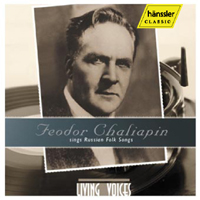

Feodor Chaliapin sings Russian folk songs

Living Voices Series

Hänssler Classic 945040 [CD]

This new release from Hänssler Classics presents an anthology of live and studio performances by the Russian bass Feodor Chaliapin (1873-1938), undoubtedly one of the greatest singers in recorded history. The title of the album, “Feodor Chaliapin sings Russian Folk Songs,” is somewhat misleading. Apart from traditional songs such as “Mashenka,” “Eh, Van’ka,” and “Down the Volga,” the recording includes arrangements of 19th-century popular songs such as “Dubinushka,” “Down the Peterskaya,” and the perennial Gypsy favorite “Black Eyes,” as well as a selection of salon romances, art songs, and ballads by Mikhail Glinka, Alexander Dargomïaut;zhsky, Anton Rubinstein, and Modest Musorgsky, among others. Most of the selections on the new CD have been previously released on various labels, with the possible exception of “Dubinushka,” which I have not been able to find among the recordings currently available. Hence, avid Chaliapin collectors should be aware that the Hänssler release offers little if anything new to them. Those music lovers still unacquainted with Chaliapin’s art, however, or those whose exposure to this singer has been limited to his opera recordings, would find this album a great insight into a spectacular voice and a unique artistic persona.

Feodor Chaliapin’s 45-year career has been tied for the most part to the operatic stage. Born near Kazan on the Volga river, he first joined an operatic troupe in Tiflis (now Tbilisi, Georgia), and later performed on various stages in St Petersburg. In 1896, the 24-year-old singer made a decision that would change his life and catapult him to stardom: he agreed to join the troupe of the Moscow Private Opera created, sponsored, and directed by art patron and railway tycoon Savva Mamontov (1841-1918). At this company, Chaliapin developed the classic roles of his repertoire, including Susanin (Glinka, Life for the Tsar), Mephistopheles (Gounod, Faust), the Miller (Dargomïaut;zhsky, Rusalka), Prince Galitsky (Borodin, Prince Igor), Nilakantha (Delibes, Lakmé), the Varangian Guest (Rimsky-Korsakov, Sadko), Dosifey (Musorgsky, Khovanshchina), and Boris (Musorgsky, Boris Godunov). The singer befriended a group of modernist painters associated with the company who revolutionized his ideas on costume, props, make-up, facial expression, and stage movement. He was also exposed to Mamontov’s own innovative vision of fusing opera and drama on stage — a vision that also influenced Konstantin Stanislavsky’s concept of method acting. By the time Chaliapin entered the stage of the Imperial Bolshoi Theater in Moscow only three years later, he was already a fully formed, unique creative artist that the world came to know during the remainder of his international career.

In Russia, meanwhile, Feodor Chaliapin’s reputation extended far beyond the walls of the opera houses in which he performed. He was known to people in the barracks and universities, factories and street markets – people of all walks of life, including those who had never in their lives attended an opera performance. During the revolutionary uprising of 1905-07, and later in the years following the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, Chaliapin — a rich dandy known to enjoy the wealth that came with his stardom — was seen performing charity concerts in front of thousands of people in factories and shipyards. He sang folk lyrical songs like “Eh, Van’ka” and “Mashenka,” traditional robber and Cossack ballads such as “Stenka Razin” and “The Legend of the Twelve Brigands,” and revolutionary songs, including the ever-popular “Dubinushka,” a frequent encore. A unique aspect of the singer’s approach to his material was a natural, almost nonchalant, conversational manner of performance, with his voice casually traveling the gamut between singing and ordinary speech. Even while performing art songs, Chaliapin’s sometimes controversial interpretations tend to stray away from the score to infuse the music with the unique dramatic power of his personality. Rare among classically trained singers, this approach proved particularly conducive to performing the folk and popular songs Chaliapin recorded throughout his career — a living tradition that thrives on improvisation and expressive freedom. A recording of Feodor Chaliapin singing this repertory is therefore a must in any opera lover’s collection.

Olga Haldey

University of Missouri-Columbia