Indeed, director Pierre Audi’s production, the only one from his 1998 Ring cycle which has not been demolished, is still worth seeing or revisiting. But the publicity copy could just as easily have read “Don’t miss the first chance ever” to see Eva-Maria Westbroek sing Sieglinde on the operatic stage in her native country. Because, as she proved yet again, Westbroek is an ideal Sieglinde. The unique metal of her instrument fits the role like a glove and she portrays the downtrodden but plucky woman insightfully and with deep compassion. Her luminously intense performance was the kind that lingers in one’s memory. But the same applies to this Walküre as a whole. There was barely a cough or a wiggle as the rapt audience took it all in.

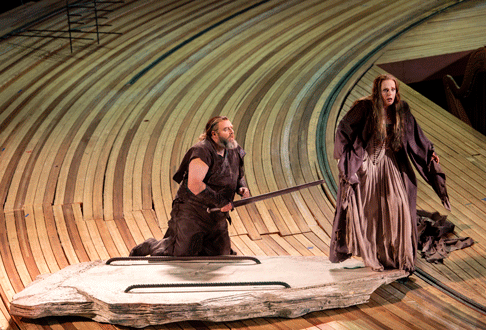

One of the strengths of this production is that, although the singers move across massive, nonspecific spaces, with the orchestra in full view, which should have an alienating effect, they always feel physically and psychologically within reach. George Tsypin’s gigantic set, which curls around the orchestra seated onstage, covers the pit and spills into the auditorium. It creates an almost conspiratorial intimacy between the singers and their public, and, with the musicians behind them, they never have to force to override the orchestra. At lofty junctures, such as Siegmund’s “Wälse!” cries and Brünnhilde’s annunciation of his death, Audi gives them heroic stature by placing them high on a rusty bridge, a construction jutting out into the hall that also serves as the ash tree growing through Hunding’s dwelling. At dramatic high points, dazzling lighting and fire effects transform the stage into an elemental battleground.

The set is not easy on the singers who have to walk up and down its steep gradient. Neither are the late Eiko Ishioka’s costumes – stiff, multilayered creations that are bona fide works of art. Alluding to several eras while avoiding the particular, they seem to be resistant to aging. The overtly aggressive Hunding, sung by orotund bass Stephen Milling, looks like a science-fictional samurai. His suffering wife Sieglinde is laced up in Medieval stays and her twin brother and lover Siegmund wears Bronze-Age tatters. The goddess Fricka, an imperiously irate Okka von der Damerau in splendid voice, uses twin ram-headed walking sticks in lieu of a ram-drawn chariot. And the Valkyries have wings that gleam like Harley-Davidsen engines. Their famous ride, as finely sung as it was choreographed, revealed another acoustic plus of the set – the whole spectrum of war goddess voices, from high to low, was distinctly audible.

The cast carried the heavy costumes with aplomb while delivering inspired performances. Tenor Michael König was a chiefly lyrical Siegmund, but with the required heroic heft. Although not the most penetrating of actors, he sang beautifully and tirelessly. Bass-baritone Iain Paterson, a master in shading text and measuring out emotion, was completely engrossing as a tyrannical Wotan. Audi’s top god in crisis is unable to keep his violent streak under control. During the clash with his wife Fricka he is disingenuous at first. Then, when he realises he is losing the argument, he makes a clumsy attempt at marital seduction. He is so emotionally crippled that he can only touch his errant favourite daughter Brünnhilde tenderly after she falls asleep. Paterson was gripping to the end, his voice quivering with emotion during Wotan’s farewell to Brünnhilde, a new role for soprano Martina Serafin. It is fair to say that her “Hojotoho!” battlecry was not the most focused, but a few stubborn top notes do not matter in such a vibrant and vocally appealing role debut. Serafin’s Valkyrie was warm of voice and temperament, a Brünnhilde to fall in love with. Next year she will sing the role at the Paris Opera in both Die Walküre and Siegfried.

Orchestrally, this was yet another riveting Wagner performance under DNO chief conductor Marc Albrecht. Amsterdam is now familiar with his supercharged, skilfully steered crescendos, and he did not disappoint when storms raged, villains gave chase and swords and spears clashed. Plying a darkish palette, the Netherlands Philharmonic burst through these passages with explosive élan, the brass bold, at times rough-edged, the strings metallized. In quieter moods, Albrecht took risks with broad tempi, sometimes paring down the sound to a mere whisper. The pay-off was a pliant performance with a steadfast sense of direction. Even when Siegmund and Sieglinde were falling in love, the music smouldered purposefully rather than flowering poetically. No wonder the audience listened with bated breath. Die Walküre runs until the 8th of December and is sold out, but same-day tickets could become available. If Siegmund’s ceaseless courage against overwhelming odds teaches us anything, it’s never say die.

Jenny Camilleri

Richard Wagner: Die Walküre

Martina Serafin, Brünnhilde; Iain Paterson, Wotan; Eva-Maria Westbroek, Sieglinde; Michael König, Siegmund; Okka von der Damerau, Fricka; Stephen Milling, Hunding; Dorothea Herbert, Gerhilde; An de Ridder, Ortlinde; Kai Rüütel, Waltraute; Julia Faylenbogen, Schwertleite; Christiane Kohl, Helmwige; Bettina Ranch, Siegrune; Eva Kroon, Grimgerde; Iris van Wijnen, Rossweisse. Pierre Audi, Director; George Tsypin, Set Designer; Eiko Ishioka, Costume Designer; Robby Duiveman, Costume Designer; Wolfgang Göbbel, Lighting Designer; Cor van den Brink, Lighting Designer; Maarten van der Put, Video. Marc Albrecht, Conductor. Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra. Seen at Dutch National Opera & Ballet, Amsterdam, on Saturday, the 16th of November, 2019.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Die-Walkure—De-Nationale-Opera-%C2%A9-Ruth-Walz-0002.png

image_description=Photo by Ruth Walz © De Nationale Opera

product=yes

product_title=Rapt audience at Dutch National Opera’s riveting Walküre

product_by=A review by Jenny Camilleri

product_id=All photos by Ruth Walz © De Nationale Opera