Bruch (1838-1920) may be best known for his Violin Concerto no 1, but this first ever recording of his full opera should broaden interest in his output as a whole. Bruch’s Die Loreley is a very early work indeed, written between 1860 and 1863, and shows how the composer responded to the influences around him. The text, by eminent poet Emanuel Geibel (1815-1884), was conceived for Felix Mendelssohn, whose music Geibel loved dearly. He so identified the text with Mendelssohn that he was reluctant to give Bruch permission to use the libretto. But Bruch (in an era before copyright enforcement) was not deterred. The Mendelssohn connection is significant, because it shows the context in which the opera was written, which shapes the way in which the opera should be assessed. Far from being retrogressive, Bruch was in tune with the values of German music theatre, as represented by Mendelssohn, Carl von Weber, Heinrich Marshner (whose 1833 opera Hans Heiling addresses the Lorelei legend) and even Robert Schumann. Though Bruch’s Die Loreley doesn’t, understandably, have the astonishing originality of mid and late period Wagner, it can be heard as a young composer’s response to the “new”, heralded by Richard Wagner.

Immortalized by Heinrich Heine’s poem Die Lorelei (1822) the Lorelei legend epitomizes the aesthetic of the early Romantic era, where Nature spirits inhabit idyllic landscapes where humans encounter extraordinary adventures. Seduced by beauty, mortals meet their doom. The Romantic spirit wasn’t “romantic”, but haunted by a sense of death, mystery and inevitable change. In Heine’s words, “Ich weifl nicht, was soll es bedeuten, Dafl ich so traurig bin”.

In Geibel’s libretto, Leonore, (sung by Michaela Kaune), daughter of a ferryman who works on the Rhine, sings a love song for a hero of her dreams, as she sits on a rock above the river. Hearing her voice, Pfalzgraf Otto (Thomas Mohr) becomes entranced, but he’s due to be married the next day to Bertha the Gr‰fin von Staleck. Leonore is so pure that when she sings, she’s accompanied by an angelic chorus who sing the Ave Maria. Leonore lives in a world of the imagination, so Geibel introduces, for contrast, Leonore’s father Hubert (Sebastien Campione), the boatmen and the vintners, busy at work on the river bank. Bruch uses energetic, simple rhythms to suggest physical labour and stability, with choruses for men, women and combined voices. A procession passes by, bearing Gr‰fin Bertha (Magdalena Hinterdobler,) who is loved by the villagers for her kindness. Banners fly, and presumably horses prance, suggested by jaunty march.

Act II is short, but pivotal. A storm gathers and the Spirits of the Rhine rise up from the waters.; Surging figures in the orchestra evoke Mendelssohn, choral lines swaying wildly. Heartbreak has changed Leonore’s personality. She calls on the Spirits to avenge her : they echo her words, leading her on. “Mein Herz versteine wie dieser Felsen!” If she cannot have Otto, her heart will turn to stone. She throws her golden ring to the Spirits and pledges herself to them if they’ll enact a curse on the unwary. In Geibel’s version, Leonore herself initiates the curse, and suffers for it., and the Spirits of the Rhine are both male and female. In Wagner’s Der Ring der Neibelungen, the Rhinemaidens were innocents, tricked by Alberich, who placed a curse on the Rheingold. But such is the nature of art : each approach to the legend inspires new ideas.

In the Pflazgraf’s castle, the wedding feast is being celebrated with cheerful choruses. A Minnes‰nger, Reinald (the veteran Jan-Hedrik Rootering, still in good form) sings of love and fidelity. Otto is terrified, but no-one knows why. Suddenly, Leonore materializes, singing the song of the Loreley. Otto can hold himself back no longer and claims Leonore, raving and starting a fight among the knights. The Archbishop (Thomas Hamberger) and priests accuse Leonore of witchcraft and have her sent, in chains, for trial. But she sings her defence so beautifully that all who hear it are enchanted. Otto still rages, and is excommunicated and driven away. Bertha dies of a broken heart. In Hubert’s village, the boatmen and vintners mourn her. Otto sits outside the church , hearing their hymns but still cannot escape the curse. He heads back to the rock where he first encountered Leonore , begging her forgiveness, but she’s no longer of his world, her lines plaintive and keening. “Zwischen dir und mir steht einfort eine dunkele Macht. The orchestra surges, and the Spirits of the Rhine well up around her. Their curse is fulfilled, and they claim her for their own, the “Kˆningin vom Rhein”.

Given the connection between Geibel and Mendelssohn, it’s almost impossible not to hear echoes of Mendelssohn in Bruch’s score, though it’s clear that Bruch was responding to Wagner, with echoes of Tannh‰user, and to much else popular in the period. Geibel’s libretto for Die Loreley is superb, so well written that Bruch can set each scene to catch the atmosphere. The Grand Scene of the Spirits, which forms the Second Act, is quite an achievement for a composer in his early 20’s. Though the opera is not a major milestone, it is well worth hearing as part of the evolution of German music theatre in this period. Stefan Bunier and the M¸nchner Rundfunkorchester give a rousing account, which probably won’t be improved upon for some time, since the opera was only recently revived in full. A good cast all round. Kaune and Mohr are particularly impressive, she at turns meek and ferocious, malevolent and wistful, epitomizing the complexity of Leonore’s character. Mohr’s clear tenor rings as though Otto were a hero, which he is, in a way, since he was cursed through no real fault of his own.

Anne Ozorio

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Loreley_front.jpg

image_description=

product=yes

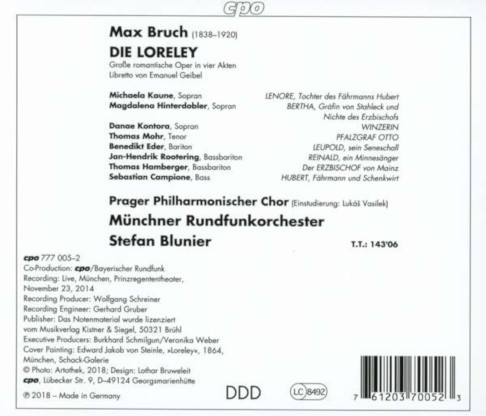

product_title=Max Bruch: Die Loreley

product_by= Stefan Blunier, M¸nchner Rundfunkorchester, Michaela Kaune, Magdalena Hinterdobler, Thomas Mohr, Jan-Hendrick Rootering Prager Philharmonischer Chor.

product_id=CPO777 005-2 [3CDs]

price=£32.89

product_url=https://amzn.to/2CyKhBs