HGO describe Partenope as an ‘opera not so seria’ and it

certainly spices seria conventions with gentle parody and

self-parody. With history and heroism losing favour with the London public,

Handel embarked on a period of experimentation that was to result in

masterpieces such as Alcina and Ariodante, and Partenope – described by Handel scholar Winton Dean as an

‘anti-heroic’ opera – was a step in this direction. One of the

first works to be produced by Handel’s newly re-organized company, it was

premiered on 24th February 1730 at the King’s Theatre.

Given the long reign of the period’s era-defining monarch, HGO’s Victorian

setting seems apt. After all, Partenope tells of a presumed

episode in the history of the mythical founding Queen of Naples, a monarch

who was just as determined as Queen Victoria – who proposed to her beloved

Prince Albert on 15th October 1839 – to take matters of love and

war into her hands. Pursued by three suitors – Arsace, Armindo and Emilio –

Partenope wears the figurative pants, while Rosmira, abandoned by Arsace,

literally dons the trousers, disguising herself as Eurimene in order to

seek revenge and win back her fickle beloved.

In a sense, the Victorians didn’t just love to be beside the seaside, they

invented it. A refuge from everyday routines, the pleasure piers offered

new entertainments – acrobats, carousels, Punch & Judy, donkey rides –

and the laced-up middle classes relished the chance to indulge in some

unbuttoned fun. The stiff-upper-lipped Brits imbibed the sea air and cast

off both their crinolines and their inhibitions in the bathing machines.

Ladies could flirt with their parasols as they flaunted their new outfits

along the promenade. The young chaps could peer through telescopes at women

descending into the sea.

And so, during the overture, when Arsace and Rosmira arrived at sands

glistening in the glare of the mid-day sun (lighting design by Daniel

Carter-Brennan), Arsace was only too pleased to kick off his tight leather

shoes, fling aside his tweeds and let his hair down in a game of beach

volley-ball with a rumbustious gang liberated by their stripy bathing

costumes. Meanwhile, Rosmira slipped out of her high-necked blouse and

ankle-length skirt into the leggings and tunic she found conveniently

hanging in a nearby changing booth, and assumed her gender-crossing

disguise.

Rachael Cox (Rosmira) and Erik Kallo (Armindo). Photo credit: Laurent Compagnon.

Rachael Cox (Rosmira) and Erik Kallo (Armindo). Photo credit: Laurent Compagnon.

In the event though, for all director Ashley Pearson’s interesting and

earnest comments about the concordance between the preoccupations of Partenope and Victorian mores – the clash between ‘strong social

morality and a desire to be free’ and between ‘public persona and private

desire’ – the action of the opera playfully took its course without the

Victorian setting contributing any significant impact or meaning. But, it

served an dramatically efficient and visually appealing purpose. Laura

Fontana’s set design had the virtues of economy and simplicity: blue and

yellow striped bathing tents formed a jolly backdrop to the strip of strand

upon which the action unfolded.

Romantic suitors played musical deckchairs as they strove to win

Partenope’s heart. Battles with buckets and spades ensued. The azure sky

remained cloud-free but the warring characters faced shadows and storms,

until female common sense unravelled the romantic knots. The arias ofPartenope are generally briefer than conventional da capo marathons and the scuffles and shenanigans whipped along

breezily. I did wonder, though, whether HGO’s decision to present the opera

(the original 1730 version) in Italian with surtitles was the right one:

given that we had travelled to one of the most English of environs, might

not the vernacular have been apt? Particularly as English text would surely

have carried clearly in the fairly small Jacksons Lane Theatre, without the

need for the tiny surtitle screen perched aloft the orchestral balcony,

upon which text was squashed in often miniscule script.

That said, the young cast – current students and alumni from the capital’s

music conservatoires – delivered some idiomatic Italian and sang with a

convincing grasp of Baroque style. Arsace is the chief object of gentle

ridicule in Partenope, but Hamish McLaren’s strong and sweet-toned

countertenor won some sympathy for the fickle waverer, communicating

Arsace’s growing self-knowledge and genuine suffering in Act 2’s ‘Fatto Ë

Amor un dio d’inferno’ and proffering a beautifully crafted plea for

forgiveness in Act 3 (‘Ch’io parta?’).

