![Alpha-Classics: Alpha 273 [CD]](http://www.operatoday.com/Poschner_Alpha_front.png)

16 Apr 2018

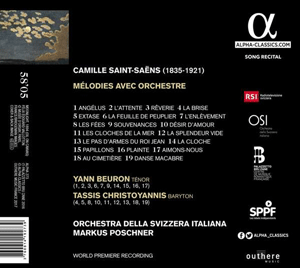

Camille Saint-Saens: Mélodies avec orchestra

Saint-Saëns Mélodies avec orchestra with Yann Beuron and Tassis Christoyannis with the Orchestra della Svizzera Italiana conducted by Markus Poschner.

The Sixteen continues its exploration of Henry Purcell’s Welcome Songs for Charles II. As with Robert King’s pioneering Purcell series begun over thirty years ago for Hyperion, Harry Christophers is recording two Welcome Songs per disc.

In February this year, Albanian soprano Ermonela Jaho made a highly lauded debut recital at Wigmore Hall - a concert which both celebrated Opera Rara’s 50th anniversary and honoured the career of the Italian soprano Rosina Storchio (1872-1945), the star of verismo who created the title roles in Leoncavallo’s La bohème and Zazà, Mascagni’s Lodoletta and Puccini’s Madama Butterfly.

Collapsology. Or, perhaps we should use the French word ‘Collapsologie’ because this is a transdisciplinary idea pretty much advocated by a series of French theorists - and apparently, mostly French theorists. It in essence focuses on the imminent collapse of modern society and all its layers - a series of escalating crises on a global scale: environmental, economic, geopolitical, governmental; the list is extensive.

Amongst an avalanche of new Mahler recordings appearing at the moment (Das Lied von der Erde seems to be the most favoured, with three) this 1991 Mahler Second from the 2nd Kassel MahlerFest is one of the more interesting releases.

If there is one myth, it seems believed by some people today, that probably needs shattering it is that post-war recordings or performances of Wagner operas were always of exceptional quality. This 1949 Hamburg Tristan und Isolde is one of those recordings - though quite who is to blame for its many problems takes quite some unearthing.

The voices of six women composers are celebrated by baritone Jeremy Huw Williams and soprano Yunah Lee on this characteristically ambitious and valuable release by Lontano Records Ltd (Lorelt).

As Paul Spicer, conductor of the Royal Birmingham Conservatoire Chamber Choir, observes, the worship of the Blessed Virgin Mary is as ‘old as Christianity itself’, and programmes devoted to settings of texts which venerate the Virgin Mary are commonplace.

Ethel Smyth’s last large-scale work, written in 1930 by the then 72-year-old composer who was increasingly afflicted and depressed by her worsening deafness, was The Prison – a ‘symphony’ for soprano and bass-baritone soloists, chorus and orchestra.

‘Hamilton Harty is Irish to the core, but he is not a musical nationalist.’

‘After silence, that which comes closest to expressing the inexpressible is music.’ Aldous Huxley’s words have inspired VOCES8’s new disc, After Silence, a ‘double album in four chapters’ which marks the ensemble’s 15th anniversary.

A song-cycle is a narrative, a journey, not necessarily literal or linear, but one which carries performer and listener through time and across an emotional terrain. Through complement and contrast, poetry and music crystallise diverse sentiments and somehow cohere variability into an aesthetic unity.

One of the nicest things about being lucky enough to enjoy opera, music and theatre, week in week out, in London’s fringe theatres, music conservatoires, and international concert halls and opera houses, is the opportunity to encounter striking performances by young talented musicians and then watch with pleasure as they fulfil those sparks of promise.

“It’s forbidden, and where’s the art in that?”

Dublin-born John F. Larchet (1884-1967) might well be described as the father of post-Independence Irish music, given the immense influenced that he had upon Irish musical life during the first half of the 20th century - as a composer, musician, administrator and teacher.

The English Civil War is raging. The daughter of a Puritan aristocrat has fallen in love with the son of a Royalist supporter of the House of Stuart. Will love triumph over political expediency and religious dogma?

Beethoven Symphony no 9 (the Choral Symphony) in D minor, Op. 125, and the Choral Fantasy in C minor, Op. 80 with soloist Kristian Bezuidenhout, Pablo Heras-Casado conducting the Freiburger Barockorchester, new from Harmonia Mundi.

A Louise Brooks look-a-like, in bobbed black wig and floor-sweeping leather trench-coat, cheeks purple-rouged and eyes shadowed in black, Barbara Hannigan issues taut gestures which elicit fire-cracker punch from the Mahler Chamber Orchestra.

‘Signor Piatti in a fantasia on themes from Beatrice di Tenda had also his triumph. Difficulties, declared to be insuperable, were vanquished by him with consummate skill and precision. He certainly is amazing, his tone magnificent, and his style excellent. His resources appear to be inexhaustible; and altogether for variety, it is the greatest specimen of violoncello playing that has been heard in this country.’

Baritone Roderick Williams seems to have been a pretty constant ‘companion’, on my laptop screen and through my stereo speakers, during the past few ‘lock-down’ months.

Melodramas can be a difficult genre for composers. Before Richard Strauss’s Enoch Arden the concept of the melodrama was its compact size – Weber’s Wolf’s Glen scene in Der Freischütz, Georg Benda’s Ariadne auf Naxos and Medea or even Leonore’s grave scene in Beethoven’s Fidelio.

![Alpha-Classics: Alpha 273 [CD]](http://www.operatoday.com/Poschner_Alpha_front.png)

Saint-Saëns Mélodies avec orchestra with Yann Beuron and Tassis Christoyannis with the Orchestra della Svizzera Italiana conducted by Markus Poschner.

