![Daniela Dessi as Fedora, Act II [Photo courtesy of Teatro San Carlo]](http://www.operatoday.com/Fedora_Genoa1.png)

31 Mar 2015

Fedora in Genoa

It is not an everyday opera. It is an opera that illuminates a larger verismo history.

English Touring Opera are delighted to announce a season of lyric monodramas to tour nationally from October to December. The season features music for solo singer and piano by Argento, Britten, Tippett and Shostakovich with a bold and inventive approach to making opera during social distancing.

This tenth of ten Live from London concerts was in fact a recorded live performance from California. It was no less enjoyable for that, and it was also uplifting to learn that this wasn’t in fact the ‘last’ LfL event that we will be able to enjoy, courtesy of VOCES8 and their fellow vocal ensembles (more below …).

Ever since Wigmore Hall announced their superb series of autumn concerts, all streamed live and available free of charge, I’d been looking forward to this song recital by Ian Bostridge and Imogen Cooper.

Although Stile Antico’s programme article for their Live from London recital introduced their selection from the many treasures of the English Renaissance in the context of the theological debates and upheavals of the Tudor and Elizabethan years, their performance was more evocative of private chamber music than of public liturgy.

Evidently, face masks don’t stifle appreciative “Bravo!”s. And, reducing audience numbers doesn’t lower the volume of such acclamations. For, the audience at Wigmore Hall gave soprano Elizabeth Llewellyn and pianist Simon Lepper a greatly deserved warm reception and hearty response following this lunchtime recital of late-Romantic song.

For this week’s Live from London vocal recital we moved from the home of VOCES8, St Anne and St Agnes in the City of London, to Kings Place, where The Sixteen - who have been associate artists at the venue for some time - presented a programme of music and words bound together by the theme of ‘reflection’.

'Such is your divine Disposation that both you excellently understand, and royally entertaine the Exercise of Musicke.’

‘And there was war in heaven: Michael and his angels fought against the dragon; and the dragon fought and his angels, And prevailed not; neither was their place found any more in heaven … that old serpent … Satan, which deceiveth the whole world: he was cast out into the earth, and his angels were cast out with him.’

There was never any doubt that the fifth of the twelve Met Stars Live in Concert broadcasts was going to be a palpably intense and vivid event, as well as a musically stunning and theatrically enervating experience.

‘Love’ was the theme for this Live from London performance by Apollo5. Given the complexity and diversity of that human emotion, and Apollo5’s reputation for versatility and diverse repertoire, ranging from Renaissance choral music to jazz, from contemporary classical works to popular song, it was no surprise that their programme spanned 500 years and several musical styles.

The Academy of St Martin in the Fields have titled their autumn series of eight concerts - which are taking place at 5pm and 7.30pm on two Saturdays each month at their home venue in Trafalgar Square, and being filmed for streaming the following Thursday - ‘re:connect’.

The London Symphony Orchestra opened their Autumn 2020 season with a homage to Oliver Knussen, who died at the age of 66 in July 2018. The programme traced a national musical lineage through the twentieth century, from Britten to Knussen, on to Mark-Anthony Turnage, and entwining the LSO and Rattle too.

With the Live from London digital vocal festival entering the second half of the series, the festival’s host, VOCES8, returned to their home at St Annes and St Agnes in the City of London to present a sequence of ‘Choral Dances’ - vocal music inspired by dance, embracing diverse genres from the Renaissance madrigal to swing jazz.

Just a few unison string wriggles from the opening of Mozart’s overture to Le nozze di Figaro are enough to make any opera-lover perch on the edge of their seat, in excited anticipation of the drama in music to come, so there could be no other curtain-raiser for this Gala Concert at the Royal Opera House, the latest instalment from ‘their House’ to ‘our houses’.

"Before the ending of the day, creator of all things, we pray that, with your accustomed mercy, you may watch over us."

The doors at The Metropolitan Opera will not open to live audiences until 2021 at the earliest, and the likelihood of normal operatic life resuming in cities around the world looks but a distant dream at present. But, while we may not be invited from our homes into the opera house for some time yet, with its free daily screenings of past productions and its pay-per-view Met Stars Live in Concert series, the Met continues to bring opera into our homes.

Music-making at this year’s Grange Festival Opera may have fallen silent in June and July, but the country house and extensive grounds of The Grange provided an ideal setting for a weekend of twelve specially conceived ‘promenade’ performances encompassing music and dance.

There’s a “slide of harmony” and “all the bones leave your body at that moment and you collapse to the floor, it’s so extraordinary.”

“Music for a while, shall all your cares beguile.”

The hum of bees rising from myriad scented blooms; gentle strains of birdsong; the cheerful chatter of picnickers beside a still lake; decorous thwacks of leather on willow; song and music floating through the warm evening air.

![Daniela Dessi as Fedora, Act II [Photo courtesy of Teatro San Carlo]](http://www.operatoday.com/Fedora_Genoa1.png)

It is not an everyday opera. It is an opera that illuminates a larger verismo history.

If the operas of Giacomo Puccini are the standard bearers for operatic verismo, the stories of Giovanni Verga hold that place in literature. And there was the Casa Sonzogno [an Italian opera publishing house destroyed by a WWII bomb] that sponsored the famous 1888 competition in which Pietro Mascagni’s Cavalleria Rusticana (libretto on a story by Verga) took first place and became the emblematic moment of verismo.

A now forgotten opera by Umberto Giordano, Mala Vita (An Unhappy Life) took sixth place (out of 73 entries) in that competition. Mala Vita is the grizzly tale of a tuberculosis stricken prostitute and was in fact performed in 1890. Note that Puccini’s La boheme premiered in 1896.

