Luckily, at its heart we were privileged to have a soprano with true star quality, the radiant Karina Gauvin. Ms. Gauvin has a well-deserved reputation for pre-eminence in this Fach and it is easy to see why. Her lustrous, honeyed instrument is wedded to a refined technique that handily surmounts any obstacle the composer has invented. Well-colored dramatic outbursts? Check. Clean trills and coloratura with inner life? Check.

Check. Melting cantilenas, supreme arching legato phrases, rich chest voice? Check. Check. And Check.

And while she commands the style with precision and authenticity, Karina avoids the pitfalls of preciousness and correctness that can sometimes handicap such period efforts. Her Armide was a living, breathing, emoting woman that happened to flawlessly represent her story in Gluck’s musical vocabulary. Hers was a towering achievement.

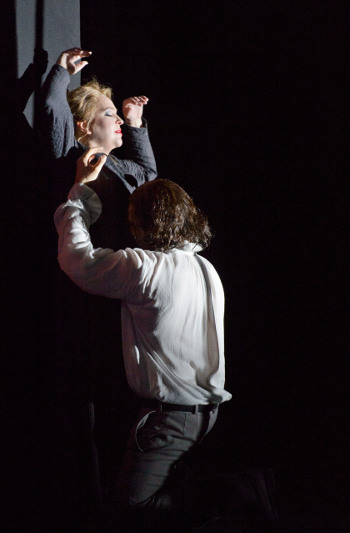

Karina Gauvin as Armide and FrÈdÈric Antoun as Renaud

Karina Gauvin as Armide and FrÈdÈric Antoun as Renaud

She was well-matched by FrÈdÈric Antoun as the dashing Renaud who is the object of her conflicted love-hate musings. Mr. Antoun’s lightly veiled, medium weight, freely produced tenor is an exact match for the role. The tonal production is well-connected from low to (very) high and he rides the breath with ease. He delivers yummy, haunting phrases when in love, and colors his declarations with appropriate scorn when freed from the spell. Although Ms. Gauvin’s vocal presence was marginally more forthcoming, the two partnered each other well in the extended duets,

As Armide’s confidantes, Karin Strobos (PhÈnice) and Ana Quintans (Sidonie) set off sparks with their assured, bravura delivery. Ms. Strobos’ youthful mezzo was cleanly produced with a hint of darkness, and her spunky stage presence enlivened every scene she was in. Ms. Quintans’ accurate soprano brought a welcome soubrette-ish brightness to the proceedings. This worked exceedingly well for her as Sidonie, but she was cast in multiple roles to include Naiad, Shepherdess (where her bright delivery worked), as well as the Demon in the Figure of MÈlisse (where it worked less well, a bit more vocal heft being ideal).

Henk Neven drew a good distinction between his dual roles as the tormented Aronte and the swaggering Ubalde. As the latter, he provided some of the evening’s best French, revealing a creamy baritone that was robust at full voice and meltingly effective in half voice. Alas, SÈbastein Droy could not match this double duty feat as ArtÈmidore and the Danish Knight. His muffled tenor seemed short on top, and he kept the volume knob turned to mezzo forte either by choice or of necessity. As Hidraot, Andrew Foster-Williams’ good dramatic intent and hectoring delivery could not quite compensate for a somewhat woolly bass-baritone.

I have always loved the generous artist Diana Montague, but here she seemed miscast as Hate. Her beautiful styling, freely produced mezzo, and innate musicality were everywhere in evidence but the role seemed to require singer capable of a searing Cossotto tirade rather than a controlled lyrical reprimand. Francesca Russo Ermolli made a lovely impression late in the piece as Pleasure, her poised, pure tone gently beguiling us.

Ivor Bolton has few equals in this repertoire and he drew forth thrilling sounds from his band of instrumentalists. Whether as a tightly knit ensemble or featured in remarkable solos, this was a first class effort from the pit (the principal flute was just remarkable all night long). Nicholas Jenkins chorus was no less exciting, and their dramatic commitment was awesome, yes that’s the word. Nonetheless there were a couple of instances when chorus and orchestra were internally together, but there was a split second disparity between stage and pit. This was also true with Act IV, when Ubalde and the Danish Kinight seemed periodically, stubbornly out of sync. Since the musical perfection was ninety-nine per cent a given, I can only imagine there was an acoustic issue with the wide-open setting and its lack of reflective surfaces, the manic staging that was imposed on the piece, the upstage placement of the performers, or all three.

Hysterical (or at times sardonic) laughter, swords hurled to the ground, pregnant pauses, manic splashing in a pond. . .do these jump to mind when contemplating Gluck’s Armide? Because they evidently did to director Barrie Kosky. Katrin Lea Tag has designed a basic setting of a wide swath of lumpy turf that fills the center two thirds of the apron with a rather scruffy tree sprouting stage right. Armide, clad in a simple, wholly unremarkable black dress spends so much time posed by that single set piece, I half expected her to channel Lady Bird Johnson and urge us to “plant a tree, a shrub, a bush. . .”

SÈbastien Droy as Le Chevalier Danois and FrÈdÈric Antoun as Renaud

SÈbastien Droy as Le Chevalier Danois and FrÈdÈric Antoun as Renaud

Renaud’s enchantment is a curious ‘affair’ indeed. He ends his first solo asleep face down by the tree, so Armide becomes smitten with him solely from regarding his firm, um, torso, as she clings to the tree in perhaps too phallic a manner. As he became bewitched, they did a slooooooo-moooooo pas de deux that found them stroking faces, hair and arms over and over and over again. And over. Again. Then as the piece ended to deafening silence, they slunk to the right proscenium (presumably to stroke it) as Mr. Bolton waited and waited. And. Waited.

