Mariella Devia may not be the flavor-of-the-month in “au courant” operatic circles; she may not

be giving come-hither looks in the current round of air-brushed Rolex ads; nor may recording

companies be promoting her in hyper-drive as the next “diva du jour” (read: meal ticket).

Nevertheless, in La Scala’s new and highly effective “Maria Stuarda,” Signora Devia scored her

considerable artistic triumph the old-fashioned way, free of hype and extra-musical baggage, by

simply showing up and singing the living hell out of the titular queen, like any truly great star

surely should.

I first heard this wonderful artist. . .well, a number of years ago, and I remembered hers to be a

full, flexible, accomplished lyric voice with good thrust. Not a fussy, artsy interpreter, she made

fine effect with heartfelt, well-studied vocalizing, sound technique, and simplicity of gesture.

The good news is that, lo, these many years later, although time has darkened the instrument a

bit, this accomplished soprano is still singing superlatively well. And she still looks petite and

lovely, to boot.

Ms. Devia has all the requisite assets at her command to make a most persuasive case for our

heroine. She negotiates even the trickiest coloratura with skill and accuracy, and imbues it with

dramatic meaning. She scores every single time with spot-on, thrilling notes “in alt.” Indeed at

opera’s end, she sang what seemed like a “q” above high “z” sounding as fresh as at the start,

beginning the note at moderate volume and swelling to a full-bodied forte. Throughout, she

displayed masterful use of portamento, crafting arching lines which were often achingly

beautiful. And she called forth some steel in her tone and starch in her demeanor as needed to

drive the drama forward in her important confrontational declamations.

If this seasoned soprano seems to employ a few small “tricks” these days, like slightly veiling

soft high notes that are approached with a leap rather than a scale progression, and pacing her

volume here and there to conserve her full arsenal for the “money” sections, it is very minor

quibbling. Mariella Devia has all of the goods (and some to spare) to successfully take on this

demanding role and make a notable star turn out of it. The Milanese public rewarded her with a

deafening appreciation at final curtain.

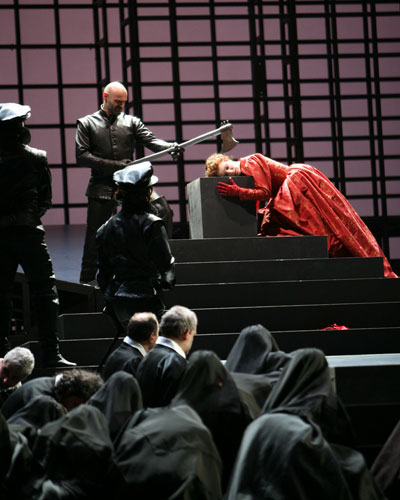

Mariella Devia, Anna Caterina Antonacci, Francesco Meli, Carlo Cigni (Act I)

Happily, we were just as lucky with our other queen, in the guise of Anna Caterina Antonacci’s

“Elisabetta.” The tall, lanky, and beautiful Ms. Antonacci was every bit her rival’s equal,

proving to be a perfect foil physically and musically. For ACA has a rangy, disciplined, highly

individual, and powerful voice, with a fair measure of metal — and a big measure of mettle —

driven by technical mastery. This “seconda donna” also scored big with the vociferously

appreciative crowd for her imposing glamorous star presence as much as for an imperious

outpouring of focused sound.

The program book referred to a past successful (1971) Scala production of “Maria Stuarda” with

the established stars Shirley Verrett and Montserrat Cabelle. It couldn’t help but provoke my

comparing “what was” to “what is” and I have to say that Mesdames Devia and Antonacci

seemed to more than hold their own up against such a previous fabled pairing. Blessed is the

house that can find two complementary divas of such stature, not once, but now twice in its

recent history. Bravi.

The scheduled tenor Francesco Meli was indisposed, so “Leicester” was capably assumed by

Dario Schmunck. Mr. Schmunck is currently singing such things as “Elvino,” “Alfredo, “ and

“Leicester” around European houses, and was already scheduled for it at La Scala later in the run.

He is possessed of a perfectly pleasant lyric voice which he uses intelligently.

In a major house as this, I thought he would be, say, a perfect “Cassio,” but “Leicester” is

decidedly a much bigger “sing,” calling for leading man star quality and panache that he does not

yet quite fully possess.

His first aria was greeted with a derogatory comment (shouted by one of the claquers?), and he

certainly did not deserve that. His enjoyable performance does still seem a work in progress, and

while unfailingly pleasant and well-sung, Schmunck was not quite on a level of fire power with

our two queens, from whom he notably took considerable inspiration in each of the separate

duets.

Piero Terranova’s “Cecil” began somewhat tentatively. Indeed in Act One, his important solo

rants were curiously weak-voiced and covered by the orchestra. Thankfully, he progressively

found his stride, and by Act Three he was offering compelling, full-throated singing. “Cecil”

may be a comparatively small role, but he fuels so much of the conflict that it was welcome for

Terranova to come to the party in due course.

Carlo Cigni brought beauty and amplitude of tone, fine vocal presence, and sincere acting to

“Talbot.” In the minor role of “Anna,” Paola Gardina displayed an uncommonly beautiful voice,

one not usually lavished on such a small part. I look forward to encountering both Cigni and

Gardina in future performances and larger assignments. The exemplary choral work was

prepared by Bruno Casoni.

