Recently in Reviews

English Touring Opera are delighted to announce a season of lyric monodramas to tour nationally from October to December. The season features music for solo singer and piano by Argento, Britten, Tippett and Shostakovich with a bold and inventive approach to making opera during social distancing.

This tenth of ten Live from London concerts was in fact a recorded live performance from California. It was no less enjoyable for that, and it was also uplifting to learn that this wasn’t in fact the ‘last’ LfL event that we will be able to enjoy, courtesy of VOCES8 and their fellow vocal ensembles (more below …).

Ever since Wigmore Hall announced their superb series of autumn concerts, all streamed live and available free of charge, I’d been looking forward to this song recital by Ian Bostridge and Imogen Cooper.

The Sixteen continues its exploration of Henry Purcell’s Welcome Songs for Charles II. As with Robert King’s pioneering Purcell series begun over thirty years ago for Hyperion, Harry Christophers is recording two Welcome Songs per disc.

Although Stile Antico’s programme article for their Live from London recital introduced their selection from the many treasures of the English Renaissance in the context of the theological debates and upheavals of the Tudor and Elizabethan years, their performance was more evocative of private chamber music than of public liturgy.

In February this year, Albanian soprano Ermonela Jaho made a highly lauded debut recital at Wigmore Hall - a concert which both celebrated Opera Rara’s 50th anniversary and honoured the career of the Italian soprano Rosina Storchio (1872-1945), the star of verismo who created the title roles in Leoncavallo’s La bohème and Zazà, Mascagni’s Lodoletta and Puccini’s Madama Butterfly.

Evidently, face masks don’t stifle appreciative “Bravo!”s. And, reducing audience numbers doesn’t lower the volume of such acclamations. For, the audience at Wigmore Hall gave soprano Elizabeth Llewellyn and pianist Simon Lepper a greatly deserved warm reception and hearty response following this lunchtime recital of late-Romantic song.

Collapsology. Or, perhaps we should use the French word ‘Collapsologie’ because this is a transdisciplinary idea pretty much advocated by a series of French theorists - and apparently, mostly French theorists. It in essence focuses on the imminent collapse of modern society and all its layers - a series of escalating crises on a global scale: environmental, economic, geopolitical, governmental; the list is extensive.

For this week’s Live from London vocal recital we moved from the home of VOCES8, St Anne and St Agnes in the City of London, to Kings Place, where The Sixteen - who have been associate artists at the venue for some time - presented a programme of music and words bound together by the theme of ‘reflection’.

'Such is your divine Disposation that both you excellently understand, and royally entertaine the Exercise of Musicke.’

Amongst an avalanche of new Mahler recordings appearing at the moment (Das Lied von der Erde seems to be the most favoured, with three) this 1991 Mahler Second from the 2nd Kassel MahlerFest is one of the more interesting releases.

‘And there was war in heaven: Michael and his angels fought against the dragon; and the dragon fought and his angels, And prevailed not; neither was their place found any more in heaven … that old serpent … Satan, which deceiveth the whole world: he was cast out into the earth, and his angels were cast out with him.’

If there is one myth, it seems believed by some people today, that probably needs shattering it is that post-war recordings or performances of Wagner operas were always of exceptional quality. This 1949 Hamburg Tristan und Isolde is one of those recordings - though quite who is to blame for its many problems takes quite some unearthing.

There was never any doubt that the fifth of the twelve Met Stars Live in Concert broadcasts was going to be a palpably intense and vivid event, as well as a musically stunning and theatrically enervating experience.

‘Love’ was the theme for this Live from London performance by Apollo5. Given the complexity and diversity of that human emotion, and Apollo5’s reputation for versatility and diverse repertoire, ranging from Renaissance choral music to jazz, from contemporary classical works to popular song, it was no surprise that their programme spanned 500 years and several musical styles.

The Academy of St Martin in the Fields have titled their autumn series of eight concerts - which are taking place at 5pm and 7.30pm on two Saturdays each month at their home venue in Trafalgar Square, and being filmed for streaming the following Thursday - ‘re:connect’.

The London Symphony Orchestra opened their Autumn 2020 season with a homage to Oliver Knussen, who died at the age of 66 in July 2018. The programme traced a national musical lineage through the twentieth century, from Britten to Knussen, on to Mark-Anthony Turnage, and entwining the LSO and Rattle too.

With the Live from London digital vocal festival entering the second half of the series, the festival’s host, VOCES8, returned to their home at St Annes and St Agnes in the City of London to present a sequence of ‘Choral Dances’ - vocal music inspired by dance, embracing diverse genres from the Renaissance madrigal to swing jazz.

Just a few unison string wriggles from the opening of Mozart’s overture to Le nozze di Figaro are enough to make any opera-lover perch on the edge of their seat, in excited anticipation of the drama in music to come, so there could be no other curtain-raiser for this Gala Concert at the Royal Opera House, the latest instalment from ‘their House’ to ‘our houses’.

"Before the ending of the day, creator of all things, we pray that, with your accustomed mercy, you may watch over us."

