because this is a transdisciplinary idea pretty much advocated by a series of French theorists - and apparently, mostly French theorists. It in essence focuses on the imminent collapse of modern society and all its layers - a series of escalating crises on a global scale: environmental, economic, geopolitical, governmental; the list is extensive.

For this week’s Live from London vocal recital we moved from the home of VOCES8, St Anne and St Agnes in the City of London, to Kings Place, where The Sixteen - who have been associate artists at the venue for some time - presented a programme of music and words bound together by the theme of ‘reflection’.

'Such is your divine Disposation that both you excellently understand, and royally entertaine the Exercise of Musicke.’

Amongst an avalanche of new Mahler recordings appearing at the moment (Das Lied von der Erde seems to be the most favoured, with three) this 1991 Mahler Second from the 2nd Kassel MahlerFest is one of the more interesting releases.

‘And there was war in heaven: Michael and his angels fought against the dragon; and the dragon fought and his angels, And prevailed not; neither was their place found any more in heaven … that old serpent … Satan, which deceiveth the whole world: he was cast out into the earth, and his angels were cast out with him.’

If there is one myth, it seems believed by some people today, that probably needs shattering it is that post-war recordings or performances of Wagner operas were always of exceptional quality. This 1949 Hamburg Tristan und Isolde is one of those recordings - though quite who is to blame for its many problems takes quite some unearthing.

There was never any doubt that the fifth of the twelve Met Stars Live in Concert broadcasts was going to be a palpably intense and vivid event, as well as a musically stunning and theatrically enervating experience.

‘Love’ was the theme for this Live from London performance by Apollo5. Given the complexity and diversity of that human emotion, and Apollo5’s reputation for versatility and diverse repertoire, ranging from Renaissance choral music to jazz, from contemporary classical works to popular song, it was no surprise that their programme spanned 500 years and several musical styles.

The Academy of St Martin in the Fields have titled their autumn series of eight concerts - which are taking place at 5pm and 7.30pm on two Saturdays each month at their home venue in Trafalgar Square, and being filmed for streaming the following Thursday - ‘re:connect’.

The London Symphony Orchestra opened their Autumn 2020 season with a homage to Oliver Knussen, who died at the age of 66 in July 2018. The programme traced a national musical lineage through the twentieth century, from Britten to Knussen, on to Mark-Anthony Turnage, and entwining the LSO and Rattle too.

With the Live from London digital vocal festival entering the second half of the series, the festival’s host, VOCES8, returned to their home at St Annes and St Agnes in the City of London to present a sequence of ‘Choral Dances’ - vocal music inspired by dance, embracing diverse genres from the Renaissance madrigal to swing jazz.

Just a few unison string wriggles from the opening of Mozart’s overture to Le nozze di Figaro are enough to make any opera-lover perch on the edge of their seat, in excited anticipation of the drama in music to come, so there could be no other curtain-raiser for this Gala Concert at the Royal Opera House, the latest instalment from ‘their House’ to ‘our houses’.

"Before the ending of the day, creator of all things, we pray that, with your accustomed mercy, you may watch over us."

![David Leventhal [Photo by Ken Friedman]](http://www.operatoday.com/Mark%20Morris1_David%20Leventhal%20in%20L%27Allegro%2C%20il%20Penseroso%20ed%20il%20Moderato.Photo%20by%20Ken%20Friedman.png)

‘Each action will derive new grace

From order, measure, time and place;’ (Milton, Il

Penseroso)

What fitter words to describe Mark Morris’s L’Allegro, Il Penseroso ed Il Moderato which, 22 years since it first amazed audiences at the Théâtre de la Monnaie in Brussels, still has the power to incite wonder, astonishment and joy.

Handel’s pastoral ode is a musical reflection upon Milton’s philosophical meditations on the gregarious, the introspective and the balanced modes of living. His librettist, Charles Jennens, (best known as the librettist of The Messiah), selected and assembled Milton’s poems sequentially, and added the text for Il Moderato; Morris re-arranges once again, moving continually but naturally between contrasting states, the frolicking lightness of L’Allegro tempered by the brooding melancholy and pensiveness of Il Penseroso; and he adds two movements from Handel’s Concerto Grosso Op.6 No.1 to serve as an overture.