Meanwhile in those same years Giordano saw the famed French tragedienne Sarah Bernhardt as Fédora and Puccini saw la Bernhardt as La Tosca, eponymous plays by Victorien Sardou. This facile playwright gave the public what it wanted — intense moments for dramatic outbursts against a colorful historical backdrop, with no demand that the public wade through motivations or contexts.

The operas Fedora (1898) and Tosca (1900) are very similar pieces. Both are three brief acts, both are about a powerful female in a politically volatile climate, both end in suicide. But where Puccini lyrically expands the personalities of his protagonists into rich, post romantic music, Giordano stays very close to the action making his story an intense, fast moving single action. Lyric moments are brief and fiery, generally less than a couple of minutes, the music looking forward to the more direct, minimalist tendencies of twentieth century music drama.

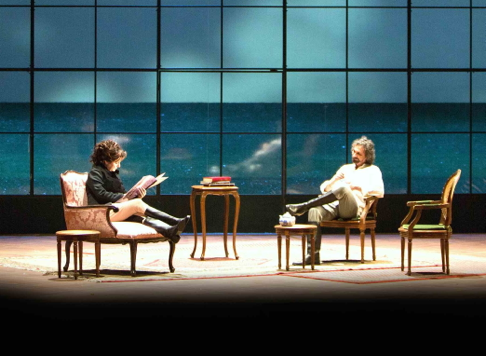

The new production of Fedora in Genoa attempts to bring historical depth to the Sardou play. Stage director Rosetta Cucchi and her set designer Tiziano Santi created a huge, full stage window looking upstage onto an imaginary plain where actions went well beyond the direct, let us say brutal happenings taking place downstage — Fedora’s mortally wounded fiance is brought on stage to die (Act 1), Fedora falls in love with the murderer and betrays him to the police (Act II), Fedora regrets this and kills herself (Act III).

The contexts for these acts played out in this imaginary space were visually splendid if rather confusing. There were battle fields that made us think of the of the 1916 revolution far more than remind us of the the specific context of Sardou’s play — the 1881 assassination of Alexander II. This impression was reinforced by a tableau portrait by costumed supernumeraries of the Czar’s family that made us think of the 1918 murders of the Romanov family. [See lead photo.]

To complicate these contexts the whole opera was played as a flashback — a duplicate Loris (as the by now very aged assassin of Fedora’s fiance) sat on the stage apron for the entire opera (including intermissions) only to walk into the imaginary plain in the final moments of the opera for a brief encounter/recognition of a young goatherd, perhaps the youngest son of the assassinated Ivan the Terrible. Or what?

Daniela Dessi as Fedora, Fabio Armiliato as Loris, Act III

Daniela Dessi as Fedora, Fabio Armiliato as Loris, Act III

Of course none of this really mattered because Giordano’s opera is about the immediate passions of a rich Russian aristocrat, the widow Fedora. Fedora was sung by 56 year-old diva Daniela Dessi. Loris, the assassin of her fiancé and a suspected nihilist, was sung by 59 year-old Fabio Armiliato (both ages determined by birth dates found on the internet). These two formidable artists are partners in real life. Both were in good voice, but voices no longer capable of carving Giordano’s unique vocal exclamations in easy tones, relying instead large, uncolored wooden sounds. It was obvious that both artists knew well and once embodied the vocalism and the musicality of the style, and that they were working hard and honestly to achieve it again. The result was compromised.

Fedora’s friend Olga was enacted by Russian soubrette Daria Kovalenko, ably creating the intended overbearing presence of such a Slavic personality. Pianist (in real life) Siriio Restani, the Carlo Felice house pianist, had his moment in the spotlight giving the Act II solo concert against which Fedora and Loris declare their love in a precious scene that would find itself perfectly at home in the shallow sensualism and sensationalsim of Italian decadentismo, a parallel style to gritty verismo.

Daniela Dessi as Fedora, male supporting cast

Daniela Dessi as Fedora, male supporting cast

The myriad of smaller roles were executed with typical Italian panache.

The greater impact of the evening was lost by a late start for the brief first act, explained somewhat by an announcement about some casting problem, then there was an overly long first intermission. After the brief second act there was a very extended intermission (one can assume there was some backstage drama, left unexplained). The orchestra players became impatient and began stamping their feet, and finally we were given the brief third act. The far less-than-sold-out house gave la Dessi a huge ovation.

The pit at the Teatro Carlo Felice does not offer a great presence to an orchestra. None the less it was obvious that we were in fine musical hands. Young conductor Valerio Galli, already a verismo specialist, made the most of Giordano’s sophisticated score over this too long evening.

Michael Milenski

Cast and production information:

Fedora: Daniela Dessì; Loris: Fabio Armiliato; De Siriex: Alfonso Antoniozzi; Olga: Daria Kovalenko; Dimitri: Margherita Rotondi; Desiré: Manuel Pierattelli; Il Barone Rouvel: Alessandro Fantoni; Cirillo: Luigi Roni; Boroff: Claudio Ottino; Gretch: Roberto Maietta; Lorek: Davide Mura; Nicola: Matteo Armanino; Sergio: Pasquale Graziano; Michele: Roberto Conti; Boleslao Lazinski: Sirio Restani. Chorus and Orchestra of Teatro Carlo Felice. Conductor: Valerio Galli; Metteur en scène: Rosetta Cucchi; Set Design: Tiziano Santi; Costumes: Claudia Pernigotti; Lighting: Luciano Novelli. Teatro Carlo Felice, Genoa, March 25, 2015.