‘Thalberg is the first pianist in the world – Liszt is unique.’ So declared, somewhat ambiguously, the impressively named Princess Cristina Trivulzio di Belgiojoso in her Parisian salon after hearing these formidable artists in a pianistic duel – Liszt performed his Reminiscences de Robert le Diable by Meyerbeer, and Thalberg countered with his ‘Fantasy’ Op.33 based on Rossini’s Moise – which was designed as a fundraiser for Italian refugees in March 1837. This celebrated confrontation by these near contemporaries is the backstory for Hyperion’s recent compilation of operatic transcriptions and fantasies presented by the Canadian maestro Marc-André Hamelin whose copper-bottomed technique astounds throughout this generously filled disc.

Proceedings open with Liszt’s mighty Hexaméron, a twenty-minute set of variations on Bellini’s March from I puritani, which was intended for – but not completed in time – the aforementioned charity concert. A collaborativeventure, it comprises contributions by six of the foremost pianist composers of the day. Liszt assembled the variations and, in addition to providing his own, supplied an introduction and finale, as well as interludes to unite the offerings from his composer friends Thalberg, Pixis, Herz, Czerny and Chopin. Liszt’s submissions are both substantial and characterful, yet the overall sweep of the individual components is well integrated. With Hamelin’s crystalline playing you don’t have to know the original source to appreciate this bravura endeavour which is as flamboyant as the work’s title Morceau de Concert: ‘Grandes Variations de Bravoure pour piano sur la Marche des Puritains de Bellini’.

Dubbed by Liszt ‘a monster’, Hexaméron’s technical demands ensure relatively few concert appearances, so this barnstorming release is exceptionally appreciated, especially as there seems to be no limit to Hamelin’s glittering pianism. The ‘Introduction’, combining a theme by Liszt with that of Bellini, is as arresting as it is imperious, and the main theme when it appears is suitably grandiose. Hamelin’s mesmerising accuracy and athleticism is revealed in the diabolical three-handed effects of Thalberg, dispatched with boyish glee. Then there’s the impish octaves of Pixis, the quicksilver semiquavers scattered like fairy dust in the Herz variation which had me smiling from ear to ear, and the vaulting tenths and left-hand leaps demanded by Czerny. How Hamelin manages to bring such poise to the lyricism of the Chopin variation is anyone’s guess. After Liszt’s dazzling ‘Finale’ it seems almost uncharitable to observe his imagination exceeds the other contributors, evident especially in his ingenious interludes. But it’s no matter since Hamelin brings iridescent colour and unfailing sensitivity to all he touches whether strepitoso or nobilemente. Even the thunderous final chord, with the left hand an octave lower than the printed score, has heaps of chutzpah, and concludes a grandiose conception marvellously realised, nothing superficial or overstated, Hamelin’s clarity of execution peerless.

Operatic transcriptions within Liszt’s prodigious output have tended to eclipse the efforts of his Swiss-born and no less virtuosic contemporary Sigismund Thalberg whose performances, we learn from Francis Pott’s thorough liner notes, ‘were wonderfully finished and accurate, giving the impression that a wrong note was an impossibility’. Thalberg’s works, amounting to some 83 opus numbers, are peppered with ‘Grand Fantasies’ on themes drawn from numerous Italian operas. While his ‘Fantasy’ on Moses in Egypt is, arguably, longwinded, Thalberg’s trademark melodic embellishment with showers of arpeggios (delivered in the rollocking final furlong with absolute authority) in no way undermines the integrity of Rossini’s sacred drama. The composer found inspiration for several other Fantasies on tunes from Rossini operas (including Cenerentola and Il barbiere di Siviglia) and turned to Donizetti for an extensive tour d’horizon of Don Pasquale. This 1842 comic opera concerns an ageing bachelor who marries in order to disinherit his nephew Ernesto. Thalberg’s Grande fantaisie sur des motifs de ‘Don Pasquale’ provides Hamelin with further opportunities to exhibit his agility and bowling-green-smooth legato.

Liszt’s sombre yet rugged Deuxième Paraphrase de Concert on Ernani (Verdi)brings greater excitement in its tsunami of delicate arpeggios and thunderous double octaves which, in their effortless articulation, just beggar belief. Réminiscences de Norma (Bellini) is yet another work fashioned from a contemporary opera. Belonging originally to 1831, Liszt’s Reminiscences welds together themes to create a richly varied fantasy that unlocks the full armoury of a pianist’s capabilities. With a passionate commitment to this operatic traversal, Hamelin unveils (amongst other key passages) the stirring chorus ‘Dell’aura tua profetica’, Norma’s Act II aria ‘Deh! Non volerli vittime’, and crowns the whole with a rousing ‘Guerra! Guerra!’, its Presto con furia scrupulously observed and leaving nobody in any doubt as to Liszt’s remarkable achievement and Hamelin’s flawless musicianship. In short, this CD is an absolute joy and essential listening.

David Truslove

Marc-André Hamelin(piano)

Liszt etc – Hexaméron, Thalberg – Grande fantaisie sur des motifs de ‘Don Pasquale’, Liszt –Ernani, Thalberg – Fantaisie sur des thèmes de ‘Moise’, Liszt – Réminiscences de ‘Norma’.

Hyperion CDA68320 [75:00]

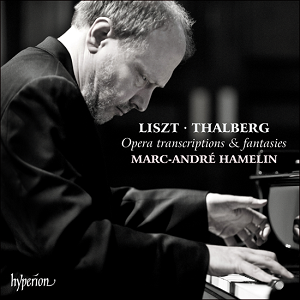

Above: Marc-André Hamelin (c) Sim Cannety-Clarke