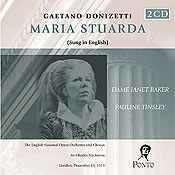

Gaetano Donizetti: Maria Stuarda (sung in English)

Dame Janet Baker (Mary Stuart); Pauline Tinsley (Queen Elizabeth I); Keith Erwen (Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester); Don Garrard (George Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury); Christian Du Plessis (Sir William Cecil); Audrey Gunn (Hannah Kennedy)

The English National Opera Orchestra and Chorus conducted by Sir Charles Mackerras

Live recording London, 13 December 1973

Ponto 1031 [2CDs]

One of the more interesting debates in arts politics in England last century centered on the language in which operas should be performed. While some staunchly favored opera in the original, others maintained that librettos should be translated into the vernacular. The latter side felt strongly that opera in English would nurture a national style of operatic presentation; a more chauvinistic argument suggested that if native composers heard opera in English, they would be more likely to attempt to set original English librettos (which, of course, would come from the pens of similarly inspired writers). Benjamin Britten and W.H. Auden’s Peter Grimes (1945) might be interpreted as representative of such a strategy. In addition, the mounting of vernacular performances also would inspire British performers (and discourage foreign singers who would be less likely to want to relearn a role in a new language). The debate eventually led to the division of operatic labor, with Covent Garden (soon to be renamed The Royal Opera) to perform works in their original languages and Sadler’s Wells (renamed the English National Opera after its move to the Coliseum, where it remains today) to produce works in translation. Thus, it was left up to audiences to decide which they preferred–or, better yet, to enjoy them both.

The Ponto label is presently in the process of issuing recordings of operas starring the great English mezzo Dame Janet Baker. The third in this series is her performance as Mary Stuart in Donizetti’s Maria Stuarda in the 1973 English National Opera production (other Baker recordings issued by Ponto include Handel’s Admetus in English and Gluck’s Alceste in French). This recording merits note for a variety of reasons. First, it serves as an example of the aims of the aestheticians who deemed opera in translation a necessity in mid-twentieth century England. As translations go–and some can be dead wrong–this libretto stays well within the meaning of Giuseppe Bardari’s original text. One might wish that the program booklet included the translator’s name, but perhaps it was unknown even to the Ponto producers. In addition to significance, the selected vocabulary also matches well with the melodic line; hence, instead of awkward patches of sounds one often hears in performances employing translated librettos (English or otherwise), the sung text flows well with the music.

In the context of the opera’s history, this recording also proves of interest. Donizetti composed the opera for Naples and specifically for one of his favorite sopranos, Giuseppina Ronzi De Begnis. The Bourbon censors, however, were always touchy about tales that suggested political coups or the death of a monarch, so the subject was rejected as written. Donizetti reworked the opera as Buondelmonte, which premiered at the San Carlo in 1834. Enter the legendary Maria Malibran, who wanted to perform the opera as it had been composed. Censors in Milan were no more enthusiastic about the tale than were their colleagues in Naples, but Malibran skirted their orders and sung the work without revision, resulting in a ban against the work. A heavily-censored score was employed for subsequent performances. Early twentieth-century performances, including the one on this recording, are based on revised versions of the score. Only in the late 1980s when Donizetti’s autograph manuscript was discovered in Sweden was the opera returned to its original two-act form, now published in the critical edition of the composer’s works.

This recording is a prime example of Baker’s artistry. Indeed, this version of the score, which Donizetti lowered for Malibran’s own mezzo voice, suits her perfectly. Baker’s ability to create dramatic portrayals is apparent as well, especially in scenes with Keith Erwen (Leicester) and especially in the final numbers of Act III such as “Death hovers near me, so take my pardon” (“D’un cor che muore reca il perdono” in the original). Soprano Pauline Tinsley, another classic of this golden age of the ENO, performs ably as Elizabeth, but her voice (perhaps as captured in this live recording) is often less brilliant and less skilled than Baker’s. Indeed, in “May the light of wisdom and justice” (“Ah! del ciel discenda un raggio”), she clings for dear life to the dangerously high penultimate note of the cadenza. Dramatically, however, she matches Baker in scenes in which the rival half-sisters (also rivals for Leicester’s affections) meet head on. Erwen has a pleasant and lyrical tone, but his interpretation is somewhat stereotypical of a bel canto tenor. Of even greater concern is a questionable sense of pitch; he tends to sit on the flat side of a pitch, a trait particularly noticeable in his duets with Baker and Tinsley, who to their credit fail to allow him to pull them down off the correct note. Credible interpretations are turned in by bass Don Garrard as Talbot, baritone Christian Du Plessis as Cecil, and mezzo Audrey Gunn as Hannah. Although all are not British, all are native English speakers (Garrard is Canadian and Plessis, South African); hence, all fit the image of the singers whom vernacular advocates were promoting.

The CD includes a list of the tracks and liner notes (by Andrew Palmer) but no printed libretto. Although the cast members carefully enunciate, in strettas like “My arrogant rival has long sought to rob me” (“Sul crin la rivale la man mi stendea”) the text simply is sung too quickly for comprehension. If issuing more of Baker’s (or anyone’s) performances in English is intended, this might be something Ponto could keep in mind.

Aside from the usual blemishes of a live recording – applause, coughs, singers’ footsteps as they trod the stage – this Maria Stuarda documents an important stage in the mature compositions of one of the dramatic masters of the Ottocento, an equally important part of the narrative of English opera in the twentieth century, and one of England’s greatest voices.

Denise Gallo