In recent years, there has been a tendency with many of Glass’s scores (one

thinks of the First Violin Concerto, for example) to revisit his tempos and

this was very notable in the pacing of the opera this time round. It made

for a very long evening, but the upside was a transformation in the music

that added much needed depth and emotional integrity to a work that

sometimes seems to be missing both. A downside, of course, is that in an

opera that really has such minimal narrative to keep it moving one’s

concentration and endurance is tested to the limits. This sometimes felt

like Parsifal on benzodiazepine, or an over-dramatized Bach

oratorio – but it is to the credit of a splendid cast and a brilliantly

engaged conductor that this performance was so spellbinding. For a first

night, which so often isn’t perfect, this was as close to ideal as I’ve

heard in many years.

If Satyagraha is the best of the three profile operas it is

largely because it has neither the astringency ofEinstein on the Beach nor the monotonal repetitiveness of Akhnaten. Minimalism can sometimes sound very temporal and hollow,

but here at such a broad tempo (take, for example, the scene in Act II with

the burning of the passes which could have almost been lifted from the

pages of re-orchestrated Bach) and the effect was transcendental. That is

not to say that the score doesn’t motor onwards like a typewriter – the

male chorus, with their taunts of “Ha! Ha! Ha!” were acidic against the ENO

woodwind – not always exactly synchronised – but this is a long scene and

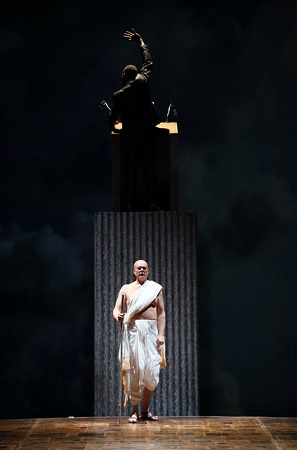

hugely demanding. The closing pages of Act III, where Gandhi stands beneath

the plinth of Martin Luther King against darkening clouds that foreshadow

the assassinations of both men, was devastating, yet taken at this chosen

speed you felt it was never-ending. The music felt as oppressive as the

bleakness of the imagery on stage; chromatic shifts in key from the

orchestra were like changing projected film slides on a permanent loop.

For a composer so heavily involved in composing for film, it’s perhaps not

surprising that ENO’s production of Satyagraha should acknowledge

that debt, however tangentially. Whether it’s a steamship rolling slowly

across the corrugated steel that remains the constant backdrop for this

staging, or film of civil rights marches in support of King’s speech, the

camera is both a means of projection and a means of communication. Before

film, there was newspaper and here it is reimagined in every possible way.

It is used as a means of peaceful protest, it is used as a means of

violence, where the male chorus “stone” Gandhi into submission. It is used

as a backdrop against which Sanskrit words are projected, it is used to

cultivate fear and terror, where unspeakable violence is carried out behind

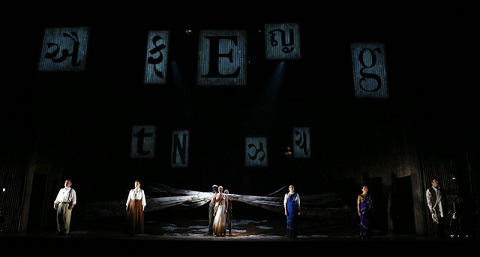

curtains of newspaper in the darkness of the shadows. Before newspapers,

there was just the word. Great tablets inscribed with single Sanskrit

letters descend like monolithic slabs that recall the Ten Commandments.

ENO, Satyagraha Photo credit: Douglas Cooper.

ENO, Satyagraha Photo credit: Douglas Cooper.

Phelim McDermott and Julian Crouch, the director and designer of this

production, have made this opera as theatrical as possible to stem the

awkwardness of its lack of narrative. There is an overwhelming sense of

austerity, poverty and hardship to the corrugated township of late

nineteenth century and early twentieth century South Africa here – and it

even extends to the muddied, frayed bottoms of the women’s long dresses as

they are dragged through the dirt. The attention to detail misses very

little. This is a recycled staging, where the wicker baskets of Tolstoy

Farm are magically transformed into giant fish, where torn and scrunched up

newspapers are turned into huge monsters and disfigured puppets and where

endless streams of sticky tape that served firstly as a fence are then torn

down and folded like origami into a giant stick figure of a hangman. You

are often awestruck by the acrobatics of Skills Ensemble. Not everything

was perfect, but when it worked you couldn’t take your eyes off it. A scene

where an image of the earth, spinning like a globe, appeared on a round

table, for it and one of the performers, to slowly be lifted towards the

roof of the stage was stunning.