The Maestro’s body language suggested he got either amused or irritated that musical set pieces excellently performed got no applause, but truth to tell there was not one visual “button” to prompt a response. Two weeks prior, I was privileged to see a brand new opera that got frequent applause because the creative team (and composer) cued us when a section was finished. The repeated uses of long pauses was a considerable miscalculation, sapping the musical impetus, and distorting the shape. I mean these were long enough pauses to make Harold Pinter yell “get on with it!” Since there is no compensating dramatic revelation, I would urge eliminating them.

Ms. Tag’s setting eventually reveals the entire stage, with a large rectangular pool of water, and a scattering of trees. This had promise, perhaps only because this garden was a relief from the bleak desert. There was certainly little to fault with Franck Evin’s brilliant (pun intended) lighting design. Mr. Evin used harsh down- and cross-lighting to fine purpose and selectively added in color filters that enhanced the mood and emotion. The only mis-step was that Renaud sang much of one solo entirely in the dark while Mr. Kosky chose to illuminate extras who were noisily splashing in the pond behind.

This manic frolicking in the water was used on many occasions perhaps to distract us from the fact that the principals were not very well-directed and their character relationships were not well-developed. At one point, Armide’s two confidantes kick up water tirelessly while poor Ms. Gauvin tries gamely to sing over it. Another moment found the chorus clumped together slogging en masse through the pond from stage left to right while jerking their heads like pigeons on acid. Oh, and when in doubt of how to show actors are dramatically involved, make them throw swords clanking to the ground. No kidding, the metal met the road this way countless times over the long-ish evening.

Ms. Tag the set designer made a better presentation than Ms. Tag the costume designer. It is not her fault that her set was frequently ill-used. But it is her fault that the disparate assortment of clothing made little sense nor a unified statement. Some of it, like the schmatte foisted on Sidonie, looked like it might be beachwear covered by a weird wrap. Hidraot was attired in a paraphrase of kilts. Or was it a plaid 1950’s girl’s tartan skirt? At least the two knights looked like knights and Renaud looked heroic. What was up with bare-chested Aronte and the clinging white pants with a blood stain suggesting his manhood had been cut off? The fact that he a) was still singing baritone and b) was filling out the revealing trousers quite well thank you, suggested that Mrs. Aronte is/was a lucky woman.

FrÈdÈric Antoun as Renaud

FrÈdÈric Antoun as Renaud

One scene that almost worked in spite of itself was Hate’s entrance. With much laying on of mist after a rainstorm upstage, a group of male choristers crept on and pinned Armide onto her back on a hillock. Clad in ominous black period suits, with neck ruffs and sort of Baron von Richthofen aviator skull caps, eventually the men hold her legs spread, and she gives birth to Hate with Ms. Montague crawling into view from a trap door under her skirts. Quite a stunning, wow moment. But then the female chorus rushed on dressed identically in straight blond wigs, neon pink (sort of) business suits, and black vinyl boots. And the entire chorus twitched like they were choreographed by St. Vitus. I can only applaud their dedication and hard work even as I scratch my head as to how such a great moment was just thrown away with undisciplined excess.

When not splashing or twitching, characters engaged in inappropriate laughter. Armide is first made to cackle in anticipation of snaring Renaud, who ultimately laughs at Armide when he rejects her. There is choral laughter a number of times, perhaps most memorably when an effigy of Armide is hung by the neck and sent swinging near the end of Act I. Maybe they are tickled because it looks like an effect purchased at a Down in the Valley fire sale? This dummy gets swung back into action in Act II by which time we could have all used a good laugh.

In furthering the belief that nothing exceeds like excess, there is an endless rain of confetti late in the first half that starts out being quite dazzling and goes on until we are good and tired of it. But why stop? The second half begins with an endless rain of pink and red confetti, that outlives the Energizer Bunny. The lovely waltz late in the evening is not treated to proper ballet, but rather finds the cast paired off, slow-dancing in the pond like last call at the Junior prom. And when the music ends, they forget to tell the cast who keep swaying for another 30 seconds, well, just because they can.

In a final cynical decision, the production brings an old naked couple into the scene, I guess to nail home the idea to Renaud that this is what relationships will lead to, sagging bits and bobs and disorientation. By the time the glorious Ms. Gauvin gets stranded motionless on a dune, with all other distractions stilled, beautifully interpreting her final aria almost motionless as in a concert, I was thinking, “a concert. . .gee. . .if only.”

James Sohre

Cast and production information:

Armide: Karina Gauvin; Hidraot: Andrew Foster-Williams; Renaud: FrÈdÈric Antoun; ArtÈmidore/Danish Knight: SÈbastein Droy; Ubalde/Aronte: Henk Neven; Sidonie/Nayad/Shepherdess/Demon in the figure of MÈlisse: Ana Quintans; PhÈnice: Karin Strobos; Hate: Diana Montague; A Pleasure: Francesca Russo Ermolli; Conductor: Ivor Bolton; Director: Barrie Kosky; Set and Costume Design: Katrin Lea Tag; Lighting Design: Franck Evin; Chorus Master: Nicholas Jenkins

image=http://www.operatoday.com/armide_172.png

image_description=Diana Montague as La Haine and Karina Gauvin as Armide [Photo by Monika Rittershaus courtesy of De Nederlandse Opera]

product=yes

product_title=Armide, Amsterdam

product_by=A review by James Sohre

product_id=Above: Diana Montague as La Haine and Karina Gauvin as Armide

Photos by Monika Rittershaus courtesy of De Nederlandse Opera