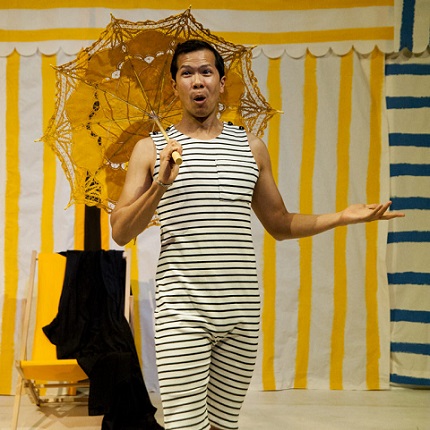

Saran Suebsantiwongse. Photo credit: Laurent Compagnon.

Saran Suebsantiwongse. Photo credit: Laurent Compagnon.

As the object of the men’s affections, Kali Hardwick was a fiery and

spirited Partenope. Her characterisation of the be-turbaned beach-queen was

sustained and compelling: all sneering eye-brows and dangerously pointed

parasols. Her soprano is clear and has a nice glint – though occasionally

she pushed it a little hard at the top, and the edge hardened into

shrillness. Hardwick has a lot of power at her disposal, but she didn’t

always judge the acoustic and sometimes over-sang. Though the coloratura of

her first aria wasn’t entirely crisp, her voice later relaxed, the

precision improved; Partenope’s Act 2 aria ‘Qual farfalletta’ was

especially moving.

Rachael Cox exhibited a lovely warm lower range as Rosmira/Eurimene and

didn’t struggle at all with a role that dips down into the deep. She sang

with a sure sense of line, musical and dramatic focus, and an overall poise

that imbued the feisty revenger with an appealing integrity of spirit.

Erik Kallo’s Armindo was a snivelling cry-baby – the dupe on a comic

picture postcard – whose shoulders hunched and drooped with self-pity.

Fortunately, his countertenor had more backbone and colour than the

character he impersonated! Kallo sang with confidence and accomplishment,

as did tenor Peter Martin as Emilio – who comes to do battle with

Partenope, and then finds himself enamoured and warring instead with the

rival suitors. Martin has a pleasing, agile tenor; he executed the

coloratura with aplomb, and alone among the cast had mastered a Baroque

trill.

Saran Suebsantiwongse’s stuffed-shirt Ormonte couldn’t quite decide if he

wanted to be in on the fun or was disapproving of it, and the baritone

delivered his single aria persuasively. The choruses brought the cast

together in vigorous ensembles: ‘Viva Partenope!’ was a persuasive choric

salute.

Music director Bertie Baigent directed a 13-strong instrumental ensemble

playing on period instruments and tuned at Baroque pitch. The French

overture is one of stature, and there are several orchestral sinfonias

which the young musicians performed with confidence once the tuning had

settled down after a slightly ropey start. The long thin balcony above the

stage isn’t the most accommodating space, and sometimes the separation of

the obbligato woodwind (standing behind Baigent) from the body of strings

did not aid ensemble and intonation, but there was plenty of colour and

energy.

Despite its general good humour and humorousness, there are serious strains

of satire and sexual tension in the opera which Pearson’s

production didn’t really tap. But, HGO’s Partenope offers – as the

Victorians would have appreciated – levity and laughter: a pleasurable

‘day-trip’ to the seaside.

Claire Seymour

Partenope – Kali Hardwick, Rosmira – Rachael Cox, Emilio – Peter Martin,

Armindo – Erik Kallo, Ormonte – Saran Suebsantiwongse, Arsace – Hamish

McLaren; Director – Ashley Pearson, Music Director – Bertie Baigent,

Assistant Music Director and continuo – Richard Gowers, Designer – Laura

Fontana, Lighting Designer – Daniel Carter-Brennan, Fights Director –

Matthew Coulton.

Jacksons Lane Theatre, Highgate, London; Friday 17th May 2019.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Partenope%20Hardwick.jpg

image_description=http://www.operatoday.com/Partenope%20Hardwick.jpg

product=yes

product_title=Partenope: Hampstead Garden Opera

product_by=A review Claire Seymour

product_id=Above: Kali Hardwick (Partenope)

Photo credit: Laurent Compagnon