Despite these sweepingly dramatic moments, so much of Satyagraha

remains static. This production doesn’t wear its philosophy lightly.

Excerpts from the Gita, or the principles of ‘truth force’ pepper the

walls, like religious graffiti. Reading them is a form of stasis in itself.

The arrest of the protestors in Act III is symptomatic of the opera’s

glacial pacing. The armed soldiers could have been wading through treacle,

yet it was oddly balletic to watch. For much of Act II Gandhi doesn’t

actually sing a note of music – he wanders the stage like a prophet, and

yet it was compelling to watch. The Act II burning of the passes seemed

interminable, and would have been had it not been for the absolutely superb

playing of the ENO orchestra who brought such intensity to the whole scene.

King’s transformation at the end of Act III into a great orator was

entirely mimed, and yet for almost twenty minutes you were transfixed as if

you were watching a silent movie.

Toby Spence. Photo credit: Douglas Cooper.

Toby Spence. Photo credit: Douglas Cooper.

So to the singing, which I found to be first rate. Toby Spence, singing the

role of Gandhi for the first time, was compelling in the title role. The

part of Gandhi is difficult because for large sections of the opera the

tenor isn’t singing – though he is on stage. Spence is undeniably

impressive – he transforms from young lawyer in Act I to philosopher and

emerging prophet in the rest of the opera with convincing believability.

The voice isn’t stentorian (I don’t think this role really requires that

kind of singing), but there is pathos, humanity and deep insight to his

interpretation. He is also a formidable stage actor, which isn’t something

one should take for granted with an opera singer.

Nicholas Folwell, Charlotte Beament, Toby Spence, Anna-Clare Monk, Stephanie Marshall, Clive Bayley. Photo credit: Douglas Cooper.

Nicholas Folwell, Charlotte Beament, Toby Spence, Anna-Clare Monk, Stephanie Marshall, Clive Bayley. Photo credit: Douglas Cooper.

Commanding as Kasturbai was the Canadian mezzo, Stephanie Marshall. The

voice is both huge and rich, and this was a powerful assumption of the role

of Gandhi’s wife. Charlotte Beament, as Miss Schlesen, Gandhi’s secretary,

sounded a touch tentative at first but her brilliant and bright soprano was

able to cut through the orchestra like glass. The composer is rather

merciless in his demands for this particular role, since so much of it lies

in the upper registers of the voice, but Ms Beament was often

breath-taking, and her soprano is fresh enough to hold those high notes

without the notes cutting short. By any standards, this was outstanding

singing. Andri Bjˆrn RÛbertsson, as Lord Krishna, sang magnificently, but

was less compelling to watch I’m afraid. Nicholas Folwell as Mr Kallenbach

seemed less secure when singing solo, where the voice appeared small, than

he did when singing as part of an ensemble, where he largely excelled.

Karen Kamensek, the conductor, is something of a Philip Glass specialist,

and it showed. Her command of the score was almost absolute, and she

obtained from the Orchestra of English National Opera playing that was

meticulous, sumptuous and impressively coherent. It’s one thing to get the

notes in something like the right order; it’s quite another to make this

score sound as deeply involving and as profound as Ms Kamensek achieved

here. This was a major achievement for her and the ENO orchestra, who

should probably now be considered one of the leading opera orchestras for

Glass’s major works.

ENO’s Satyagraha was a major operatic landmark when it was first

performed over a decade ago. It is still that – and absolutely unmissable.

Marc Bridle

Philip Glass: Satyagraha

Toby Spence – M. K. Gandhi, Charlotte Beament – Miss Schlesen, Anna-Clare

Monk – Mrs Naidoo, Stephanie Marshall – Kasturbai, Nicholas Folwell – Mr

Kallenbach, Sarah Pring – Mrs Alexander, Eddie Wade – Prince Arjuna, Clive

Bayley – Parsi Rustomji, Andri Bjˆrn RÛbertsson – Lord Krishna, Skills

Ensemble; Production: Director – Phelim McDermott,

Associate Director & Set Designer – Julian Crouch, Revival Producer –

Peter Relton, Costumes – Kevin Pollard, Lighting – Paule Constable, Video –

Leo Warner, Mark Grimmer (Fifty Nine Productions),English National Opera

Orchestra & Chorus, Karen Kamensek (conductor)

ENO, The Coliseum, London; 1st February 2018.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/ENO%20Satyagraha%20%28c%29%20Donald%20Cooper%20%281%29.jpeg

image_description=Satyagraha, English National Opera

product=yes

product_title=Satyagraha, English National Opera

product_by=A review by Marc Bridle

product_id=Above: Toby Spence and ENO company, Satyagraha

Photo credit: Douglas Cooper