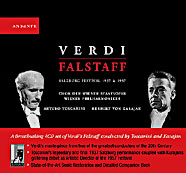

Giuseppe Verdi, Falstaff

Salzburg Festival 1937 & 1957

Andante AN3080 [4CDs]

Salzburg Festival, 9 August 1937

Mariano Stabile (baritone) – Sir John Falstaff

Virgilio Lazzari (bass) – Pistola

Augusta Oltrabella (soprano) – Nannetta

Angelica Cravcenco (mezzo-soprano) – Mrs. Quickly

Mita Vasari (mezzo-soprano) – Mrs. Meg Page

Franca Somigli (soprano) – Mrs. Alice Ford

Pietro Biasini (baritone) – Ford

Dino Borgioli (tenor) – Fenton

Alfredo Tedeschi (tenor) – Dr. Cajus

Giuseppe Nessi (tenor) – Bardolfo

Arturo Toscanini (conductor)

Chor der Wiener Staatsoper Wiener Philharmoniker

Salzburg Festival, 10 August 1957

Tito Gobbi (baritone) – Sir John Falstaff

Mario Petri (bass) – Pistola

Anna Moffo (soprano) – Nannetta

Giulietta Simionato (mezzo-soprano) – Mrs. Quickly

Anna Maria Canali (mezzo-soprano) – Mrs. Meg Page

Elisabeth Schwarzkopf (soprano) – Mrs. Alice Ford

Rolando Panerai (baritone) – Ford

Luigi Alva (tenor) – Fenton

Tomaso Spataro (tenor) – Dr. Cajus

Renato Ercolani (tenor) – Bardolfo

Herbert von Karajan (conductor)

Chor der Wiener Staatsoper Wiener Philharmoniker

This Andante release is a marvelous compilation of two recordings of Verdi’s Falstaff performed at the Salzburg festival, the first conducted by Arturo Toscanini in 1937, the second by Herbert Von Karajan in 1957. The juxtaposition and accompanying extensive program notes encourage the aficionado to compare, contrast and delight in the music through the lens of time. Falstaff was a favorite of the maestri and both took professional chances with it. Toscanini performed Falstaff during his first season at La Scala in 1898; Karajan perplexed his German-speaking audience by programming Falstaff in Aachen during his final season in 1941-2.

Karajan had plenty of access to Toscanini’s genius, working as the Salzburg Festival’s répétiteur during Toscanini’s tenure there between 1934 and 1937. Of a production of Falstaff with Mariano Stabile, Karajan recalled:

“To be sure, Toscanini had employed a stage director; but basically the essential conception came from him. The agreement between the music and the stage performance was something totally inconceivable to us. Instead of people standing pointlessly around, here everything had a purpose.”

Like Giulietta Masina and Fellini, Verdi viewed Toscanini as an artist who could bring to fruition his aesthetic. Toscanini played the cello in Verdi’s La Scala orchestra for the premiere of Otello, where Verdi asked him to play a passage more loudly at one rehearsal. But one of Toscanini’s earliest memories of Verdi was the composer advising the young boy to drink sugared water as a remedy for a pernicious cough. The maestro and composer embraced the Risorgimento, as fellow citizens of the Parma region, the belly of modern Italy, and Toscanini told his mother to get down on her knees after a performance of Otello and exclaim “Viva Verdi.”

Viva Verdi, Toscanini and Karajan. These recordings are terrific. But how to listen to them historically? Start with perusing a score, perhaps from the local library. Study the orchestration, the unusual uses of the piccolo, the sforzandi and elided numbers. Verdi leaves little room for breathing in this swash of opera. Sweeping diatonic melodies alternate with divisive rests and accents. Unlike Wagner, the story is not in the music, but in the singing. Verdi is a dramatist at heart, and the drama is in the vocal line. Aria and recitative are of equal importance here, like a favorite singing teacher’s melodic directives.

Listen to Karajan (1957), read the excellent notes that provide biographies for each singer and follow the libretto in the CD jacket. The opening is furious. Tito Gobbi’s performance combines the silly and the sexy. Falstaff is a bumbler dressed in a luscious baritone. Secure, forthright and convincing, Stabile’s voice is clear. The beguiling Elizabeth Schwarzkopf and Giulietta Simionato join him as the equally scheming women. These voices meld nicely and are suited as supporting roles to Gobbi’s star vehicle. Humor comes easily for all involved. Above all listen for Karajan’s impeccable performance. The voices are clear, rhythmically precise and the orchestra is synched with the fine performances. In general, Karajan takes the tempi faster, and time starts and stops faster than it does with Toscanini. Some critics of Falstaff claim that the climax happens too quickly, with Falstaff tossed from the balcony already at the end of Act II. Karajan remedies the problem with enthusiastic Act III merriment and a thrilling Finale “Everything in the World is a Joke.”

I would move to Toscanini’s Falstaff Finale, for in it we can hear his genius in a nutshell. Toscanini’s fugue is Bach and pastries, clear, metronomic and fast, frilly. Deliberate. Where Karajan takes time, Toscanini returns it. It is FAST. Even the interrupting soloists. The Finale is rigorous and virtuosic, in a way that the opera Falstaff is not. It ends in a breathtaking accelerando and we hear the audience clapping jubilantly. History moves in circles in these recordings and I suggest returning to Act I keeping in mind that Mariano Stabile sang the role close to 1,200 times!

If Toscanini is the voice of Verdi, then Stabile is that of Falstaff. It is as if the orchestra and voices are one, with quick shifts in tempo executed perfectly together under the maestro’s baton. Stabile’s voice is brash and exuberant. He too is accompanied by competent accomplices, Virgilio Lazzari’s Pistol and Giuseppe Nessi’s Bardolph. Toscanini’s performance is raw and edgy; however, the quality of the recording is not as good as that from 1957, with occasional scratches and difficulties hearing offstage singing. But still nothing detracts from the laundry-basket scene. Here in the midst of an onslaught of melodic and dramatic nuances, Toscanini masterfully holds the whole thing together, so that no note, no accent is left to flutter in the wind.

Take an afternoon and reacquaint yourself with these historic renditions of Falstaff.

Nora Beck

Lewis & Clark College