Musical values were of a very high standard. Maestro Antonio Fogliani led the excellent resident

orchestra in a taut, largely unsentimental reading, that still allowed for breadth of utterance as

well as touching, highly introspective musings such as in the famous Act III prayer. Especially in

the sextet and the larger choral moments, Fogliani commanded admirably clean control of his

assembled forces to exciting musical effect.

The venerable Pier Luigi Pizzi did his usual triple duty as set designer, costume designer, and

director. The costumes were sumptuous, character-specific, evocative if not slavishly

“period-correct,” and meaningful. His Elizabeth-as-Fashionista “take” worked well, and

Antonacci seemed to revel in her spiffy duds. Mary’s silvery-black frock may have had the

required austerity but it was elegantly handsome; and topping all else in the show, her spectacular

red dress for the final prayer and execution (forgive me) was to die for.

The handsome, functional set was framed within a sort of “box” of industrial scaffolding that

suggested a prison. Centered within it were gradated stepped platforms, shaped rather like an

Incan pyramid, the top level of which was joined to perimeter walkways by three symmetrical

ramps. By using different lighting washes on the cyclorama, many evocative silhouettes could be

created. However, Mr. Pizzi’s floor plan did tend to restrict traffic patterns to a certain sameness

of movement for the larger scenes.

Pizzi created a truly brilliant effect for the garden, in which we first encounter Queen Mary. The

“pyramid” having been surreptitiously retracted, a full grove of life-like trees rises from

underneath the stage like a veritable “dawn” of greenery, including an astro-turfed “bank” on

which Mary can luxuriate and stroll. Other than this beautifully calculated forest, the overall unit

setting was not intended to communicate a literal sense of time or place, but it was very pleasing

to look at and functional.

Anna Caterina Antonacci (Elisabetta)

Anna Caterina Antonacci (Elisabetta)

The prison metaphor not only worked for the obvious enclosure of Mary, but suggested that

“Elisabetta” was perhaps in her own “prison,” being constrained by the royal behavior and

sometimes unpleasant duties expected of rulers. Part of the design concept was creating a sort of

“living sculpture,” peopling this setting with omnipresent guards who prowled the structure

brandishing torches. This leather clad, eye candy ensemble of strapping young men may not

have added all that much, but neither did it unduly distract.

The high accomplishments of Pizzi the designer were not quite matched by Pizzi the director. I

am grateful indeed that there was no bizarre “concept” imposed, that the groupings and stage

placement were always serviceable and the movement cleanly competent, all of which told the

story and allowed the artists to sing their best. And, yes, that famously bitchy duet scene between

the two queens certainly made its full mark, and there were some lovely personalized touches

overall.

Still, I had the feeling that there was more to be mined dramatically out of two such wonderful

sopranos, especially the always creative Ms. Antonacci, whose “Elisabetta” seemed to settle for

two-dimensions when my experience with her in past performances has shown she is fully

capable of three (or more).

The one concession to modest “innovation” was that during the opening bars of the first scene, a

pantomime was created in which our heroine is given communion by “Talbot,” effectively

establishing her faith-based credentials and defining her predicament. (Although, since she later

unceremoniously and rousingly calls her cousin a “vile bastard,” I was thinking: “And you take

communion with that mouth, Miss Mary?”)

It has been said that acting is really listening. . .and re-acting. And here I think lay a (fixable)

minor shortcoming of the production. Characters aren’t consistently listening to each other. And

reacting. The above mentioned epithet may be the most glaring (but not only) example, for after

“Maria” hurled “Vil bastarda!” at “Elisabetta,” there was scant-to-no-reaction, with “Anna”

actually just remaining complacently seated. I mean, the take-no-prisoners Queen has just been

insulted (all right, all right, she has taken one or there would be no story)! I would hope that

some minor tweaking and enhanced character interplay could be instilled that could make an

already fine evening even finer.

In past years, much ink has been spilled and hands wrung about the state of the art at La Scala.

At least based on this visit, its reputation as one of the world’s leading opera houses has

emphatically been sustained. A tour of their adjacent museum was revelatory as to how this lofty

regard came to be established in the first place, since it contains numerous terrific portraits,

photos, mementos, props, scores, letters, and instruments touched by many (perhaps most) of the

greatest composers and interpreters of the last 200 years of operatic history, all of whom gifted

their musical talents to La Scala.

Scene from Act II

It is also telling that, currently on view, there is a special display of costumes worn by Maria

Callas for all the roles she performed at the house. This remembrance of the thirtieth anniversary

of her death offered a reminder, should any be needed, that we would not perhaps be hearing

“Maria Stuarda” and a good deal of the bel canto repertoire in wide performance today were it

not for La Divina’s blinding talent and trail-blazing musical advocacy.

Maria may be gone but it seems La Scala can still summon up greatness, as Mariella Devia and

company aptly demonstrated. The Queen is dead. Long live the Queen.

James Sohre

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Maria_Stuarda_Devia.png

image_description=Mariella Devia as Maria Stuarda (Photo by Marco Brescia courtesy of Teatro alla Scala)

product=yes

product_title=Gaetano Donizetti: Maria Stuarda

product_by=Above: Mariella Devia (Maria Stuarda)

All photos by Marco Brescia courtesy of Teatro alla Scala