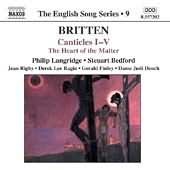

Benjamin Britten: Canticles I-V, The Heart of the Matter

Philip Langridge, tenor; Jean Rigby, alto; Derek Lee Ragin, countertenor; Gerald Finley, baritone; Dame Judi Dench, speaker; Steuart Bedford, piano; Osian Ellis, harp

Naxos 8.557202 [CD]

Benjamin Britten is usually thought of as a musical dramatist on a large, operatic scale, but the instinct (or perhaps the inner necessity) to capture psychological conflict in music burst through in his smaller musical forms as well. His five canticles (not to be confused with the church parables) mirror Britten’s artistic growth in his operas and other large-scale works from the late 1940s until shortly before his death.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines a “canticle” as “A song, properly a little song; a hymn” and secondarily as a hymn used on a recurring basis in church services. Britten didn’t draw upon the Scriptures for the texts of his canticles, which resemble cantatas more than church hymns in scale and structure, but an intense religious spirit pervades them all.

Canticle I, My Beloved Is Mine, sets a text by the early-seventeenth-century Royalist poet Francis Quarles for tenor (originally composed for Britten’s partner Peter Pears, of course) and piano. An interesting aspect of this canticle is the singer’s references to a male lover (“So I my best beloved’s am, So he is mine!” — these words taken from the Song of Solomon). It has been assumed that Britten was expressing his feelings for Pears (publicly in 1947!) through the piece, especially its lovely ending, with the singer confident of his place in his lover’s heart.

Britten biographer Humphrey Carpenter (who passed away recently) notes that Britten composed some of the canticles immediately after completion of an opera–in the case of Canticle I, Albert Herring — forming an epilogue to the opera. The first scene of Herring has text taken from the same chapter of the Bible as Quarles drew upon, and of course Albert’s sexual anxieties are relieved by the end of the opera, much as Britten’s seem to be here. I think these pieces should more correctly be called pendants (quoting the OED again: “An additional statement, consideration, etc., which completes or complements another”; a companion piece) to the operas that precede them.

Canticle II, Abraham and Isaac, for tenor, alto (premiered by Kathleen Ferrier), and piano, is probably the most familiar of the set, as Britten reused parts of it in his War Requiem. Britten drew upon the Chester Miracle Play version of the story and turns the confrontation between Abraham and God into a true operatic scena. God (sung in a high union by the tenor and alto) and man are far apart here — God in the key of E-flat, Abraham in the key of A — but by the end God and man are reconciled in a hushed Be-still-and know-that-I-am-God E-flat major. Carpenter suggests that Canticle II forms a companion piece to the recently completed Billy Budd, as Melville’s novella compares Vere’s feeling for Billy to Abraham’s for Isaac when he is commanded to sacrifice him.

Canticle III, Still Falls the Rain, sets a poem by Dame Edith Sitwell, “The Raids 1940. Night and Dawn,” for tenor, horn, and piano. The most overtly religious text among the five canticles, this piece, achingly beautiful in its anguish, followed closely upon the completion of The Turn of the Screw and uses a similar twelve-note theme and variation technique. Britten set this canticle into a larger-scale work for the 1956 Aldeburgh Festival that he called The Heart of the Matter. In this adaptation, recorded here for the first time in a revision by Pears after the composer’s death, Britten surrounds the canticle with readings from other Sitwell works (read here by Dame Judi Dench) and a sung prologue, song (“We Are the Darkness in the Heat of Day”), and sung epilogue. The additional musical numbers can’t be said to stand up against most of the songs in Britten’s oeuvre, but they are attractive in context here.

Canticle IV, The Journey of the Magi, breaks new ground in the canticles by using three voices: countertenor, tenor, and baritone, with piano. A setting of the T. S. Eliot poem, it echoes the themes of religious questioning in the previous two canticles as the wise men, years after their journey to Bethlehem, ponder the significance of what they had seen there. In this recording the exquisite Derek Lee Ragin sings the countertenor part; one can’t imagine a more perfectly realized performance. The magical ending, as the three voices weave aethereal harmonies, must be much like what Prospero heard as Ariel kept watch over his island.

In the fifth canticle, The Death of Saint Narcissus, Britten returned to Eliot, this time a very early work of his aesthetic period. Here again we have a pendant to a just completed opera, Death in Venice. Narcissus is a “dancer before God”; of course, dance plays an important structural role in Britten’s opera. Like Aschenbach, Narcissus is obsessed with beauty (namely, his own) and seeks out death. In this last of the canticles, Britten relies on harp accompaniment for the tenor, though it is more a harp commentary than an accompaniment.

Other recordings of the complete canticles precede this one, including one by Britten and Pears for Decca, one with Ian Bostridge (David Daniels singing Isaac in Canticle II) on Virgin Classics, and one with Anthony Rolfe Johnson (Michael Chance singing Isaac) on Hyperion. The new recording is notable on several counts, not least the elegant singing of Philip Langridge. The texts for the two Eliot poems aren’t included, but they are hardly needed in Canticle V, Langridge’s diction is so superb. Accompanists should never be slighted: Steuart Bedford and Osian Ellis (who premiered Canticle V) are first-rate partners, as are Dench, Ragin, alto Jean Rigby, and baritone Gerald Finley. This recording is the one to buy if you don’t already own a recording of the canticles (and one to buy even if you do): most of all for the superb performances, but also the performance of Canticle II with a female alto as Britten conceived it and the expanded setting of Canticle III.

David Anderson