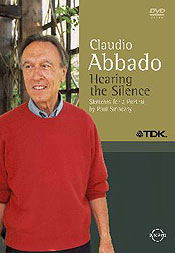

Claudio Abbado: Hearing the Silence — Sketches for a Portrait

Produced and directed by Paul Smaczny

TDK Euroarts 2053278 [DVD]

Five minutes into this DVD there has been a lot of talk on Abbado’s aura, his aristocratic reserve and the fact that he is a private thinker. With a deep sigh I was reminded of some of those dreadful documentaries on Arte (a German-French arts channel which I have on cable) that have promising titles and then soon lose themselves in a lot of philosophical treatises without any real content. And what was almost the last image of this documentary?: “In collaboration with Arte”

Subtitles like “hearing the silence” and “sketches” and not a portrait itself should have warned me and they keep their promises: lots and lots of vague high-minded talk with some hidden nuggets. After ten minutes into this experience we get some footage of 1968 in an interview with Marcel Prawy, the recently deceased grand old man of opera in Austria. Prawy asks some simple but really interesting questions and so we learn that Abbado as a young music student in Vienna was not allowed to attend rehearsals with the great conductors on the roster. His solution was simple: with his good bass-baritone he became a temporary member of the chorus and saw the great men in action. End of the historical footage. But an interviewer really interested in Abbado’s art would have asked what he learned, if indeed he learned anything, by watching Karajan and Walter. And another inevitable question would have been: how did his own singing experiences influence his behaviour towards his singers in his many operatic performances? Nothing of this at all. The only moment we see Abbado conducting an opera is during a less typical performance of Elektra and there is no comment at all on the problems of that difficult relationship between stage and pit, of Abbado’s vision on “Das Regietheater.”

Of course there are a lot of interviews with some of his players and here too it is strange to note that nobody offers hard facts on Abbado’s stick technique, his downbeat or other important signs of music making. We learn that everybody calls him Claudio and not maestro, that he is very democratic, charismatic, etc. but what does that tell us? Indeed, the only really interesting details are given by Abbado himself for 30 seconds and strangely enough by his friend and actor Bruno Ganz who has studied Abbado’s gestures during a concert. In exchange Ganz may expand on every question of life and death, recite German poems of Hölderlin (admired by Abbado) so that the director can show some landscapes and tell us there were problems with composer Luigi Nono. What kind of problems? That’s not for us to know. Ganz has almost as much to tell as Abbado himself and we should not forget that the actor is “hot” as he played (not too well in my opinion) the title role in “Der Untergang,” the movie about Hitler’s last days.

There is a lot of footage on Abbado’s concerts and there at last we can see for ourselves how he leads with his eyes and the “pa, pa, pa” sounds he makes. But it is not clear why this or that piece is chosen. No one ever asks the conductor which kind of composers he prefers or why he conducts this and not that. It comes as a kind of surprise in this philosophical entertainment that such worldly themes as his illness — he was diagnosed with cancer 4 years ago — pop up though he now distinctly looks better than a few years ago when, with superhuman strength, he continued conducting and one feared he would not finish some concerts. We also learn that he left the Berliner Symphoniker of his own accord in 2002, though it is a lifetime post. Of course everybody deeply regrets his decision and there is no dissenting voice to tell some of the less savoury stories. The orchestra deeply loved its maestro but it loved something more: money. For one or another reason (a saturated market; Abbado’s simplicity and humility compared with his predecessor’s incessant marketing of himself) Abbado’s records didn’t sell well: often only a few thousand copies were sold worldwide. At one time, the Berliner and Abbado were even relegated to accompanying the love couple’s (Alagna-Gheorgiu) Verdi duets. That didn’t sit well with an orchestra that remembered too well the rich pickings on the record market during Karajan’s era. The grumbling and his illness were reasons enough for Abbado to keep the honour of resigning to himself. All in all, this DVD is a missed chance.

Jan Neckers