Reviews

10 Apr 2016

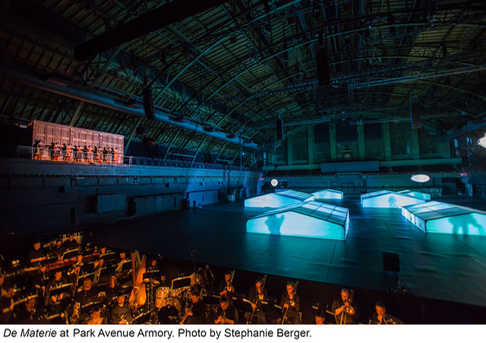

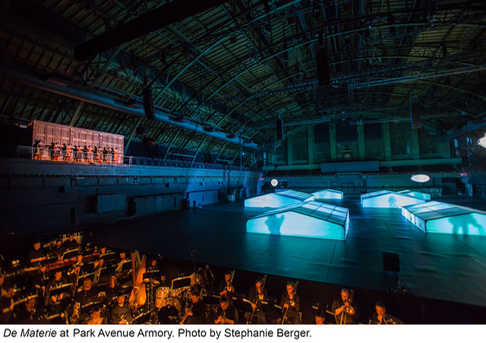

Andriessen's De Materie at the Park Avenue Armory

"The large measure of formalism which forms the basis of De Materie does not in itself offer any guarantee that the work will be beautiful," says Dutch composer Louis Andriessen of his four-movement opera.

The opera, composed in 1985-1988, received its North American stage première in March 2016 at the Park Avenue Armory. Indeed, there were moments of the music that were stereotypically unbeautiful, particularly during the hammered clangor of the first movement. This opera does not make for "easy listening". But these moments, challenging the ear and mind of the listener, are beautiful, at least in the Marxist sense of the word, illustrating the rhythms and realism of human existence as they jolt us out of futile reveries and delusions of myth. This production of De Materie, directed brilliantly by Heiner Goebbels, was surprising in many respects (and, yes, I'll get to the sheep). Yet it was Andriessen's music, performed in all its miraculous starkness by the International Contemporary Ensemble, that elevated the performance to what will surely be remembered as one of the top cultural events of the year.

The first movement, intended as an evocation of the Dutch seventeenth-century ship-building industry, opens with the same brutally loud, metallic chord repeated 144 times in the brass and percussion. In De Materie Andriessen turns minimalism on its head in the same vein of his 1975 Workers' Union, which is scored for "any loud-sounding group of instruments"; repetition and process music get melted down into something more earthy and dissonant. The sounds were made even more elemental and unexpected by their sources' location; the musicians were partially obscured from the audience but must have been steered with precision by conductor Peter Rundel. The brash bangs and clangs contrasted bitingly with the human voices interspersed as Chorwerk Ruhr began singing from a balcony. These sounds were juxtaposed with the elegant visuals of Florence von Gerkan's costumes and Klaus Grünberg's stage and lighting design: glowing tents arranged like a checkerboard along the enormous black stage of the Park Avenue Armory; likewise glowing blimps floated languidly overhead. Occasionally the text of the vocals would appear in wavering font along the side of a tent or blimp. However, this wasn't a narrative meant to be followed linearly but rather glimpsed in momentary bursts, through the cacophony and confusion.

Throughout the second, third, and fourth movements, sharply defined musical moods were likewise paired with abstract, sleek visuals and Goebbels' continually startling direction. During the second movement, a stunning 25-minute long aria was sung by soprano Evgeniya Sotnikova in the role of 13th-century mystic poetess Hadewych. As she sang, her face frequently obscured by her dark robe, a procession of rectangular-costumed figures bowed and posed and held their bodies in contorted positions, scattered throughout a checkerboard of pews. Occasionally their positions would change; at one point a burbling bassoon interrupted the legato vocals and strings. The next movement—a scherzo to the second movement's adagio—featured a team of dancers choreographed by Florian Bilbao, including boogie-woogie soloists Gauthier Dedieu and Niklas Taffner. Jazzy, pointillistic music was here paired with a Mondrianesque acrobat show, visually centered around a pendulum and the color blocks (red, yellow, blue, black, white) associated with the early twentieth-century visual art movement De Stijl. The frenzied dancing continued; the musicians' platform rotated across the stage; and finally, 100 Pennsylvanian sheep made their way onto the stage.

The fourth movement was a bit anti-climactic; I had heard about the sheep but couldn't discern their purpose, other than to make the final 25 minutes of the opera somewhat awkward and smelly. Audience members coughed and buried their noses in their sleeves; I don't envy whoever's job it was to clear the stage of sheep excrement in between performances. As the sheep followed each other around the stage, occasionally eliciting a humorous "baa!", the final portrait began. Dancer Catherine Milliken read out Marie Curie's regretful reminiscences, first accompanied by simple, repeated chords from the percussion and then by silence. She continued reading aloud, both from Curie's diaries and from her Nobel Prize acceptance speech, as a group of silent men filed into the performance space, in a visual echo of the sheep. Eventually, the percussion crescendoed on a recurring metallic tone; the opera, quite suddenly, was over. I thought surely I had missed something. What were the sheep there for—as a further commentary on the state of humanity? Another tile in the mosaic of Dutch culture and history? The entire fourth movement felt contrived, not to mention confusing. And yet, it seemed so far from reality as to negatively illustrate reality, bringing about what Goebbels laid out as his goal in the program note: "art, and theater too, should not imitate reality nor represent it, but it should insist on the difference to empirical reality." Andriessen's opera—and Goebbels's production of it—is extraordinary in its illumination of the chasm between art and reality, the instability of matter and of spirit, and the beauty of ugliness.

Rebecca Lentjes