Though the songs for voice and piano have previously been recorded, this is the world premiere recording of the full orchestral versions, taken from a performance in Lugano in 2016 sponsored by Palazzetto Bru-Zane, champions in the promotion of French repertoire. In this landmark issue, distributed by Alpha classics, nineteen of the twenty-five orchestral songs in the composer's catalogue are included.

Saint-Saëns was only thirteen years old when he wrote L'Enlèvement, in 1848, first for piano and voice, orchestrating it very shortly afterwards. Aimons-nous was completed seventy years later, two years before the composer's death. Though Saint-Saëns’ reputation has been based on his larger works, he had a lifelong commitment to song. This is particularly significant given the dominance of Grand Opéra and symphonic works in mid-19th century France. Berlioz's Les nuits d'été was initially composed for voice and piano, the orchestrations only completed in 1856. Concert performances tended towards programmes of operatic arias or works for piano.

By orchestrating his songs, Saint-Saëns was making an artistic statement. In 1876, he wrote "The Lied with orchestra is a social necessity. If such things were available, people would not always be singing operatic arias in concerts, which often make a pitiful effect in those surroundings". As Sébastien Troester writes in his notes, "incongruous accents and faulty ceasuras and enjambments" could occur in popular works by composers whose native language was not French. Thus Saint-Saëns created orchestral song as art song as serious concert music, a synthesis of voice and symphony, building on the riches of French poetry. Orchestral form also allows for exotic colour and sensuality, making use, as Troester writes "of ancient modes, of ostinato rhythms that create a sensation of languor, of vocal melismas", distinctive and very Belle Époque.

The performances here are superb, the epitome of idiomatic style. Despite its richness, the beauty of Saint-Saëns music lies in its purity. The ornamenations exist to amplify ideas and structure. Poschner and the orchestra keep, the colours clear. "Hollywood excess" is not the way to go Elegance lies in articulation. Beuron and Chritoyannis phrase and shape so that the words can be heard clearly, without exaggeration, but with natural, flowing flair.

Angélus, to a poem by Pierre Aguétant (1890-1940) begins with the tolling of a bell, followed by shimmering strings. "Les clochers, souverains du soir", sings the tenor Yann Beuron, pacing the line with the deliberation of medieval chant. In the monastery, the monks are singing Angelus, and outside, the shepherds hear the sound on the air as if the wings of God were rushing past. Similar frisson in the strings introduces L'attente (Victor Hugo) but here the pace is swift, barely able to contain excitement. "Climb, squirrel, up the oak.... eagle, rise from your eyrie!" In Rêverie (Hugo) phrases in each strophe are repeated, with slight variation, the orchestra echoing the vocal line, the effect as lovers entwined. Beuron's wonderful diction warms words tenderly: "Mon coeur, dont rien ne reste, L'amour ôté ! "

Extended orchestral colour pays off handsomely in songs like La Brise from Saint-Saëns' Mélodies Persanes op 26 (1870) to a text by Arrmand Renaud (1836-1895). Swaying string lines suggest exotic dance, against dance rhythms based on percussion and bells. A clarinet suggests "oriental" woodwinds. The vocal line (Tassis Christoyannis) equally agile, with long, curving phrases. Similar felicities in Extase (Hugo) where the text itself repeats and changes in intricate patterns. Woodwinds "mobile et tremblante" suggest the falling leaves in La feuille de peuplier (Mme Amable Tastu, 1795-1885). A lilting woodwind melody lifts L'Enlèvement (Hugo) raising the song to heights few composers aged only 13 could hope to achieve. Woodwinds again in Les Fées (Théodore de Banville 1821-1891) suggest the movement of swallows in flight, as the vocal line soars upwards. The vocal line (Beuron) in Souvenances (Ferdinand Lemaire 1832-1879) dips gracefully, garlanded by the orchestra.

Flutes and strings shimmer in Les cloches de la mer to a text by the composer himself, but a much darker, more dramatic mood emerges, the orchestra surging tutti, suggesting the depths of the ocean. La splendeur vide from Mélodies Persanes op 26. describes "un merveilleux palais" filled with jewels (vividly evoked by the orchestra), but the glory masks despair. "Plus je suis tombeau", sings Troyannis, his voice descending to near whisper. The full orchestra surges again, horns ablaze, in Le pas d'armes du roi Jean (Hugo) a long ballad where the singer (Troyannis) has to characterise the different figures in the poem, while marking the short, clipped phrases in the text.

More mock medievalism in La cloche (Hugo) where Beuron floats the last line "dans le ciel" so it dissolves into silence. This prepares us for the fluttering delicacy of Papillons (Renée de Léché) where a pair of flutes duet, darker winds and strings adding texture. The song ends abruptly : butterflies die. Thus Pliante (Tastu), (1918) with strong chords of dark portent. "Ô monde ! Ô vie ! Ô temps!". In contrast, though written in the same period, Aimons-nous (Banville) where lovers embrace, peacefully, in death. In Au cimetière again from Mélodies persanes the two groups of strings are plucked, then bowed, suggesting the beat of a pulse and sighs of breath. The mood is hushed, yet enraptured. To conclude, Danse macabre op 40 but with a difference. This was originally written for voice and piano in 1872, then revised for violin and orchestra. Here, voice, violin and orchestra come together. It's a treat ! Christoyannis sings "zig-a-zig-za-zig le mort en cadence". Violin and voice locked in sinister dance. Méfistofeles having a laugh. Truly "et vive la mort et l'egalité!"

Anne Ozorio