Music’s power to express emotional states, or affekts, and to produce ethical responses in the listener, was an essential thesis of the seventeenth-century artistic and spiritual imagination, and one which continued to be upheld by eighteenth-century composers of opera seria. Here, Morris seems almost literally to lift the notes from the page as his dancers physically embody the rhythms, textures and figures of the musical score; his forms present a stunning visualisation of the way music can initiate or allay particular passions and sentiments. And, in so doing, Morris reveals his own, oft-remarked, innate musicality and, more especially, a profound appreciation of the architecture and ethos of baroque musical forms. Rigorous, mathematical choreographic structures are interlaced with ornamented mannerisms and deviant whirls; gestural cliché sits happily alongside surprising idiosyncrasy.

Morris is ably supported by his designers. The warm lighting (James F. Ingalls) effortlessly matches the modulations from light to shade, from clarity to opacity, of Morris’s sequence; it is complemented by Adrianne Lobel’s simple but purposeful conception of the literal and philosophical spaces suggested by text and score - the dancing arena now foreshortened, now extended, almost imperceptibly, by an airy array of descending drops and gauzes. Christine Van Loon’s costumes gladly conjure the pastoral simplicity of classical nymphs and shepherds, the muted pastels of ‘Part the First’ giving way to more vibrant tones in the latter half.

William Blake’s nineteenth-century illustrations of Milton’s poems are cited as a visual influence; but also evoked are the stained-glass windows of a gothic cathedral, panes of many and contrasting colours through which the light reverberates illuminating tales in rich tapestries — such windows as Milton himself described in Il Penseroso, ‘Storied panes richly dight’.

Indeed, the intersection of the vertical and horizontal in Morris’s forms, and in Lobel’s shifting panels and flats, does suggest the meeting-point of heaven and earth, of spirit and flesh, as expressed in the perpendicular architecture of the seventeenth century. Most fittingly then, Morris combines narrative with abstraction for in so doing he combines qualities inherent in seventeenth-century verse, with its integration of the human and heavenly, with those of eighteenth-century music, with its preference for metrical regularity, abstract universality and conceptual clarity.

To focus overly on such weighty matters is, however, to overlook that in this collection of more than 30 dances, gravity is equalled and occasionally challenged by Morris’s trademark wit and irony. In an hilarious hunting scene, three leashed dogs pursue fleeing foxes, pausing momentarily to urinate under a tree; even in such wry fun there is beauty, as the changing landscape is simulated by dancers evoking gnarled branches which form and re-form almost imperceptibly before our eyes. Elsewhere seriousness is alleviated with irreverence, as Morris makes playful reference to the formal salutations and farewells of baroque custom and dance. Throughout there is effortless fluidity between change and stasis, speed and stillness.

The work comprises a rich assortment of solos and ensemble pieces, including a startlingly complicated ‘canon’ for three pairs of dancers — momentarily revealing the technical and choreographic complexity which underpins behind the deceptive simplicity of so much of Morris’s seemingly natural, ‘human’ movement. But ultimately this is a company piece, the group extended to 24 dancers; it is not surprising therefore that it is in the choral scenes where Morris’s invention and confidence is most powerfully evident. Most noteworthy are the final scenes in each Part: in the closing scene, to the celebratory accompaniment of vibrant trumpet fanfares, the 24 dancers form streams of colour, streaking and darting across the stage, conjuring startling pace, energy and joie de vivre — ‘These delights if thou canst give/ Mirth with thee I mean to live’.

The four singers, sopranos Sarah-Jane Brandon and Elizabeth Watts, tenor Mark Padmore and bass Andrew Foster-Williams, all projected the narrative superbly, blending convincingly with the stage drama, enhancing and receding as appropriate. Foster-Williams, in particular, delivered his airs with buoyancy and brightness. Jane Glover skilfully conducted the alert, energised members of the English National Opera Orchestra, bringing freshness and translucence to Handel’s score; the woodwind were especially impressive, exquisitely evoking the pastoral milieu, as when first a lark, and then a whole flock of birds, intricately twist and tumble in fantastic flight, their aspiring arcs symbolised by a scintillating soaring soprano. The New London Chorus were crisp and clear throughout.

The ‘imperfect, labouring’ bodies noted by Joan Acocella in her 1994 critical biography - and which once exemplified Morris’ preference for dancers who whose physicality captured the mortality and genuine ‘flesh-and-blood’ of the human form — were no longer so dominant, replaced by a sweet litheness of form and truly eloquent tenderness. Yet, Morris’s pastoral vision is not an ethereal or idealised landscape but an earthy dominion where the rich diversity of the human spirit is rejoiced. Capturing all the elements which have characterised Morris’s career — beauty and realism, levity and gravity, formal rigour and quirky invention — it remains utterly captivating and uplifting. It is, in the words of Milton himself, ‘linckèd sweetnes long drawn out. (L’Allegro)

Claire Seymour