As Dutch National Opera’s most successful export ever, it gets to be the only

revival in the company’s celebratory 50th season. Eighteen

years on, it is still overwhelming.

Musically, this revival is equally worthy of the 1957 masterpiece about the

Carmelite nuns guillotined in 1794 during the Reign of Terror for refusing to

renounce religious life. The Residentie Orkest under Stéphane Denève

was nothing short of inspired. Wind solos wept quietly. The brass section,

crucial in expressing anxiety churning itself into blind terror, distinguished

itself, forgetting the odd rogue note, with honed technique and supreme

control. Mr Denève kept things transparent, in service to the words. He

conducted the interludes with elegant restraint and his graded build-up to the

final horror had the feel of a superior thriller. In fact, Georges

Bernanos’s play was written for the screen, and the opera’s

division into twelve scenes, some of which start in mid-conversation, is partly

why its structure feels so modern and familiar. No doubt Mr Denève’s

pacing was the result of long study, but it came across as instinctive and

uncontrived.

Doris Soffel as Madame de Croissy and Sally Matthews as Blanche

Doris Soffel as Madame de Croissy and Sally Matthews as Blanche

The whole cast, meticulously directed by Mr Carsen, gave theatrically acute

performances, without as much as an eyebrow raised gratuitously. All the

shorter roles were well-sung. Michael Colvin made a convincing Chaplain.

The women of the Dutch National Opera Chorus were top-notch, joining the

soloists in a refulgent Act II Ave Maria and a note-perfect closing Salve

Regina. Jean-François Lapointe and Stanislas de Barbeyrac as,

respectively, Blanche’s father and brother, were both forceful and

vocally rock-solid. Mr De Barbeyrac’s expressive dynamics made the

Chevalier’s visit to his sister in the convent stand out as one of the

more memorable scenes.

Sally Matthews injected the fearful, hypersensitive Blanche with toe-curling

awkwardness, accentuating her self-hatred rather than her timidity. Vocally,

her middle-to-lower range sounded clotted, but her missile-like top went a long

way towards conveying the panic that has the novice nun in her grip. Michelle

Breedt’s Mother Marie was probably caught on a lesser night. Upward

climbs were marred by skidding and her lower notes did not project freely

enough for this overbearing character. Mother Marie is, after all, the one who

persuades the sisters to take a vow of martyrdom, although she herself is

denied that glory. It would be useless to analyze where Doris Soffel’s

mezzo-soprano tends to shake and spread—her Old Prioress was simply

grand, every word thrumming with meaning, her dying howls terrifying. A frail

woman brimming with tenderness one moment, a vocal tornado railing against God

the next, Ms Soffel’s moribund nun was the stuff of nightmares, and of

great moments at the opera. No less impressive was Sabine Devieilhe as that

pious equivalent of the flibbertigibbet, Sister Constance. She propelled her

laser-sharp soprano with a thrust that far exceeded its size and her text

clarity and physical energy were a complete joy. Making her DNO debut, Adrianne

Pieczonka brought vocal beauty and dignity to the role of Madame Lidoine. Her

highest notes did not always come easily, but her ariosos, wrapped in the

velvet of her luxurious timbre, revealed a deeply touching, motherly

Prioress.

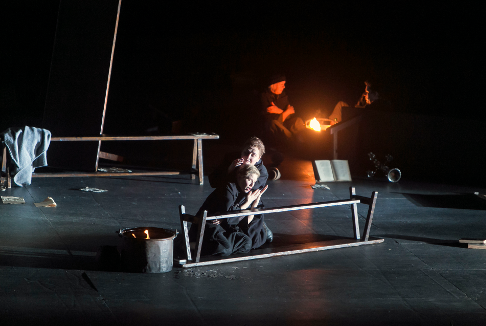

Michelle Breedt as MËre Marie and Sally Matthews as Blanche

Michelle Breedt as MËre Marie and Sally Matthews as Blanche

Mr Carsen’s production affects with its simplicity, which belies a

wealth of detail. The way the nuns lie face down around Madame de

Croissy’s death bed, for example. It is the same position nuns assume

when taking their vows and here it presages their death, while drawing a

parallel between Blanche’s decision to die with them and her commitment

to the order. Mr Carsen finds true poetry in his subjects, in the draping of

their habits and the tranquil mechanics of their daily chores. As

Poulenc’s music darts in and out of their inner life, Mr Carsen confines

and opens spaces with minimal demarcations, such as spotlights and candles. The

biggest barriers are human: the row of nuns forming a grille between Blanche

and her brother, the angry crowd sweeping across the stage leaving disorder in

its wake. In the end, the safest refuge is also human, not topographical. As

Madame Lidoine says in her prison speech: “No one could take away from us

the freedom that we surrendered with our vows so long ago.” By choosing a

common destiny, the nuns conquer their fear. Despite the savage swipes of the

guillotine, their Salve Regina rises in hopeful phrases. Their final prayer is

an Ascension as well as an execution and staging it as an ethereal dance is

pure genius.

Jenny Camilleri

Cast and production information:

Blanche: Sally Matthews, Le Marquis de la Force: Jean-François

Lapointe, Le Chevalier: Stanislas de Barbeyrac, L’Aumônier du Carmel:

Michael Colvin, Geôlier: Jean-Luc Ballestra, Madame de Croissy: Doris

Soffel, Madame Lidoine: Adrianne Pieczonka, Mère Marie— Michelle

Breedt, Soeur Constance de Saint Denis: Sabine Devieilhe, Mère Jeanne:

Virpi Räisänen, Soeur Mathilde: Wilke te Brummelstroete, Officier:

Roger Smeets, 1er Commissaire: Mark Omvlee, 2ième Commissaire: Harry

Teeuwen, Thierry: Michael Wilmering, M. Javelinot: Sander Heutinck, Conductor:

Stéphane Denève, Director: Robert Carsen, , Set Designer: Michael

Levine, Costume Designer: Falk Bauer, Lighting Designer: Jean Kalman,

Choreographer: Philippe Giraudeau, Dramaturge: Ian Burton, Dutch National Opera

Choir, Residentie Orkest. Seen at Dutch National Opera & Ballet, Amsterdam,

Saturday, 7th November 2015.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/dno_dialogues_-_a4-300dpi.png

image_description=Dialogues des CarmÈlites [Photo: Petrovsky & Ramone]

product=yes

product_title=Dialogues des Carmélites Revival at Dutch National Opera

product_by=A review by Jenny Camilleri

product_id=Above: Dialogues des CarmÈlites [Photo: Petrovsky & Ramone]

All other photos by Hans van den Bogaard